Anointing of the sick, known also by other names such as unction, is a form of religious anointing or "unction" for the benefit of a sick person. It is practiced by many Christian churches and denominations.

The Eucharist, also known as Holy Communion, the Blessed Sacrament and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. Christians believe that the rite was instituted by Jesus at the Last Supper, the night before his crucifixion, giving his disciples bread and wine. Passages in the New Testament state that he commanded them to "do this in memory of me" while referring to the bread as "my body" and the cup of wine as "the blood of my covenant, which is poured out for many". According to the Synoptic Gospels this was at a Passover meal.

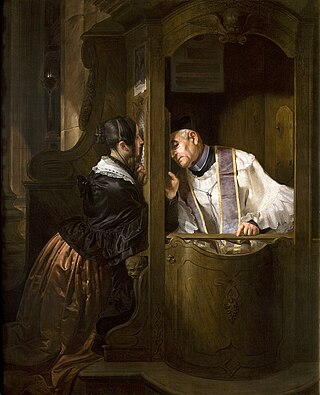

Confession, in many religions, is the acknowledgment of sinful thoughts and actions. This may occur directly to a deity or to fellow people.

Penance is any act or a set of actions done out of repentance for sins committed, as well as an alternate name for the Catholic, Lutheran, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox sacrament of Reconciliation or Confession. It also plays a part in confession among Anglicans and Methodists, in which it is a rite, as well as among other Protestants.

An Act of Contrition is a Christian prayer genre that expresses sorrow for sins. It may be used in a liturgical service or be used privately, especially in connection with an examination of conscience. Special formulae for acts of contrition are in use in the Anglican, Catholic, Lutheran, Methodist and Reformed Churches.

The epiclesis refers to the invocation of one or several gods. In ancient Greek religion, the epiclesis was the epithet used as the surname given to a deity in religious contexts. The term was borrowed into the Christian tradition, where it designates the part of the Anaphora by which the priest invokes the Holy Spirit upon the Eucharistic bread and wine in some Christian churches. In most Eastern Christian traditions, the Epiclesis comes after the Anamnesis ; in the Western Rite it usually precedes. In the historic practice of the Western Christian Churches, the consecration is effected at the Words of Institution though during the rise of the Liturgical Movement, many denominations introduced an explicit epiclesis in their liturgies.

Making the sign of the cross, also known as blessing oneself or crossing oneself, is a ritual blessing made by members of some branches of Christianity. This blessing is made by the tracing of an upright cross or Greek cross across the body with the right hand, often accompanied by spoken or mental recitation of the Trinitarian formula: "In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen."

The real presence of Christ in the Eucharist is the Christian doctrine that Jesus Christ is present in the Eucharist, not merely symbolically or metaphorically, but in a true, real and substantial way.

Consecration is the transfer of a person or a thing to the sacred sphere for a special purpose or service. The word consecration literally means "association with the sacred". Persons, places, or things can be consecrated, and the term is used in various ways by different groups. The origin of the word comes from the Latin stem consecrat, which means dedicated, devoted, and sacred. A synonym for consecration is sanctification; its antonym is desecration.

Absolution is a theological term for the forgiveness imparted by ordained Christian priests and experienced by Christian penitents. It is a universal feature of the historic churches of Christendom, although the theology and the practice of absolution vary between Christian denominations.

Eucharistic discipline is the term applied to the regulations and practices associated with an individual preparing for the reception of the Eucharist. Different Christian traditions require varying degrees of preparation, which may include a period of fasting, prayer, repentance, and confession.

Eucharistic theology is a branch of Christian theology which treats doctrines concerning the Holy Eucharist, also commonly known as the Lord's Supper and Holy Communion. It exists exclusively in Christianity, as others generally do not contain a Eucharistic ceremony.

The Prayer of Humble Access is the name traditionally given to a prayer originally from early Anglican Books of Common Prayer and contained in many Anglican, Methodist, Presbyterian, and other Christian eucharistic liturgies, including use by the personal ordinariates for former Anglican groups reconciled to the Catholic Church. Its origins lie in the healing the centurion's servant as recounted in two of the Gospels. It is comparable to the "Domine, non sum dignus" used in the Catholic Mass.

The Divine Service is a title given to the Eucharistic liturgy as used in the various Lutheran churches. It has its roots in the Pre-Tridentine Mass as revised by Martin Luther in his Formula missae of 1523 and his Deutsche Messe of 1526. It was further developed through the Kirchenordnungen of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries that followed in Luther's tradition.

The Collect for Purity is the name traditionally given to the collect prayed near the beginning of the Eucharist in most Anglican rites. Its oldest known sources are Continental, where it appears in Latin in the 10th century Sacramentarium Fuldense Saeculi X.

Thanksgiving after Communion is a spiritual practice among Christians who believe in the Real Presence of Jesus Christ in the Communion bread, maintaining themselves in prayer for some time to thank God and especially listening in their hearts for guidance from their Divine guest. This practice was and is highly recommended by saints, theologians, and Doctors of the Church.

In Lutheranism, the Eucharist refers to the liturgical commemoration of the Last Supper. Lutherans believe in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, affirming the doctrine of sacramental union, "in which the body and blood of Christ are truly and substantially present, offered, and received with the bread and wine."

A sacrament is a Christian rite that is recognized as being particularly important and significant. There are various views on the existence, number and meaning of such rites. Many Christians consider the sacraments to be a visible symbol of the reality of God, as well as a channel for God's grace. Many denominations, including the Roman Catholic, Lutheran, Presbyterian, Anglican, Methodist, and Reformed, hold to the definition of sacrament formulated by Augustine of Hippo: an outward sign of an inward grace, that has been instituted by Jesus Christ. Sacraments signify God's grace in a way that is outwardly observable to the participant.

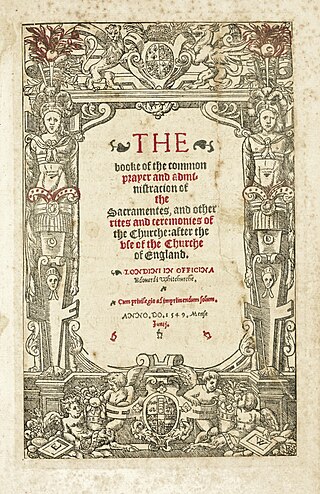

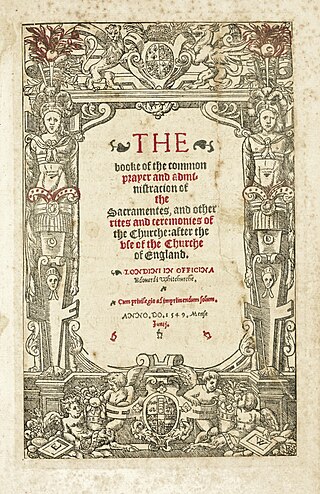

The 1549 Book of Common Prayer (BCP) is the original version of the Book of Common Prayer, variations of which are still in use as the official liturgical book of the Church of England and other Anglican churches. Written during the English Reformation, the prayer book was largely the work of Thomas Cranmer, who borrowed from a large number of other sources. Evidence of Cranmer's Protestant theology can be seen throughout the book; however, the services maintain the traditional forms and sacramental language inherited from medieval Catholic liturgies. Criticised by Protestants for being too traditional, it was replaced by the significantly revised 1552 Book of Common Prayer.

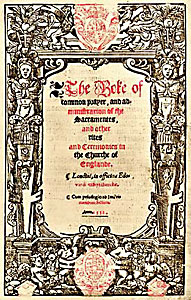

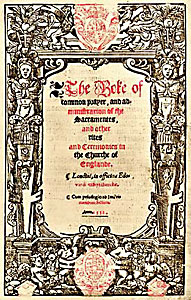

The 1552 Book of Common Prayer, also called the Second Prayer Book of Edward VI, was the second version of the Book of Common Prayer (BCP) and contained the official liturgy of the Church of England from November 1552 until July 1553. The first Book of Common Prayer was issued in 1549 as part of the English Reformation, but Protestants criticised it for being too similar to traditional Roman Catholic services. The 1552 prayer book was revised to be explicitly Reformed in its theology.