In Norse mythology, Freyja is a goddess associated with love, beauty, fertility, sex, war, gold, and seiðr. Freyja is the owner of the necklace Brísingamen, rides a chariot pulled by two cats, is accompanied by the boar Hildisvíni, and possesses a cloak of falcon feathers. By her husband Óðr, she is the mother of two daughters, Hnoss and Gersemi. Along with her twin brother Freyr, her father Njörðr, and her mother, she is a member of the Vanir. Stemming from Old Norse Freyja, modern forms of the name include Freya, Freyia, and Freja.

In Norse mythology, Heimdall is a god. He is the son of Odin and nine mothers. Heimdall keeps watch for invaders and the onset of Ragnarök from his dwelling Himinbjörg, where the burning rainbow bridge Bifröst meets the sky. He is attested as possessing foreknowledge and keen senses, particularly eyesight and hearing. The god and his possessions are described in enigmatic manners. For example, Heimdall is golden-toothed, "the head is called his sword," and he is "the whitest of the gods."

Loki is a god in Norse mythology. He is the son of Fárbauti and Laufey, and the brother of Helblindi and Býleistr. Loki is married to the goddess Sigyn and they have two sons, Narfi or Nari and Váli. By the jötunn Angrboða, Loki is the father of Hel, the wolf Fenrir and the world serpent Jörmungandr. In the form of a mare, Loki was impregnated by the stallion Svaðilfari and gave birth to the eight-legged horse Sleipnir.

In Norse mythology, Njörðr is a god among the Vanir. Njörðr, father of the deities Freyr and Freyja by his unnamed sister, was in an ill-fated marriage with the goddess Skaði, lives in Nóatún and is associated with the sea, seafaring, wind, fishing, wealth, and crop fertility.

In Norse mythology, Eir is a goddess or valkyrie associated with medical skill. Eir is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources; the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson; and in skaldic poetry, including a runic inscription from Bergen, Norway from around 1300. Scholars have theorized about whether these three sources refer to the same figure, and debate whether Eir may have been originally a healing goddess or a valkyrie. In addition, Eir has been compared to the Greek goddess Hygieia.

In Norse mythology, Vár or Vór is a goddess associated with oaths and agreements. Vár is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources; the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson; and kennings found in skaldic poetry and a runic inscription. Scholars have proposed theories about the implications of the goddess.

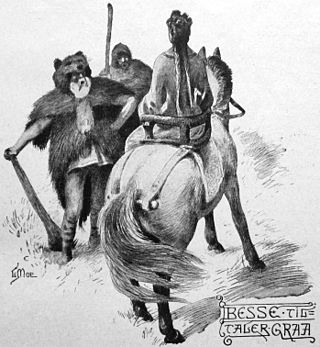

Dagr is the divine personification of the day in Norse mythology. He appears in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. In both sources, Dagr is stated to be the son of the god Dellingr and is associated with the bright-maned horse Skinfaxi, who "draw[s] day to mankind". Depending on manuscript variation, the Prose Edda adds that Dagr is either Dellingr's son by Nótt, the personified night, or Jörð, the personified Earth. Otherwise, Dagr appears as a common noun simply meaning "day" throughout Old Norse works. Connections have been proposed between Dagr and other similarly named figures in Germanic mythology.

In Norse mythology, Fólkvangr is a meadow or field ruled over by the goddess Freyja where half of those that die in combat go upon death, whilst the other half go to the god Odin in Valhalla. Others were also brought to Fólkvangr after their death; Egils Saga, for example, has a world-weary female character declare that she will never taste food again until she dines with Freyja. Fólkvangr is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. According to the Prose Edda, within Fólkvangr is Freyja's hall Sessrúmnir. Scholarly theories have been proposed about the implications of the location.

In Norse mythology, Fensalir is a location where the goddess Frigg dwells. Fensalir is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. Scholars have proposed theories about the implications of the location, including that the location may have some connection to religious practices involving springs, bogs, or swamps in Norse paganism, and that it may be connected to the goddess Sága's watery location Sökkvabekkr.

Gullveig is a female figure in Norse mythology associated with the legendary conflict between the Æsir and Vanir. In the poem Völuspá, she came to the hall of Odin (Hár) where she is speared by the Æsir, burnt three times, and yet thrice reborn. Upon her third rebirth, she began practicing seiðr and took the name Heiðr.

In Norse mythology, Sinmara is a gýgr (giantess), usually considered a consort to the fiery jötunn Surtr, the lord of Muspelheim, but wife of Mimir. Sinmara is attested solely in the poem Fjölsvinnsmál, where she is mentioned alongside Surtr in one (emended) stanza, and described as keeper of the legendary weapon Lævateinn in a later passage. Assorted theories have been proposed about the etymology of her name, and her connection with other figures in Norse mythology.

In Norse mythology, Gastropnir was in the realm of Menglöð.

Svipdagsmál is an Old Norse poem, sometimes included in modern editions of the Poetic Edda, comprising two poems, The Spell of Gróa and The Lay of Fjölsviðr.

Grógaldr or The Spell of Gróa is the first of two Old Norse poems, now commonly published under the title Svipdagsmál found in several 17th-century paper manuscripts with Fjölsvinnsmál. In at least three of these manuscripts, the poems are in reverse order and separated by a third eddic poem titled, Hyndluljóð. For a long time, the connection between the two poems was not realized, until in 1854 Svend Grundtvig pointed out a connection between the story told in Gróagaldr and the first part of the medieval Scandinavian ballad of Ungen Sveidal/Herr Svedendal/Hertig Silfverdal. Then in 1856, Sophus Bugge noticed that the last part of the ballad corresponded to Fjölsvinnsmál. Bugge wrote about this connection in Forhandlinger i Videnskabs-Selskabet i Christiania 1860, calling the two poems together Svipdagsmál. Subsequent scholars have accepted this title.

In Norse mythology, Gróa is a völva (seeress) and practitioner of seiðr. She is the wife of Aurvandil the Bold. Groa was also the goddess of knowledge.

Fjölsvinnsmál is the second of two Old Norse poems commonly published under the title Svipdagsmál "The Lay of Svipdagr". These poems are found together in several 17th-century paper manuscripts with Fjölsvinnsmál. In at least three of these manuscripts, the poems appear in reverse order and are separated by a third eddic poem titled Hyndluljóð. For a long time, the connection between the two poems was not realized, until in 1854 Svend Grundtvig pointed out a connection between the story told in Gróagaldr and the first part of the medieval Scandinavian ballad of Ungen Sveidal/Herr Svedendal/Hertig Silfverdal. Then in 1856, Sophus Bugge noticed that the last part of the ballad corresponded to Fjölsvinnsmál. Bugge wrote about this connection in Forhandlinger i Videnskabs-Selskabet i Christiania 1860, calling the two poems together Svipdagsmál. Subsequent scholars have accepted this title.

In Norse mythology, Sága is a goddess associated with the location Sökkvabekkr. At Sökkvabekkr, Sága and the god Odin merrily drink as cool waves flow. Both Sága and Sökkvabekkr are attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and in the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. Scholars have proposed theories about the implications of the goddess and her associated location, including that the location may be connected to the goddess Frigg's fen residence Fensalir and that Sága may be another name for Frigg.

In Norse mythology, Mímameiðr is a tree whose branches stretch over every land, is unharmed by fire or metal, bears fruit that assists pregnant women, and upon whose highest bough roosts the cock Víðópnir. Mímameiðr is solely attested in the Old Norse poem Fjölsvinnsmál. Due to parallels between descriptions of the two, scholars generally consider Mímameiðr to be another name for the world tree Yggdrasil, along with the similarly named Hoddmímis holt, a wood within which Líf and Lífthrasir are foretold to take refuge during the events of Ragnarök. Mímameiðr is sometimes modernly anglicized as Mimameid or Mimameith.

In Norse mythology, Svafrþorinn is the father of Menglöð by an unnamed mother, and is attested solely in a stanza of Fjölsvinnsmál. As this is the only mention of the figure, further information has been theorized from the potential etymologies of the name Svafrþorinn and his relation to Menglöð.

In Norse mythology, Gefjon is a goddess associated with ploughing, the Danish island of Zealand, the legendary Swedish king Gylfi, the legendary Danish king Skjöldr, foreknowledge, her oxen children, and virginity. Gefjon is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources; the Prose Edda and Heimskringla, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson; in the works of skalds; and appears as a gloss for various Greco-Roman goddesses in some Old Norse translations of Latin works.