Týr is a god in Germanic mythology and member of the Æsir. In Norse mythology, which provides most of the surviving narratives about gods among the Germanic peoples, Týr sacrifices his right hand to the monstrous wolf Fenrir, who bites it off when he realizes the gods have bound him. Týr is foretold of being consumed by the similarly monstrous dog Garmr during the events of Ragnarök.

Yggdrasil is an immense and central sacred tree in Norse cosmology. Around it exists all else, including the Nine Worlds.

In Norse mythology, Óðr or Óð, sometimes anglicized as Odr or Od, is a figure associated with the major goddess Freyja. The Prose Edda and Heimskringla, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson, both describe Óðr as Freyja's husband and father of her daughter Hnoss. Heimskringla adds that the couple produced another daughter, Gersemi. A number of theories have been proposed about Óðr, generally that he is a hypostasis of the deity Odin due to their similarities.

Germanic mythology consists of the body of myths native to the Germanic peoples, including Norse mythology, Anglo-Saxon mythology, and Continental Germanic mythology. It was a key element of Germanic paganism.

In Germanic paganism, a seeress is a woman said to have the ability to foretell future events and perform sorcery. They are also referred to with many other names meaning "prophetess", "staff bearer" and "sorceress", and they are frequently called witches both in early sources and in modern scholarship. In Norse mythology the seeress is usually referred to as völva or vala.

An Irminsul was a sacred, pillar-like object attested as playing an important role in the Germanic paganism of the Saxons. Medieval sources describe how an Irminsul was destroyed by Charlemagne during the Saxon Wars. A church was erected on its place in 783 and blessed by Pope Leo III. Sacred trees and sacred groves were widely venerated by the Germanic peoples, and the oldest chronicle describing an Irminsul refers to it as a tree trunk erected in the open air.

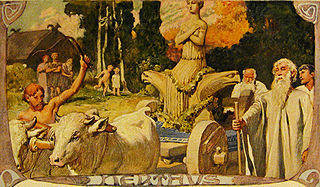

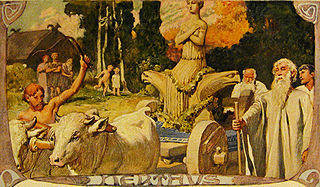

In Germanic paganism, Nerthus is a goddess associated with a ceremonial wagon procession. Nerthus is attested by first century A.D. Roman historian Tacitus in his ethnographic work Germania as a "Mother Earth".

Old Norse religion, also known as Norse paganism, is a branch of Germanic religion which developed during the Proto-Norse period, when the North Germanic peoples separated into a distinct branch of the Germanic peoples. It was replaced by Christianity and forgotten during the Christianisation of Scandinavia. Scholars reconstruct aspects of North Germanic Religion by historical linguistics, archaeology, toponymy, and records left by North Germanic peoples, such as runic inscriptions in the Younger Futhark, a distinctly North Germanic extension of the runic alphabet. Numerous Old Norse works dated to the 13th-century record Norse mythology, a component of North Germanic religion.

Germanic paganism or Germanic religion refers to the traditional, culturally significant religion of the Germanic peoples. With a chronological range of at least one thousand years in an area covering Scandinavia, the British Isles, modern Germany, the Netherlands, and at times other parts of Europe, the beliefs and practices of Germanic paganism varied. Scholars typically assume some degree of continuity between Roman-era beliefs and those found in Norse paganism, as well as between Germanic religion and reconstructed Indo-European religion and post-conversion folklore, though the precise degree and details of this continuity are subjects of debate. Germanic religion was influenced by neighboring cultures, including that of the Celts, the Romans, and, later, by the Christian religion. Very few sources exist that were written by pagan adherents themselves; instead, most were written by outsiders and can thus present problems for reconstructing authentic Germanic beliefs and practices.

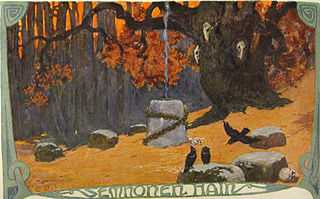

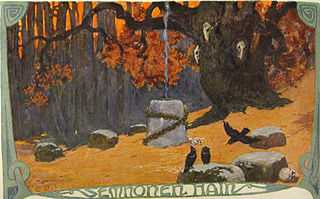

In Tacitus' work Germania from the year 98, regnator omnium deus was a deity worshipped by the Semnones tribe in a sacred grove. Comparisons have been made between this reference and the poem Helgakviða Hundingsbana II, recorded in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources.

The Alcis or Alci were a pair of divine young brothers worshipped by the Naharvali, an ancient Germanic tribe from Central Europe. The Alcis are solely attested by Roman historian and senator Tacitus in his ethnography Germania, written around 98 AD.

A grove of Fetters is mentioned in the Eddic poem "Helgakviða Hundingsbana II":

In Germanic paganism, Tamfana is a goddess. The destruction of a temple dedicated to the goddess is recorded by Roman senator Tacitus to have occurred during a massacre of the Germanic Marsi by forces led by Roman general Germanicus. Scholars have analyzed the name of the goddess and have advanced theories regarding her role in Germanic paganism.

Odin is a widely revered god in Germanic paganism. Norse mythology, the source of most surviving information about him, associates him with wisdom, healing, death, royalty, the gallows, knowledge, war, battle, victory, sorcery, poetry, frenzy, and the runic alphabet, and depicts him as the husband of the goddess Frigg. In wider Germanic mythology and paganism, the god was also known in Old English as Wōden, in Old Saxon as Uuôden, in Old Dutch as Wuodan, in Old Frisian as Wêda, and in Old High German as Wuotan, all ultimately stemming from the Proto-Germanic theonym *Wōðanaz, meaning 'lord of frenzy', or 'leader of the possessed'.

In Germanic paganism, Baduhenna is a goddess. Baduhenna is solely attested in Tacitus's Annals where Tacitus records that a sacred grove in ancient Frisia was dedicated to her, and that near this grove 900 Roman soldiers were killed in 28 CE. Scholars have analyzed the name of the goddess and linked the figure to the Germanic Matres and Matronae.

In Germanic paganism, a vé or wēoh is a type of shrine, sacred enclosure or other place with religious significance. The term appears in skaldic poetry and in place names in Scandinavia, often in connection with an Old Norse deity or a geographic feature.

Ganna was a Germanic seeress, of the Semnoni tribe, who succeeded the seeress Veleda as the leader of a Germanic alliance in rebellion against the Roman Empire. She went together with her king Masyus as envoys to Rome to discuss with Roman emperor Domitian himself, and was received with honours, after which she returned home. She is only mentioned by name in the works of Cassius Dio, but she also appears to have provided posterity with select information about the religious practices and the mythology of the early Germanic tribes, through the contemporary Roman historian Tacitus who wrote them down in Germania. Her name may be a reference to her priestly insignia, the wand, or to her spiritual abilities, and she probably taught her craft to Waluburg who would serve as a seeress in Roman Egypt at the First Cataract of the Nile.

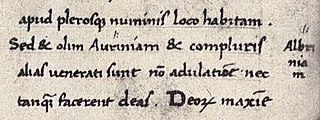

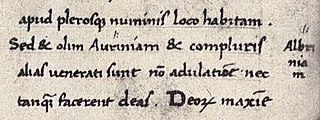

Albruna, Aurinia or Albrinia are some of the forms of the name of a probable Germanic seeress who would have lived in the late 1st century BC or in the early 1st century AD. She was mentioned by Tacitus in Germania, after the seeress Veleda, and he implied that the two were venerated because of true divine inspiration by the Germanic peoples, in contrast to Roman women who were fabricated into goddesses. It has also been suggested that she was the frightening giant woman who addressed the Roman general Drusus in his own language and made him turn back at the Elbe, only to die shortly after, but this may also be an invention to explain why a consul of Rome would have turned back. In addition, there is so little evidence for her that not every scholar agrees that she was a seeress, or that she should be included in a discussion on them. She may also have been a minor goddess, a matron.

In Norse mythology, the sister-wife of Njörðr is the unnamed twin sister and wife of the god Njörðr, with whom he is described as having had the twin children Freyr and Freyja. This shadowy goddess is attested to in the Poetic Edda poem Lokasenna, recorded in the 13th century by an unknown source, and the Heimskringla book Ynglinga saga, a euhemerized account of the Norse gods composed by Snorri Sturluson also in the 13th century but based on earlier traditional material. The figure receives no further mention in Old Norse texts.

Proto-Germanic paganism was the beliefs of the speakers of Proto-Germanic and includes topics such as the Germanic mythology, legendry, and folk beliefs of early Germanic culture. By way of the comparative method, Germanic philologists, a variety of historical linguist, have proposed reconstructions of entities, locations, and concepts with various levels of security in early Germanic folklore. The present article includes both reconstructed forms and proposed motifs from the early Germanic period.