Chakravarti RajagopalachariBR, popularly known as Rajaji or C.R., also known as Mootharignar Rajaji, was an Indian statesman, writer, lawyer, and Indian independence activist. Rajagopalachari was the last Governor-General of India, as when India became a republic in 1950 the office was abolished. He was also the only Indian-born Governor-General, as all previous holders of the post were British nationals. He also served as leader of the Indian National Congress, Premier of the Madras Presidency, Governor of West Bengal, Minister for Home Affairs of the Indian Union and Chief Minister of Madras state. Rajagopalachari founded the Swatantra Party and was one of the first recipients of India's highest civilian award, the Bharat Ratna. He vehemently opposed the use of nuclear weapons and was a proponent of world peace and disarmament. During his lifetime, he also acquired the nickname 'Mango of Salem'.

The Janata Party is an unrecognised political party in India. Navneet Chaturvedi is the current president of the party since November 2021, replacing Jaiprakash Bandhu.

Krishikar Lok Party was a political party in the Hyderabad State, India, which existed from April to June 1951. The KLP was formed when Acharya N. G. Ranga separated from the Hyderabad State Praja Party.

Krishna Nehru Hutheesing was an Indian writer, the youngest sister of Jawaharlal Nehru and Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, and part of the Nehru-Gandhi family.

Bharatiya Lok Dal was a political party in India. The BLD or simply BL was formed at the end of 1974 through the fusion of seven parties opposed to the rule of Indira Gandhi, including the Swatantra Party, the Samyukta Socialist Party, the Utkal Congress and the Bharatiya Kranti Dal. The leader of the BLD was Charan Singh.

Gopalkrishna Devadas Gandhi is a former administrator and diplomat who served as the 22nd Governor of West Bengal serving from 2004 to 2009. He is the grandson of Mahatma Gandhi and C. Rajagopalachari (Rajaji). As a former IAS officer he served as Secretary to the President of India and as High Commissioner to South Africa and Sri Lanka, among other administrative and diplomatic posts. He was the United Progressive Alliance nominee for Vice President of India 2017 elections and lost with 244 votes against NDA candidate Venkaiah Naidu, who got 516 votes.

The history of independent India or history of Republic of India began when the country became an independent sovereign state within the British Commonwealth on 15 August 1947. Direct administration by the British, which began in 1858, affected a political and economic unification of the subcontinent. When British rule came to an end in 1947, the subcontinent was partitioned along religious lines into two separate countries—India, with a majority of Hindus, and Pakistan, with a majority of Muslims. Concurrently the Muslim-majority northwest and east of British India was separated into the Dominion of Pakistan, by the Partition of India. The partition led to a population transfer of more than 10 million people between India and Pakistan and the death of about one million people. Indian National Congress leader Jawaharlal Nehru became the first Prime Minister of India, but the leader most associated with the independence struggle, Mahatma Gandhi, accepted no office. The constitution adopted in 1950 made India a democratic republic with Westminster style parliamentary system of government, both at federal and state level respectively. The democracy has been sustained since then. India's sustained democratic freedoms are unique among the world's newly independent states.

Sardar Gouthu Latchanna was an Indian politician, statesman and freedom fighter from India.

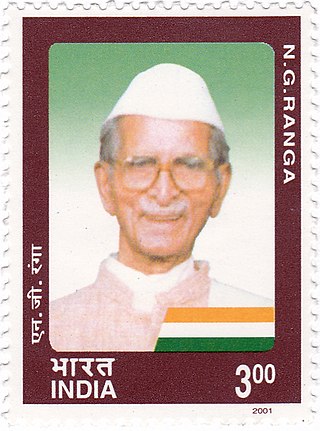

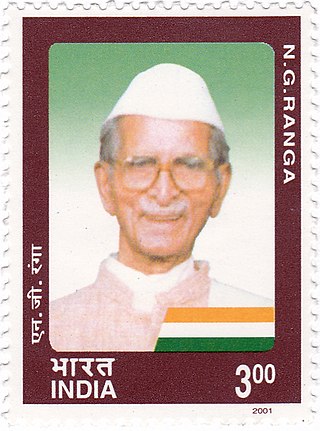

AcharyaGogineni Ranga Nayukulu, also known as N. G. Ranga, was an Indian freedom fighter, classical liberal, parliamentarian and farmers' leader. He was the founding president of the Swatantra Party, and an exponent of the peasant philosophy. He received the Padma Vibhushan award for his contributions to the Peasant Movement. N.G. Ranga served in the Indian Parliament for six decades, from 1930 to 1991.

Minocher Rustom "Minoo" Masani was an Indian politician, a leading figure of the erstwhile Swatantra Party. He was a three-time Member of Parliament, representing Gujarat's Rajkot constituency in the second, third and fourth Lok Sabha. A Parsi, he was among the founders of the Indian Liberal Group think tank that promoted classical liberalism.

Piloo Mody was an Indian architect and politician and one of the founding members of the Swatantra Party. Elected to the 4th and 5th Lok Sabhas, he served in the Rajya Sabha from 1978 until his death.

General elections were held in India between 17 and 21 February 1967 to elect 520 of the 523 members of the fourth Lok Sabha, an increase of 15 from the previous session of Lok Sabha. Elections to State Assemblies were also held simultaneously, the last general election to do so.

Godhra was a Lok Sabha parliamentary constituency in Gujarat, India. Most of its area is now covered by the Panchmahal Lok Sabha constituency, after the 2008 delimitation.

Kumaraswami Kamaraj, popularly known as Kamarajar was an Indian independence activist and politician who served as the Chief Minister of Madras from 13 April 1954 to 2 October 1963. He also served as the president of the Indian National Congress between 1964–1967 and was responsible for the elevation of Lal Bahadur Shastri and later Indira Gandhi to the position of Prime Minister of India, because of which he was widely acknowledged as the "Kingmaker" in Indian politics during the 1960s. Later, he was the founder and president of the Indian National Congress (O).

Chakravarti Rajagopalachari Narasimhan (1909–1989) was an Indian politician, freedom-fighter and member of the Indian Parliament from 1952 to 1962. He was the son of Indian statesman Chakravarti Rajagopalachari.

Balakrishna Venkanna Nayak M.P. (1929–2008) was known to the people of Karnataka by his nickname, Balasaheb. He was elected from the Karwar District Constituency in 1971 to Loka Sabha, of the Parliament of India.

The 1967 Indian general election polls in Tamil Nadu were held for 39 seats in the state. The result was a huge victory for Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, led by C.N. Annadurai and its ally Swatantra Party, led by C. Rajagopalachari. Madras was the first and one of few states, where a non-Congress Party won more seats than Congress in a state. A huge wave of anti-incumbency against the Congress was present in Madras, 1967, which led to the defeat of the popular leader K. Kamaraj and his party in both the state and national elections, won by DMK and its allies. After this election, the DMK supported the Congress party under Indira Gandhi.

Mariadas Ruthnaswamy CIE, KCSG (1885–1977) was a leading educationalist, statesman and a writer in Madras, India.

Singanallur Venkatraman Raju was an Indian politician, best known for his association with the Swatantra Party on post of executive secretary of the party and his editorship of Freedom First magazine.

The 1971 Indian general election in Odisha were held for 20 seats with the state going to the polls in the first two phases of the general elections.