Hopi is a Uto-Aztecan language spoken by the Hopi people of northeastern Arizona, United States.

Crow is a Missouri Valley Siouan language spoken primarily by the Crow Nation in present-day southeastern Montana. The word, Apsáalooke, translates to "children of the raven." It is one of the larger populations of American Indian languages with 2,480 speakers according to the 1990 US Census.

The Muscogee language, previously referred to by its exonym, Creek, is a Muskogean language spoken by Muscogee (Creek) and Seminole people, primarily in the US states of Oklahoma and Florida. Along with Mikasuki, when it is spoken by the Seminole, it is known as Seminole.

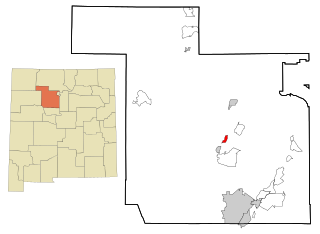

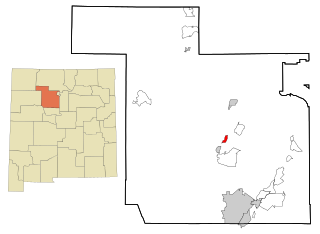

Keres, also Keresan, is a Native American language, spoken by the Keres Pueblo people in New Mexico. Depending on the analysis, Keres is considered a small language family or a language isolate with several dialects. The varieties of each of the seven Keres pueblos are mutually intelligible with its closest neighbors. There are significant differences between the Western and Eastern groups, which are sometimes counted as separate languages.

Supyire, or Suppire, is a Senufo language spoken in the Sikasso Region of southeastern Mali and in adjoining regions of Ivory Coast. In their native language, the noun sùpyìré means both "the people" and "the language spoken by the people".

Kiowa or Cáuijògà/Cáuijò꞉gyà is a Tanoan language spoken by the Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma in primarily Caddo, Kiowa, and Comanche counties. The Kiowa tribal center is located in Carnegie. Like most North American indigenous languages, Kiowa is an endangered language.

The Wariʼ language is the sole remaining vibrant language of the Chapacuran language family of the Brazilian–Bolivian border region of the Amazon. It has about 2,700 speakers, also called Wariʼ, who live along tributaries of the Pacaas Novos river in Western Brazil. The word wariʼ means "we!" in the Wariʼ language and is the term given to the language and tribe by its speakers.

Tooro or Rutooro is a Bantu language spoken mainly by the Tooro people (Abatooro) from the Tooro Kingdom in western Uganda. There are three main areas where Tooro as a language is mainly used: Kabarole District, Kyenjojo District and Kyegegwa District. Tooro is unique among Bantu languages as it lacks lexical tone. It is most closely related to Runyoro.

The Yimas language is spoken by the Yimas people, who populate the Sepik River Basin region of Papua New Guinea. It is spoken primarily in Yimas village, Karawari Rural LLG, East Sepik Province. It is a member of the Lower-Sepik language family. All 250-300 speakers of Yimas live in two villages along the lower reaches of the Arafundi River, which stems from a tributary of the Sepik River known as the Karawari River.

Ixcatec is a language spoken by the people of the Mexican village of Santa María Ixcatlan, in the northern part of the state of Oaxaca. The Ixcatec language belongs to the Popolocan branch of the Oto-manguean language family. It is believed to have been the second language to branch off from the others within the Popolocan subgroup, though there is a small debate over the relation it has to them.

The Nukak language is a language of uncertain classification, perhaps part of the macrofamily Puinave-Maku. It is very closely related to Kakwa.

Taos is a Tanoan language spoken by several hundred people in New Mexico, in the United States. The main description of its phonology was contributed by George L. Trager in a (pre-generative) structuralist framework. Earlier considerations of the phonetics-phonology were by John P. Harrington and Jaime de Angulo. Trager's first account was in Trager (1946) based on fieldwork 1935-1937, which was then substantially revised in Trager (1948). The description below takes Trager (1946) as the main point of departure and notes where this differs from the analysis of Trager (1948). Harrington's description is more similar to Trager (1946). Certain comments from a generative perspective are noted in a comparative work Hale (1967).

Jemez is a Tanoan language spoken by the Jemez Pueblo people in New Mexico. It has no common written form, as tribal rules do not allow the language to be transcribed; linguists describing the language use the Americanist phonetic notation.

Lau (Law) is a Jukunoid language of Lau LGA, Taraba State, Nigeria. Lau speakers claim that their language is mutually intelligible with the Jukunoid language varieties spoken in Kunini, Bandawa, and Jeshi. They also live alongside the Central Sudanic-speaking Laka, who live in Laka ward of Lau LGA.

The Pueblo linguistic area is a Sprachbund consisting of the languages spoken in and near North American Pueblo locations. There are also many shared cultural practices in this area. For example, these cultures share many ceremonial vocabulary terms meant for prayer or song.

Tuyuca is an Eastern Tucanoan language. Tuyuca is spoken by the Tuyuca, an indigenous ethnic group of some 500-1000 people, who inhabit the watershed of the Papuri River, the Inambú River, and the Tiquié River, in Vaupés Department, Colombia, and Amazonas State, Brazil.

Pech or Pesh is a Chibchan language spoken in Honduras. It was formerly known as Paya, and continues to be referred to in this manner by several sources, though there are negative connotations associated with this term. It has also been referred to as Seco. There are 300 speakers according to Yasugi (2007). It is spoken near the north-central coast of Honduras, in the Dulce Nombre de Culmí municipality of Olancho Department.

Ramarama, also known as Karo, is a Tupian language of Brazil.

Zoogocho Zapotec, or Diža'xon, is a Zapotec language of Oaxaca, Mexico.

Matlatzinca, or more specifically San Francisco Matlatzinca, is an endangered Oto-Manguean language of Western Central Mexico. The name of the language in the language itself is pjiekak'joo. The term "Matlatzinca" comes from the town's name in Nahuatl, meaning "the lords of the network." At one point, the Matlatzinca groups were called "pirindas," meaning "those in the middle."