BC

- c. 1600 BC – The Edwin Smith Papyrus, a unique ancient Egyptian text, contains practical and objective advice to physicians regarding the examination, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis, of injuries and ailments. [1] It provides evidence that medicine in Egypt was at this time practiced as a quantifiable science. [2]

- c. 600 – 700 BC – The earliest form of Charvaka practiced by philosopher Ajita Kesakambali. [3] [4]

- c. 600 – 200 BC – The Vaisheshika school of Hindu philosophy, founded by the ancient Indian philosopher Kanada, accepted perception and inference as the only two reliable sources of knowledge. [5]

- c. 624 – 548 BC – Thales of Miletus raises the study of nature from the realm of the mythical to the level of empirical study. [6]

- c. 610 – 547 BC – The Greek philosopher Anaximander extends the idea of law from human society to the physical world, and is the first to use maps and models. [7]

- c.400 BC – In China, the philosopher Mozi founds the Mohist school of philosophy and introduces the 'three-prong method' for testing the truth or falsehood of statements. [8]

- c.400 BC – The Greek philosopher Democritus advocates inductive reasoning through a process of examining the causes of perceptions and drawing conclusions about the outside world. [9]

- c.400 BC – Plato provides the first detailed definitions of the concepts of idea, matter, form and appearance.

- c.320 BC – Aristotle categorizes and subdivides knowledge into physics, poetry, zoology, logic, rhetoric, politics, and biology. His Posterior Analytics defended the ideal of science as originating from known axioms. Aristotle believed that the world was real and that we can learn the truth by experience. [10]

- c.341-270 BC – Epicurus and his followers develop an epistemology as a result of their rivalry with other philosophical schools. His treatise Κανών ('Rule'), now lost, explained his methods of investigation and theory of knowledge. [10] [11]

- c.300 BC – Euclid's Euclid's Elements expounds geometry as a system of theorems following logically from axioms.

- c.240 BC – The Greek polymath Eratosthenes calculates the circumference of the Earth to a remarkable degree of accuracy, using stadia, then a standard unit for measuring distances.

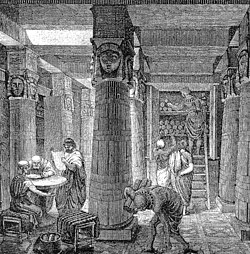

- c.200 BC – The Great Library of Alexandria is built as part of a larger research institution called the Mouseion, with the intention that it becomes a collection of all Greek knowledge. [12]

- c.150 BC – The first chapter of the Book of Daniel describes an early (and flawed) version of a clinical trial proposed by the young Jewish noble Daniel, in which he and his three companions eat vegetables and water for ten days, rather than the royal food and wine. [13]