101

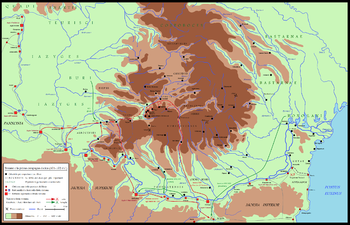

After support from the Roman Senate, by 101 Trajan was ready to advance on Dacia.

Trajan left Italy in 101 [5] and went via Ancona and Iader to head probably to Viminacium in the province of Moesia Superior.

He was accompanied by the Praetorian Guard and his praetorian prefect, Tiberius Claudius Livianus [6] as well as a whole series of comites such as Lucius Licinius Sura, Quintus Sosius Senecio, [7] Lusius Quietus, [8] Gnaeus Pompeius Longinus, [9] Hadrian (the future successor of Trajan, then 25 years old) and perhaps Decimus Terentius Scaurianus (who would later become the first governor of the province of Dacia).

The general strategic plan of the campaign come from the words of Trajan himself: "inde Berzobim, deinde Aizi processimus" (We then advanced to Berzobim, next to Aizi). [10] These two locations were along the westernmost of the roads leading to Dacia which, starting from Viminacium on the Danube near Lederata, led to Tibiscum and then to Tapae and the pass of the so-called Iron Gates (near the current Otelu Rosu), entering Dacia. This road had already been used by Tettius Julianus in the campaign of 88.

The Roman offensive was perhaps spearheaded by two legionary columns, a hypothesis formulated after careful analysis of Trajan's Column where, in scenes 4 and 5, two parallel pontoon bridges over the Danube are depicted, one crossed by the legionaries and the other by the praetorians. The second column from Drobeta (or possibly Dierna) would have crossed the pass known as the Keys of Teregova to reunite with the first column in Tibiscum. [11] The two bridges would constitute a natural expressive means through which the sculptor would have liked to indicate the simultaneous passage of an army divided into two different "marching columns". [12] The use of separate "columns" evidently served to divide the enemy forces at strategic points, with a tactical outflanking maneouvre which was also used during Trajan's Parthian campaign of 115, with a simultaneous advance along the Tigris and the Euphrates.

He slowly made his way into Dacia and after reaching Tibiscum apparently without having sustained any major battles, he camped there waiting to attack the Dacian forts near the mouth of the Iron Gates. Here he engaged in the fierce Third Battle of Tapae with the bulk of the army. The clash, as also illustrated on the Column, [13] was favourable to the Romans but at the cost of great bloodshed, [14] although it was not decisive since Decebalus was able to establish himself within his forts in the area of Orăștie, ready to block access to the capital Sarmizegetusa Regia. Because the winter was near, Trajan decided to wait until spring to continue his offensive.

However, during the winter of 101/102, Decebalus, now blocked in the west, decided to go on the counterattack, aiming above all to open a second front to thus divide the forces of the Roman army. As had already happened in 85, he chose to attack Moesia Inferior, together with his Sarmatian allies the Roxolani (also shown on the Column [15] ). The two armies crossed the river but, despite achieving some initial success, they were kept at bay by the then governor and skilled general, Manius Laberius Maximus, who also managed to capture the sister of the Dacian king, also illustrated the column. Trajan, mindful of the similar action that had taken place over fifteen years earlier during Domitian's Dacian campaigns, had prepared himself well for a similar strategic move by the Dacians. But only with the arrival of the reinforcements, led by Trajan himself (represented on the Column in the act of reaching the front on boats of the Danube fleet), were the Dacians and Roxolani stopped and heavily defeated, [16] perhaps separately:

102

In 102 Trajan's offensive resumed in March with an advance on multiple fronts.

The first "column" crossed the Danube perhaps at Oescus, continued along the Aluta valley until reaching the sufficiently large and accessible pass of the Red Tower. Two other columns advanced probably along the same lines followed the previous year (i.e. through the " Iron Gates " and the Teregova Keys pass). The final meeting point of the three armies was about 20 km north-west of Sarmizegetusa Regia. [20] There the Roman armies converged for an assault and defeated the Dacian army.

Decebalus, shaken by his second defeat and above all by the simultaneous advance along three fronts in a "pincer maneouvre" which saw the imperial troops take possession of numerous Dacian fortresses, increasingly closer to the capital, sent two embassies to the Roman emperor, each with a plea for peace. Trajan refused to listen to the first, but decided to receive the second, composed of numerous Dacian nobles. [21] Following the meeting, the emperor's chief of staff, Lucius Licinius Sura, was sent along with the praetorian prefect, Tiberius Claudius Livianus, to discuss the terms of the possible peace treaty. [22] The conditions offered by the Romans aimed at the unconditional surrender of Decebalus, were however very harsh considering the Dacians had not yet suffered irreparable defeats. The war, therefore, continued.

Trajan had continued his advance and recovered weapons and Roman engineers taken prisoner. Having passed the Red Tower pass before it could be blocked by the enemy, the Romans positioned themselves in the centre of the Carpathian arc, with the main objective of conquering the Dacian capital located further west. Trajan then divided the army into at least three columns, with which he began to besiege the Dacian fortresses of the Orăștie Mountains. One of these columns, led by Lusius Quietus, included Mauretanian knights among its ranks, perhaps identifiable in some tables of the Column.

The Dacian citadels, such as Costești, fell one after the other until even the last one, near present-day Muncel, was destroyed while the Dacian army that rushed in was heavily beaten. [23] The road to Sarmizegetusa Regia was now considered open and the war now won. Decebalus, to spare the capital the horrors of a useless siege, capitulated. This scene is also well depicted on the Column: the ambassadors sent by the Dacian king, once they entered Trajan's military camp (perhaps located near the city of Aquae), prostrate themselves at the feet of the Roman emperor imploring the cessation of hostilities. [24] After some additional conflicts, Trajan, worried by the upcoming cold winter, agreed a peace treaty.