The Classical Period was an era of classical music between roughly 1750 and 1820.

Figured bass is musical notation in which numerals and symbols appear above or below a bass note. The numerals and symbols indicate intervals, chords, and non-chord tones that a musician playing piano, harpsichord, organ, or lute should play in relation to the bass note. Figured bass is closely associated with basso continuo: a historically improvised accompaniment used in almost all genres of music in the Baroque period of Classical music, though rarely in modern music. Figured bass is also known as thoroughbass.

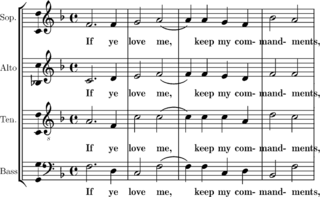

In Western classical music, a motet is mainly a vocal musical composition, of highly diverse form and style, from high medieval music to the present. The motet was one of the pre-eminent polyphonic forms of Renaissance music. According to the English musicologist Margaret Bent, "a piece of music in several parts with words" is as precise a definition of the motet as will serve from the 13th to the late 16th century and beyond. The late 13th-century theorist Johannes de Grocheo believed that the motet was "not to be celebrated in the presence of common people, because they do not notice its subtlety, nor are they delighted in hearing it, but in the presence of the educated and of those who are seeking out subtleties in the arts".

Renaissance music is traditionally understood to cover European music of the 15th and 16th centuries, later than the Renaissance era as it is understood in other disciplines. Rather than starting from the early 14th-century ars nova, the Trecento music was treated by musicology as a coda to medieval music and the new era dated from the rise of triadic harmony and the spread of the contenance angloise style from the British Isles to the Burgundian School. A convenient watershed for its end is the adoption of basso continuo at the beginning of the Baroque period.

A sackbut is an early form of the trombone used during the Renaissance and Baroque eras. A sackbut has the characteristic telescopic slide of a trombone, used to vary the length of the tube to change pitch, but is distinct from later trombones by its smaller, more cylindrically-proportioned bore, and its less-flared bell. Unlike the earlier slide trumpet from which it evolved, the sackbut possesses a U-shaped slide with two parallel sliding tubes, rather than just one.

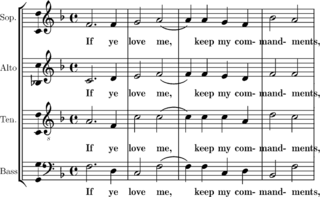

A choir, also known as a chorale or chorus is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform or in other words is the music performed by the ensemble. Choirs may perform music from the classical music repertoire, which spans from the medieval era to the present, or popular music repertoire. Most choirs are led by a conductor, who leads the performances with arm, hand, and facial gestures.

Johann Pachelbel was a German composer, organist, and teacher who brought the south German organ schools to their peak. He composed a large body of sacred and secular music, and his contributions to the development of the chorale prelude and fugue have earned him a place among the most important composers of the middle Baroque era.

In music, monophony is the simplest of musical textures, consisting of a melody, typically sung by a single singer or played by a single instrument player without accompanying harmony or chords. Many folk songs and traditional songs are monophonic. A melody is also considered to be monophonic if a group of singers sings the same melody together at the unison or with the same melody notes duplicated at the octave. If an entire melody is played by two or more instruments or sung by a choir with a fixed interval, such as a perfect fifth, it is also said to be monophony. The musical texture of a song or musical piece is determined by assessing whether varying components are used, such as an accompaniment part or polyphonic melody lines.

The theorbo is a plucked string instrument of the lute family, with an extended neck that houses the second pegbox. Like a lute, a theorbo has a curved-back sound box with a flat top, typically with one or three sound holes decorated with rosettes. As with the lute, the player plucks or strums the strings with the right hand while "fretting" the strings with the left hand.

A madrigal is a form of secular vocal music most typical of the Renaissance and early Baroque (1600–1750) periods, although revisited by some later European composers. The polyphonic madrigal is unaccompanied, and the number of voices varies from two to eight, but the form usually features three to six voices, whilst the metre of the madrigal varies between two or three tercets, followed by one or two couplets. Unlike verse-repeating strophic forms sung to the same music, most madrigals are through-composed, featuring different music for each stanza of lyrics, whereby the composer expresses the emotions contained in each line and in single words of the poem being sung.

In music, monody refers to a solo vocal style distinguished by having a single melodic line and instrumental accompaniment. Although such music is found in various cultures throughout history, the term is specifically applied to Italian song of the early 17th century, particularly the period from about 1600 to 1640. The term is used both for the style and for individual songs. The term itself is a recent invention of scholars. No composer of the 17th century ever called a piece a monody. Compositions in monodic form might be called madrigals, motets, or even concertos.

The Florentine Camerata, also known as the Camerata de' Bardi, were a group of humanists, musicians, poets and intellectuals in late Renaissance Florence who gathered under the patronage of Count Giovanni de' Bardi to discuss and guide trends in the arts, especially music and drama. They met at the house of Giovanni de' Bardi, and their gatherings had the reputation of having all the most famous men of Florence as frequent guests. After first meeting in 1573, the activity of the Camerata reached its height between 1577 and 1582. While propounding a revival of the Greek dramatic style, the Camerata's musical experiments led to the development of the stile recitativo. In this way it facilitated the composition of dramatic music and the development of opera.

Basso continuos parts, almost universal in the Baroque era (1600–1750), provided the harmonic structure of the music by supplying a bassline and a chord progression. The phrase is often shortened to continuo, and the instrumentalists playing the continuo part are called the continuo group.

Concertato is a term in early Baroque music referring to either a genre or a style of music in which groups of instruments or voices share a melody, usually in alternation, and almost always over a basso continuo. The term derives from Italian concerto which means "playing together"—hence concertato means "in the style of a concerto." In contemporary usage, the term is almost always used as an adjective, for example "three pieces from the set are in concertato style."

The Venetian polychoral style was a type of music of the late Renaissance and early Baroque eras which involved spatially separate choirs singing in alternation. It represented a major stylistic shift from the prevailing polyphonic writing of the middle Renaissance, and was one of the major stylistic developments which led directly to the formation of what is now known as the Baroque style. A commonly encountered term for the separated choirs is cori spezzati—literally, "broken choruses" as they were called, added the element of spatial contrast to Venetian music. These included the echo device, so important in the entire baroque tradition; the alternation of two contrasting bodies of sound, such as chorus against chorus, single line versus a full choir, solo voice opposing full choir, instruments pitted against voices and contrasting instrumental groups; the alternation of high and low voices; soft level of sound alternated with a loud one; the fragmentary versus the continuous; and blocked chords contrasting with flowing counterpoint.

Alessandro Grandi was a northern Italian composer of the early Baroque era, writing in the new concertato style. He was one of the most inventive, influential, and popular composers of the time, probably second only to Monteverdi in northern Italy.

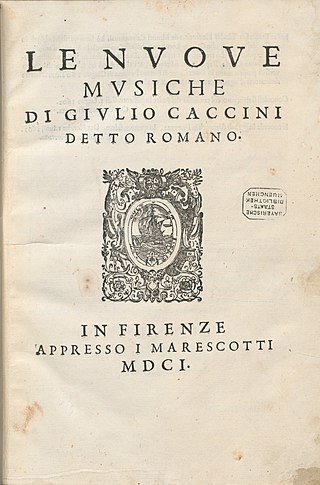

Giulio Romolo Caccini was an Italian composer, teacher, singer, instrumentalist and writer of the late Renaissance and early Baroque eras. He was one of the founders of the genre of opera, and one of the most influential creators of the new Baroque style. He was also the father of the composer Francesca Caccini and the singer Settimia Caccini.

In music, homophony is a texture in which a primary part is supported by one or more additional strands that provide the harmony. One melody predominates while the other parts play either single notes or an elaborate accompaniment. This differentiation of roles contrasts with equal-voice polyphony and monophony. Historically, homophony and its differentiated roles for parts emerged in tandem with tonality, which gave distinct harmonic functions to the soprano, bass and inner voices.

Baroque music refers to the period or dominant style of Western classical music composed from about 1600 to 1750. The Baroque style followed the Renaissance period, and was followed in turn by the Classical period after a short transition. The Baroque period is divided into three major phases: early, middle, and late. Overlapping in time, they are conventionally dated from 1580 to 1650, from 1630 to 1700, and from 1680 to 1750. Baroque music forms a major portion of the "classical music" canon, and is widely studied, performed, and listened to. The term "baroque" comes from the Portuguese word barroco, meaning "misshapen pearl". The works of Antonio Vivaldi, George Frideric Handel and Johann Sebastian Bach are considered the pinnacle of the Baroque period. Other key composers of the Baroque era include Claudio Monteverdi, Domenico Scarlatti, Alessandro Scarlatti, Alessandro Stradella, Tomaso Albinoni, Johann Pachelbel, Henry Purcell, Georg Philipp Telemann, Jean-Baptiste Lully, Jean-Philippe Rameau, Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Arcangelo Corelli, François Couperin, Johann Hermann Schein, Heinrich Schütz, Samuel Scheidt, Dieterich Buxtehude, Gaspar Sanz, José de Nebra, Antonio Soler, Carlos Seixas, Adam Jarzębski, Jan Dismas Zelenka, Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber and Giovanni Battista Pergolesi.