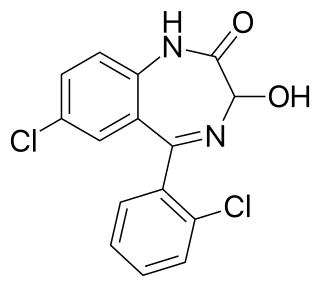

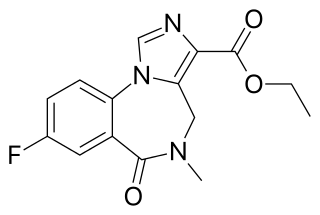

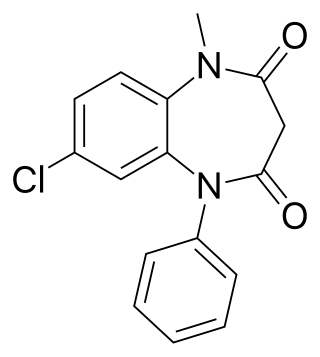

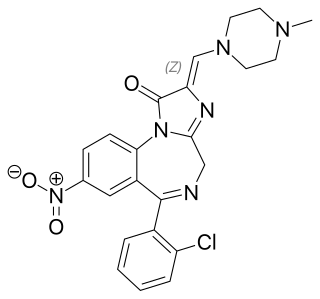

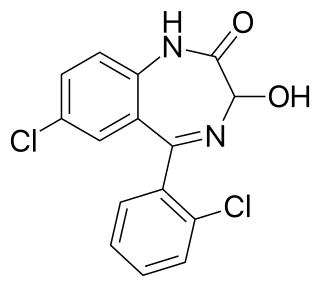

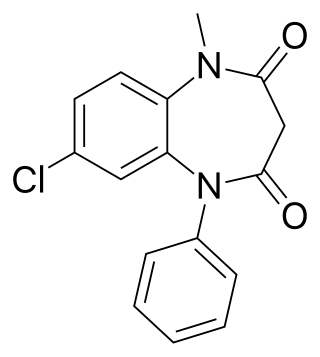

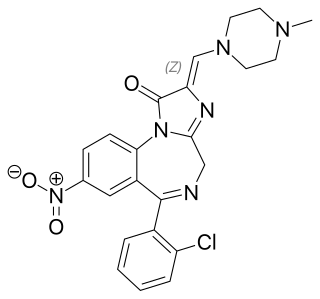

Benzodiazepines, colloquially called "benzos", are a class of depressant drugs whose core chemical structure is the fusion of a benzene ring and a diazepine ring. They are prescribed to treat conditions such as anxiety disorders, insomnia, and seizures. The first benzodiazepine, chlordiazepoxide (Librium), was discovered accidentally by Leo Sternbach in 1955, and was made available in 1960 by Hoffmann–La Roche, which followed with the development of diazepam (Valium) three years later, in 1963. By 1977, benzodiazepines were the most prescribed medications globally; the introduction of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), among other factors, decreased rates of prescription, but they remain frequently used worldwide.

Anticonvulsants are a diverse group of pharmacological agents used in the treatment of epileptic seizures. Anticonvulsants are also increasingly being used in the treatment of bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder, since many seem to act as mood stabilizers, and for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Anticonvulsants suppress the excessive rapid firing of neurons during seizures. Anticonvulsants also prevent the spread of the seizure within the brain.

Diazepam, sold under the brand name Valium among others, is a medicine of the benzodiazepine family that acts as an anxiolytic. It is used to treat a range of conditions, including anxiety, seizures, alcohol withdrawal syndrome, muscle spasms, insomnia, and restless legs syndrome. It may also be used to cause memory loss during certain medical procedures. It can be taken orally, as a suppository inserted into the rectum, intramuscularly, intravenously or used as a nasal spray. When injected intravenously, effects begin in one to five minutes and last up to an hour. When taken by mouth, effects begin after 15 to 60 minutes.

Lorazepam, sold under the brand name Ativan among others, is a benzodiazepine medication. It is used to treat anxiety, trouble sleeping, severe agitation, active seizures including status epilepticus, alcohol withdrawal, and chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. It is also used during surgery to interfere with memory formation and to sedate those who are being mechanically ventilated. It is also used, along with other treatments, for acute coronary syndrome due to cocaine use. It can be given orally, transdermal, intravenously (IV), or intramuscularly When given by injection, onset of effects is between one and thirty minutes and effects last for up to a day.

Lamotrigine, sold under the brand name Lamictal among others, is a medication used to treat epilepsy and stabilize mood in bipolar disorder. For epilepsy, this includes focal seizures, tonic-clonic seizures, and seizures in Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. In bipolar disorder, lamotrigine has not been shown to reliably treat acute depression for all groups except in the severely depressed; but for patients with bipolar disorder who are not currently symptomatic, it appears to reduce the risk of future episodes of depression.

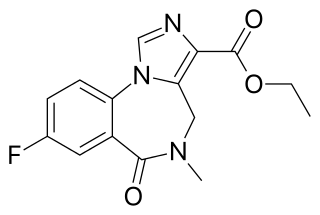

Midazolam, sold under the brand name Versed among others, is a benzodiazepine medication used for anesthesia and procedural sedation, and to treat severe agitation. It induces sleepiness, decreases anxiety, and causes anterograde amnesia.

Myoclonus is a brief, involuntary, irregular twitching of a muscle, a joint, or a group of muscles, different from clonus, which is rhythmic or regular. Myoclonus describes a medical sign and, generally, is not a diagnosis of a disease. It belongs to the hyperkinetic movement disorders, among tremor and chorea for example. These myoclonic twitches, jerks, or seizures are usually caused by sudden muscle contractions or brief lapses of contraction. The most common circumstance under which they occur is while falling asleep. Myoclonic jerks occur in healthy people and are experienced occasionally by everyone. However, when they appear with more persistence and become more widespread they can be a sign of various neurological disorders. Hiccups are a kind of myoclonic jerk specifically affecting the diaphragm. When a spasm is caused by another person it is known as a provoked spasm. Shuddering attacks in babies fall in this category.

Flumazenil is a selective GABAA receptor antagonist administered via injection, otic insertion, or intranasally. Therapeutically, it acts as both an antagonist and antidote to benzodiazepines, through competitive inhibition.

Nitrazepam, sold under the brand name Mogadon among others, is a hypnotic drug of the benzodiazepine class used for short-term relief from severe, disabling anxiety and insomnia. It also has sedative (calming) properties, as well as amnestic, anticonvulsant, and skeletal muscle relaxant effects.

Phenobarbital, also known as phenobarbitone or phenobarb, sold under the brand name Luminal among others, is a medication of the barbiturate type. It is recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) for the treatment of certain types of epilepsy in developing countries. In the developed world, it is commonly used to treat seizures in young children, while other medications are generally used in older children and adults. In developed countries it is used for veterinary purposes. It may be used intravenously, injected into a muscle, or taken by mouth. The injectable form may be used to treat status epilepticus. Phenobarbital is occasionally used to treat trouble sleeping, anxiety, and drug withdrawal and to help with surgery. It usually begins working within five minutes when used intravenously and half an hour when administered by mouth. Its effects last for between four hours and two days.

Tiagabine is an anticonvulsant medication produced by Cephalon that is used in the treatment of epilepsy. The drug is also used off-label in the treatment of anxiety disorders and panic disorder.

Status epilepticus (SE), or status seizure, is a medical condition consisting of a single seizure lasting more than 5 minutes, or 2 or more seizures within a 5-minute period without the person returning to normal between them. Previous definitions used a 30-minute time limit. The seizures can be of the tonic–clonic type, with a regular pattern of contraction and extension of the arms and legs, or of types that do not involve contractions, such as absence seizures or complex partial seizures. Status epilepticus is a life-threatening medical emergency, particularly if treatment is delayed.

Clobazam, sold under the brand names Frisium, Onfi and others, is a benzodiazepine class medication that was patented in 1968. Clobazam was first synthesized in 1966 and first published in 1969. Clobazam was originally marketed as an anxioselective anxiolytic since 1970, and an anticonvulsant since 1984. The primary drug-development goal was to provide greater anxiolytic, anti-obsessive efficacy with fewer benzodiazepine-related side effects.

Clorazepate, sold under the brand name Tranxene among others, is a benzodiazepine medication. It possesses anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, sedative, hypnotic, and skeletal muscle relaxant properties. Clorazepate is an unusually long-lasting benzodiazepine and serves as a prodrug for the equally long-lasting desmethyldiazepam, which is rapidly produced as an active metabolite. Desmethyldiazepam is responsible for most of the therapeutic effects of clorazepate.

Loprazolam (triazulenone) marketed under many brand names is a benzodiazepine medication. It possesses anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, hypnotic, sedative and skeletal muscle relaxant properties. It is licensed and marketed for the short-term treatment of moderately-severe insomnia.

Etizolam is a thienodiazepine derivative which is a benzodiazepine analog. The etizolam molecule differs from a benzodiazepine in that the benzene ring has been replaced by a thiophene ring and triazole ring has been fused, making the drug a thienotriazolodiazepine.

Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome is the cluster of signs and symptoms that may emerge when a person who has been taking benzodiazepines as prescribed develops a physical dependence on them and then reduces the dose or stops taking them without a safe taper schedule.

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) is a set of symptoms that can occur following a reduction in alcohol use after a period of excessive use. Symptoms typically include anxiety, shakiness, sweating, vomiting, fast heart rate, and a mild fever. More severe symptoms may include seizures, and delirium tremens (DTs); which can be fatal in untreated patients. Symptoms start at around 6 hours after last drink. Peak incidence of seizures occurs at 24-36 hours and peak incidence of delirium tremens is at 48-72 hours.

A convulsant is a drug which induces convulsions and/or epileptic seizures, the opposite of an anticonvulsant. These drugs generally act as stimulants at low doses, but are not used for this purpose due to the risk of convulsions and consequent excitotoxicity. Most convulsants are antagonists at either the GABAA or glycine receptors, or ionotropic glutamate receptor agonists. Many other drugs may cause convulsions as a side effect at high doses but only drugs whose primary action is to cause convulsions are known as convulsants. Nerve agents such as sarin, which were developed as chemical weapons, produce convulsions as a major part of their toxidrome, but also produce a number of other effects in the body and are usually classified separately. Dieldrin which was developed as an insecticide blocks chloride influx into the neurons causing hyperexcitability of the CNS and convulsions. The Irwin observation test and other studies that record clinical signs are used to test the potential for a drug to induce convulsions. Camphor, and other terpenes given to children with colds can act as convulsants in children who have had febrile seizures.

Benzodiazepine dependence defines a situation in which one has developed one or more of either tolerance, withdrawal symptoms, drug seeking behaviors, such as continued use despite harmful effects, and maladaptive pattern of substance use, according to the DSM-IV. In the case of benzodiazepine dependence, the continued use seems to be typically associated with the avoidance of unpleasant withdrawal reaction rather than with the pleasurable effects of the drug. Benzodiazepine dependence develops with long-term use, even at low therapeutic doses, often without the described drug seeking behavior and tolerance.