The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), whose members are nicknamed "Wobblies", is an international labor union founded in Chicago in 1905. The nickname's origin is uncertain. Its ideology combines general unionism with industrial unionism, as it is a general union, subdivided between the various industries which employ its members. The philosophy and tactics of the IWW are described as "revolutionary industrial unionism", with ties to socialist, syndicalist, and anarchist labor movements.

The Western Federation of Miners (WFM) was a labor union that gained a reputation for militancy in the mines of the western United States and British Columbia. Its efforts to organize both hard rock miners and smelter workers brought it into sharp conflicts – and often pitched battles – with both employers and governmental authorities. One of the most dramatic of these struggles occurred in the Cripple Creek district of Colorado in 1903–1904; the conflicts were thus dubbed the Colorado Labor Wars. The WFM also played a key role in the founding of the Industrial Workers of the World in 1905 but left that organization several years later.

William Dudley Haywood, nicknamed "Big Bill", was an American labor organizer and founding member and leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and a member of the executive committee of the Socialist Party of America. During the first two decades of the 20th century, Haywood was involved in several important labor battles, including the Colorado Labor Wars, the Lawrence Textile Strike, and other textile strikes in Massachusetts and New Jersey.

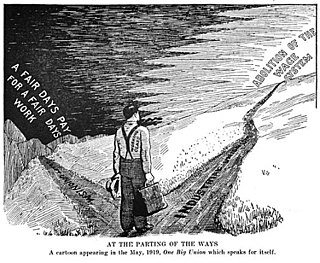

The One Big Union is an idea originating in the late 19th and early 20th centuries amongst trade unionists to unite the interests of workers and offer solutions to all labour problems.

Franklin Henry Little, commonly known as Frank Little, was an American labor leader who was murdered in Butte, Montana. No one was apprehended or prosecuted for Little's murder. He joined the Industrial Workers of the World in 1905, organizing miners, lumberjacks, and oil field workers. He was a member of the union's Executive Board when he was murdered and lynched.

Charles H. Moyer was an American labor leader and president of the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) from 1902 to 1926. He led the union through the Colorado Labor Wars, was accused of murdering an ex-governor of the state of Idaho, and was shot in the back during a bitter copper mine strike. He also was a leading force in founding the Industrial Workers of the World, although he later denounced the organization.

The Cripple Creek miners' strike of 1894 was a five-month strike by the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) in Cripple Creek, Colorado, United States. It resulted in a victory for the union and was followed in 1903 by the Colorado Labor Wars. It is notable for being the only time in United States history when a state militia was called out in support of striking workers.

The 1983 Arizona copper mine strike began as a labour dispute between the Phelps Dodge Corporation and a group of union copper miners and mill workers, led by the United Steelworkers. The subsequent strike lasted nearly three years and resulted in the replacement of most of the striking workers and decertification of the unions. It is regarded as an important event in the history of the United States labor movement.

Labor federation competition in the United States is a history of the labor movement, considering U.S. labor organizations and federations that have been regional, national, or international in scope, and that have united organizations of disparate groups of workers. Union philosophy and ideology changed from one period to another, conflicting at times. Government actions have controlled, or legislated against particular industrial actions or labor entities, resulting in the diminishing of one labor federation entity or the advance of another.

The Colorado Labor Wars were a series of labor strikes in 1903 and 1904 in the U.S. state of Colorado, by gold and silver miners and mill workers represented by the Western Federation of Miners (WFM). Opposing the WFM were associations of mine owners and businessmen at each location, supported by the Colorado state government. The strikes were notable and controversial for the accompanying violence, and the imposition of martial law by the Colorado National Guard in order to put down the strikes.

Labor spying in the United States had involved people recruited or employed for the purpose of gathering intelligence, committing sabotage, sowing dissent, or engaging in other similar activities, in the context of an employer/labor organization relationship. Spying by companies on union activities has been illegal in the United States since the National Labor Relations Act of 1935. However, non-union monitoring of employee activities while at work is perfectly legal and, according to the American Management Association, nearly 80% of major US companies actively monitor their employees.

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) is a union of wage workers which was formed in Chicago in 1905 by militant unionists and their supporters due to anger over the conservatism, philosophy, and craft-based structure of the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Throughout the early part of the 20th century, the philosophy and tactics of the IWW were frequently in direct conflict with those of the AFL concerning the best ways to organize workers, and how to best improve the society in which they toiled. The AFL had one guiding principle—"pure and simple trade unionism", often summarized with the slogan "a fair day's pay for a fair day's work." The IWW embraced two guiding principles, fighting like the AFL for better wages, hours, and conditions, but also promoting an eventual, permanent solution to the problems of strikes, injunctions, bull pens, and union scabbing.

The Copper Country strike of 1913–1914 was a major strike affecting all copper mines in the Copper Country of Michigan. The strike, organized by the Western Federation of Miners, was the first unionized strike within the Copper Country. It was called to achieve goals of shorter work days, higher wages, union recognition, and to maintain family mining groups. The strike lasted just over nine months, including the Italian Hall disaster on Christmas Eve, and ended with the union being effectively driven out of the Keweenaw Peninsula. While unsuccessful, the strike is considered a turning point in the history of the Copper Country.

The Leadville miners' strike was a labor action by the Cloud City Miners' Union, which was the Leadville, Colorado local of the Western Federation of Miners (WFM), against those silver mines paying less than $3.00 per day. The strike lasted from 19 June 1896 to 9 March 1897, and resulted in a major defeat for the union, largely due to the unified opposition of the mine owners. The failure of the strike caused the WFM to leave the American Federation of Labor (AFL), and is regarded as a cause for the WFM turn toward revolutionary socialism.

The 1892 Coeur d'Alene labor strike erupted in violence when labor union miners discovered they had been infiltrated by a Pinkerton agent who had routinely provided union information to the mine owners. The response to the labor violence, disastrous for the local miners' union, became the primary motivation for the formation of the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) the following year. The incident marked the first violent confrontation between the workers of the mines and their owners. Labor unrest continued after the 1892 strike, and surfaced again in the labor confrontation of 1899.

The Butte, Montana labor riots of 1914 were a series of violent clashes between copper miners at Butte, Montana. The opposing factions were the miners dissatisfied with the Western Federation of Miners local at Butte, on the one hand, and those loyal to the union local on the other. The dissident miners formed a new union, and demanded that all miners must join the new union, or be subject to beatings or forced expulsion from the area. Sources disagree whether the dissidents were a majority of the miners, or a militant minority. The leadership of the new union contained many who were members of the Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.), or agreed with the I.W.W.'s methods and objectives. The result of the dispute between rival unions was that the copper mines of Butte, which had long been a union stronghold for the WFM, became open shop employers, and recognized no union from 1914 until 1934.

The Goldfield, Nevada labor troubles of 1906–1907 were a series of strikes and a lockout which pitted gold miners and other laborers, represented by the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), against mine owners and businessmen.

Smeltertown was a residential community in El Paso County, Texas, housing the workers of the ASARCO smelter and their families, between El Paso and the Texas borders with Mexico and New Mexico.

The 1913 Studebaker strike was a labor strike involving workers for the American car manufacturer Studebaker in Detroit. The six-day June 1913 strike, organized by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), is considered the first major labor strike in the automotive industry.

The 1916–1917 northern Minnesota lumber strike was a labor strike involving several thousand sawmill workers and lumberjacks in the northern part of the U.S. state of Minnesota, primarily along the Mesabi Range. The lumber workers were organized by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and primarily worked for the Virginia and Rainy Lake Lumber Company, whose sawmill plant was located in Virginia, Minnesota. Additional lumberjacks and mill workers from the International Lumber Company were also involved. The strike first began with the Virginia and Rainy Lake mill workers on December 28, 1916, and among the lumberjacks on January 1, 1917. The strike lasted for a little over a month before it was officially called off by the union on February 1, 1917. Though the strike faltered by late January and had resulted in many arrests and the suppression of the IWW's local union in the region, the union claimed a partial victory, as the lumber companies instituted some improvements for the lumberjacks' working conditions.