Lake Eyre, officially known as Kati Thanda–Lake Eyre, is an endorheic lake in the east-central part of the Far North region of South Australia, some 700 km (435 mi) north of Adelaide. The shallow lake is the depocentre of the vast endorheic Lake Eyre basin, and contains the lowest natural point in Australia, at approximately 15 m (49 ft) below sea level. On the rare occasions that it fills completely, it is the largest lake in Australia, covering an area of up to 9,500 km2 (3,668 sq mi). When the lake is full, it has the same salinity as seawater, but becomes hypersaline as the lake dries up and the water evaporates.

A rain shadow is an area of significantly reduced rainfall behind a mountainous region, on the side facing away from prevailing winds, known as its leeward side.

The Diamantina River is a major river in Central West Queensland and the far north of South Australia.

The Lake Eyre basin is a drainage basin that covers just under one-sixth of all Australia. It is the largest endorheic basin in Australia and amongst the largest in the world, covering about 1,200,000 square kilometres (463,323 sq mi), including much of inland Queensland, large portions of South Australia and the Northern Territory, and a part of western New South Wales. The basin is also one of the largest, least-developed arid zone basins with a high degree of variability anywhere. It supports only about 60,000 people and has no major irrigation, diversions or flood-plain developments. Low density grazing that sustains a large amount of wildlife is the major land use, occupying 82% of the total land within the basin. The Lake Eyre basin of precipitation to a great extent geographically overlaps the Great Artesian Basin underneath.

The Cooper Creek is a river in the Australian states of Queensland and South Australia. It was the site of the death of the explorers Burke and Wills in 1861. It is sometimes known as the Barcoo River from one of its tributaries and is one of three major Queensland river systems that flow into the Lake Eyre basin. The flow of the creek depends on monsoonal rains falling months earlier and many hundreds of kilometres away in eastern Queensland. It is 1,300 kilometres (810 mi) in length.

The Warrego River is an intermittent river that is part of the Darling catchment within the Murray–Darling basin, which is located in South West Queensland and in the Orana region of New South Wales, Australia. The Warrego River is the northernmost tributary of the Darling River.

The unofficial geographic term Northern Australia includes those parts of Queensland and Western Australia north of latitude 26° and all of the Northern Territory. Those local government areas of Western Australia and Queensland that lie partially in the north are included.

The Georgina River is the north-westernmost of the three major rivers of the Channel Country in Central West Queensland, that also flows through a portion of the Northern Territory, in central Australia. Part of the Lake Eyre basin, the Georgina flows in extremely wet years into Lake Eyre.

Drought in Australia is defined by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology as rainfall over period greater than three-months being in the lowest decile of what has been recorded for that region in the past. This definition takes into account that drought is a relative term and rainfall deficiencies need to be compared to typical rainfall patterns including seasonal variations. Specifically, drought in Australia is defined in relation to a rainfall deficiency of pastoral leases and is determined by decile analysis applied to a certain area. Note that this definition uses rainfall only because long-term records are widely available across most of Australia. However, it does not take into account other variables that might be important for establishing surface water balance, such as evaporation and condensation.

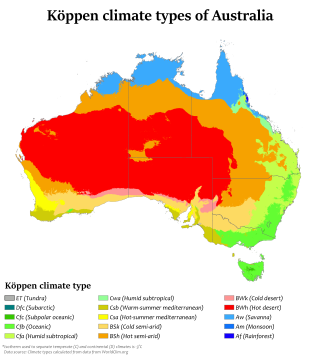

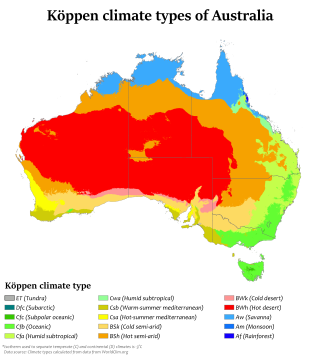

Australia's climate is governed mostly by its size and by the hot, sinking air of the subtropical high pressure belt. This moves north-west and north-east with the seasons. The climate is variable, with frequent droughts lasting several seasons, thought to be caused in part by the El Niño-Southern Oscillation. Australia has a wide variety of climates due to its large geographical size. The largest part of Australia is desert or semi-arid. Only the south-east and south-west corners have a temperate climate and moderately fertile soil. The northern part of the country has a tropical climate, varying between grasslands and desert. Australia holds many heat-related records: the continent has the hottest extended region year-round, the areas with the hottest summer climate, and the highest sunshine duration.

In Australia, the Federation Drought is the name given to a prolonged period of drought that occurred around the time of Federation in 1901.

Between 1979 and 1983 almost all of eastern Australia was affected by a major drought.

The 1911–16 Australian drought consisted of a series of droughts that affected various regions of Australia between the years of 1911 and 1916. Most of the dry spells during this period can be related to three El Niño events in 1911, 1913 and 1914, though rainfall deficiencies actually began in northern Australia before the first of these El Niños set in and did not ease in coastal districts of New South Wales until well after the last El Niño had firmly dissipated and trends toward very heavy rainfall developed in other areas of the continent.

The 2000s drought in Australia, also known as the millennium drought, is said by some to be the worst drought recorded since European settlement.

The 1973–74 Australian region cyclone season was the third most active tropical cyclone season in the Australian Region.

The geography of Queensland in the north-east of Australia, is varied. It includes tropical islands, sandy beaches, flat river plains that flood after monsoon rains, tracts of rough, elevated terrain, dry deserts, rich agricultural belts and densely populated urban areas.

Australian rivers have been subject to devastating floods in New South Wales, recorded since colonisation. Flooding in New South Wales has predominately been caused by excessive flows into rivers located in New South Wales and, to a lesser extent, excessive flows into rivers located in Queensland and Victoria. Floods can devastate local communities and impact the entire local economy.

A black nor'easter is a persistent and potentially violent north-easterly storm that occurs on the east coast of Australia, particularly from southeastern Queensland to southern New South Wales, usually between late spring and early autumn, about two days a year.

Effects of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation in Australia are present across most of Australia, particularly the north and the east, and are one of the main climate drivers of the country. Associated with seasonal abnormality in many areas in the world, Australia is one of the continents most affected and experiences extensive droughts alongside considerable wet periods that cause major floods. There exist three phases — El Niño, La Niña, and Neutral, which help to account for the different states of ENSO. Since 1900, there have been 28 El Niño and 19 La Niña events in Australia including the current 2023 El Niño event, which was declared on 17th of September in 2023. The events usually last for 9 to 12 months, but some can persist for two years, though the ENSO cycle generally operates over a time period from one to eight years.

2022 was an extremely wet year for Australia, coming out of a back-to-back La Niña in the summer of 2021-22, a Negative Indian Ocean Dipole developing over the winter and a third back-to-back La Niña in the spring of 2022.