The last Soviet Union (USSR)-era flag was adopted by the Russian SFSR in 1954 and used until 1991. The flag of the Russian SFSR was a defacement of the flag of the Soviet Union. The constitution stipulated:

The state flag of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (SFSR) presents itself as a red, rectangular sheet with a light-blue stripe at the pole extending all the width [read height] which constitutes one eighth length of the flag.

An Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was a type of administrative unit in the Soviet Union (USSR) created for certain nations. The ASSRs had a status lower than the constituent union republics of the USSR, but higher than the autonomous oblasts and the autonomous okrugs.

During the existence of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, different governments existed within the Crimean Peninsula. From 1921 to 1936, the government in the Crimean Peninsula was known as the Crimean Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic and was an Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic located within the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic; from 1936 to 1945, it was called the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic.

The coat of arms of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic was adopted on 14 March 1919 by the government of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic and subsequently modified on 7 November 1928, 30 January 1937 and 21 November 1949. The coat of arms from 1949 is based on the coat of arms of the Soviet Union and features the hammer and sickle, the red star, a sunrise and stalks of wheat on its outer rims. The rising sun stands for the future of the Soviet Ukrainian nation, the red star as well as the hammer and sickle for communism and the "world-wide socialist community of states".

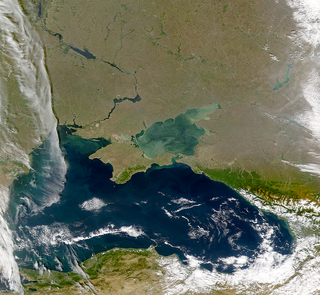

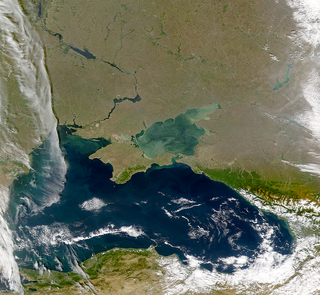

The recorded history of the Crimean Peninsula, historically known as Tauris, Taurica, and the Tauric Chersonese, begins around the 5th century BC when several Greek colonies were established along its coast, the most important of which was Chersonesos near modern day Sevastopol, with Scythians and Tauri in the hinterland to the north. The southern coast gradually consolidated into the Bosporan Kingdom which was annexed by Pontus and then became a client kingdom of Rome. The south coast remained Greek in culture for almost two thousand years including under Roman successor states, the Byzantine Empire, the Empire of Trebizond, and the independent Principality of Theodoro. In the 13th century, some Crimean port cities were controlled by the Venetians and by the Genovese, but the interior was much less stable, enduring a long series of conquests and invasions. In the medieval period, it was partially conquered by Kievan Rus' whose prince Vladimir the Great was baptised at Sevastopol, which marked the beginning of the Christianization of Kievan Rus'. During the Mongol invasion of Europe, the north and centre of Crimea fell to the Mongol Golden Horde, and in the 1440s the Crimean Khanate formed out of the collapse of the horde but quite rapidly itself became subject to the Ottoman Empire, which also conquered the coastal areas which had kept independent of the Khanate. A major source of prosperity in these times was frequent raids into Russia for slaves.

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic,Russian SFSR or RSFSR, previously known as the Russian Soviet Republic and the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic as well as being unofficially known as Soviet Russia, the Russian Federation or simply Russia, was an independent federal socialist state from 1917 to 1922, and afterwards the largest and most populous of the Soviet socialist republics of the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1922 to 1991, until becoming a sovereign part of the Soviet Union with priority of Russian laws over Union-level legislation in 1990 and 1991, the last two years of the existence of the USSR. The Russian Republic was composed of sixteen smaller constituent units of autonomous republics, five autonomous oblasts, ten autonomous okrugs, six krais and forty oblasts. Russians formed the largest ethnic group. The capital of the Russian SFSR was Moscow and the other major urban centers included Leningrad, Stalingrad, Novosibirsk, Sverdlovsk, Gorky and Kuybyshev. It was first Marxist-Leninist state in the world.

The Russia–Ukraine border is the international state border between the Russian Federation and Ukraine. Over land the border outlines five oblasts (regions) of Ukraine and five oblasts of the Russian Federation. The modern border issue has been ongoing ever since the fall of the Russian Empire in 1917.

The Declaration and Treaty on the Formation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics officially created the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union. It de jure legalised a political union of several Soviet republics that had existed since 1919 and created a new federal government whose key functions were centralised in Moscow. Its legislative branch consisted of the Congress of Soviets of the Soviet Union and the Central Executive Committee of the Soviet Union (TsIK), while the Council of People's Commissars composed the executive.

A referendum on sovereignty was held in the Crimean Oblast of the Ukrainian SSR on 20 January 1991, two months before the 1991 All-Union referendum. Voters were asked whether they wanted to re-establish the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, which had been abolished in 1945. The proposal was approved by 94% of voters.

Soniachna Dolyna or Solnechnaya Dolina(Ukrainian: Сонячна Долина; Russian: Солнечная Долина; literally, Sunny Valley) is a village in the Sudak Municipality of the Crimea, a territory recognized by a majority of countries as part of Ukraine and annexed by Russia as the Republic of Crimea.

Myndalne or Mindalnoye(Ukrainian: Миндальне; Russian: Миндальное) is a village in the Sudak Municipality of the Crimea, a territory recognized by a majority of countries as part of Ukraine and annexed by Russia as the Republic of Crimea.

A variety of social, economical, cultural, ethnic, and linguistic factors contributed to the sparking of unrest in eastern and southern Ukraine in 2014, and the subsequent eruption of the Russo-Ukrainian War, in the aftermath of the early 2014 Revolution of Dignity. Following Ukrainian independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, resurfacing historical and cultural divisions and a weak state structure hampered the development of a unified Ukrainian national identity. In eastern and southern Ukraine, Russification and ethnic Russian settlement during centuries of Russian rule caused the Russian language to attain primacy, even amongst ethnic Ukrainians. In Crimea, ethnic Russians have comprised the majority of the population since the deportation of the indigenous Crimean Tatars by Soviet general secretary Joseph Stalin following the Second World War. This contrasts with western and central Ukraine, which were historically ruled by a variety of powers, such as the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Austrian Empire. In these areas, the Ukrainian ethnic, national, and linguistic identity remained intact.

Vesele or Vesyoloye(Ukrainian: Веселе; Russian: Весёлое) is a village in the Sudak Municipality of the Crimea, a territory recognized by a majority of countries as part of Ukraine and annexed by Russia as the Republic of Crimea.

Bahativka or Bogatovka is a village in the Sudak Municipality of the Crimea, a territory recognized by a majority of countries as part of Ukraine and annexed by Russia as the Republic of Crimea.

Dachne is a village in the Sudak Municipality of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, a territory recognized by a majority of countries as part of Ukraine and annexed by Russia as the Republic of Crimea.

Hromivka or Gromovka is a village in the Sudak Municipality of the Crimea, a territory recognized by a majority of countries as part of Ukraine and annexed by Russia as the Republic of Crimea.

Kholodivka or Kholodovka is a village in the Sudak Municipality of the Crimea, a territory recognized by a majority of countries as part of Ukraine and annexed by Russia as the Republic of Crimea.

Lisne or Lesnoye is a village in the Sudak Municipality of the Crimea, a territory recognized by a majority of countries as part of Ukraine and annexed by Russia as the Republic of Crimea.

Mizhrichchia or Mezhdurechye is a village in the Sudak Municipality of the Crimea, a territory recognized by a majority of countries as part of Ukraine and annexed by Russia as the Republic of Crimea.

Perevalivka is a village in the Sudak Municipality of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, a territory recognized by a majority of countries as part of Ukraine and annexed by Russia as the Republic of Crimea.