The Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (1972–2002) was an arms control treaty between the United States and the Soviet Union on the limitation of the anti-ballistic missile (ABM) systems used in defending areas against ballistic missile-delivered nuclear weapons. It was intended to reduce pressures to build more nuclear weapons to maintain deterrence. Under the terms of the treaty, each party was limited to two ABM complexes, each of which was to be limited to 100 anti-ballistic missiles.

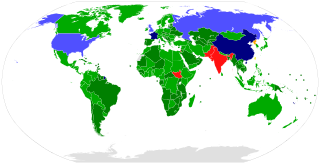

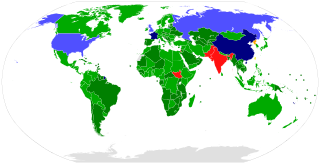

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, commonly known as the Non-Proliferation Treaty or NPT, is an international treaty whose objective is to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology, to promote cooperation in the peaceful uses of nuclear energy, and to further the goal of achieving nuclear disarmament and general and complete disarmament. Between 1965 and 1968, the treaty was negotiated by the Eighteen Nation Committee on Disarmament, a United Nations-sponsored organization based in Geneva, Switzerland.

START I was a bilateral treaty between the United States and the Soviet Union on the reduction and the limitation of strategic offensive arms. The treaty was signed on 31 July 1991 and entered into force on 5 December 1994. The treaty barred its signatories from deploying more than 6,000 nuclear warheads and a total of 1,600 intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and bombers.

The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty was an arms control treaty between the United States and the Soviet Union. US President Ronald Reagan and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev signed the treaty on 8 December 1987. The US Senate approved the treaty on 27 May 1988, and Reagan and Gorbachev ratified it on 1 June 1988.

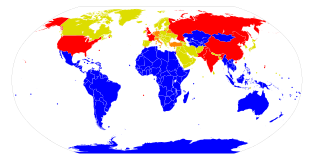

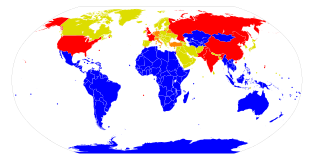

The Russian Federation is known to possess or have possessed three types of weapons of mass destruction: nuclear weapons, biological weapons, and chemical weapons. It is one of the five nuclear-weapon states recognized under the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons.

The Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany , or the Two Plus Four Agreement , is an international agreement that allowed the reunification of Germany in the early 1990s. It was negotiated in 1990 between the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic, and the Four Powers which had occupied Germany at the end of World War II in Europe: France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States. In the treaty, the Four Powers renounced all rights they held in Germany, allowing a reunited Germany to become fully sovereign the following year. At the same time, the two German states agreed to confirm their acceptance of the existing border with Poland, and accepted that the borders of Germany after unification would correspond only to the territories then administered by West and East Germany, with the exclusion and renunciation of any other territorial claims.

As the collapse of the Soviet Union appeared imminent, the United States and their NATO allies grew concerned of the risk of nuclear weapons held in the Soviet republics falling into enemy hands. The Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) program was initiated by the Nunn–Lugar Act, which was authored and cosponsored by Sens. Sam Nunn (D-GA) and Richard Lugar (R-IN). According to the CTR website, the purpose of the CTR Program was originally "to secure and dismantle weapons of mass destruction and their associated infrastructure in former Soviet Union states." As the peace dividend grew old, an alternative 2009 explanation of the program was "to secure and dismantle weapons of mass destruction in states of the former Soviet Union and beyond". The CTR program funds have been disbursed since 1997 by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA).

The original Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) was negotiated and concluded during the last years of the Cold War and established comprehensive limits on key categories of conventional military equipment in Europe and mandated the destruction of excess weaponry. The treaty proposed equal limits for the two "groups of states-parties", the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the Warsaw Pact. In 2007, Russia "suspended" its participation in the treaty, and on 10 March 2015, citing NATO's de facto breach of the Treaty, Russia formally announced it was "completely" halting its participation in it as of the next day.

Unilateral disarmament is a policy option, to renounce weapons without seeking equivalent concessions from one's actual or potential rivals. It was most commonly used in the twentieth century in the context of unilateral nuclear disarmament, a recurrent objective of peace movements in countries such as the United Kingdom.

The Collective Security Treaty Organization is an intergovernmental military alliance in Eurasia. The CSTO consists of select post-Soviet states. The treaty had its origins in the Soviet Armed Forces, which was replaced by the United Armed Forces of the Commonwealth of Independent States, and then by the successor armed forces of the respective independent states.

The Central Asian Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone (CANWFZ) treaty is a legally binding commitment by Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan not to manufacture, acquire, test, or possess nuclear weapons. The treaty was signed on 8 September 2006 at Semipalatinsk Test Site, Kazakhstan, and is also known as Treaty of Semipalatinsk, Treaty of Semei, or Treaty of Semey.

The relationship between Ukraine and the United Kingdom has been strong. Ukraine and the UK have partners in politics, military and economically. Both share similar values regarding freedom of expression, democracy and human rights. Due to many factors Ukraine has been called by some as "Britain's closest European ally".

Russia–Ukraine relations are the bilateral ties between the Russian Federation and Ukraine. Following the Ukrainian Revolution of Dignity in 2014, Ukraine's Crimean Peninsula was occupied by unmarked Russian forces, and later annexed by Russia, while pro-Russia separatists simultaneously engaged the Ukrainian military in an armed conflict for control over eastern Ukraine; these events marked the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian War. In a major escalation of the conflict on 24 February 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of the Ukrainian mainland across a broad front, causing Ukraine to sever all formal diplomatic ties with Russia.

Prior to 1991, Ukraine was part of the Soviet Union and had Soviet nuclear weapons in its territory. On December 1, 1991, Ukraine, the second most powerful republic in the Soviet Union (USSR), voted overwhelmingly for independence, which ended any realistic chance of the Soviet Union staying together even on a limited scale. More than 90% of the electorate expressed their support for Ukraine's declaration of independence, and they elected the chairman of the parliament, Leonid Kravchuk, as the first president of the country. At the meetings in Brest, Belarus on December 8, and in Alma Ata on December 21, the leaders of Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine formally dissolved the Soviet Union and formed the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

A security assurance, in the context of nuclear warfare, is an expression of a political position by a nuclear-armed nation intended to placate other non-nuclear-armed nations. There are two types of security assurance: positive and negative. A positive assurance states that the nation giving it will aid any or a particular non-nuclear-armed nation in retaliation if it is a victim of nuclear attack. A negative assurance is not the opposite but instead means that a nuclear-armed nation has promised not to use nuclear weapons except in retaliation for a nuclear attack against itself.

The Lisbon Protocol to the 1991 Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty was a document signed by representatives of Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan that recognized the four states as successors of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and all of them assume obligations of the Soviet Union under the START I treaty. The protocol was signed in Lisbon, Portugal, on 23 May 1992.

International reactions to the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation have largely been condemnatory of Russia's actions, supportive of Ukraine's sovereignty and territorial integrity, and supportive of finding a quick end to the crisis. The United States and the European Union threatened and later enacted sanctions against Russia for its role in the crisis, and urged Russia to withdraw. Russia has accused the United States and the EU of funding and directing the revolution and retaliated to the sanctions by imposing its own.

Soviet Nuclear Threat Reduction Act of 1991, 22 U.S.C. § 2551, was chartered to amend the Arms Export Control Act enacting the transfer of Soviet military armaments and ordnances to NATO marking the conclusion of the Cold War. The Act sanctions the Soviet nuclear arsenal displacement shall be in conjunction with the implementation of the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe. It funds the Nunn–Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction program.

The collapse of the Soviet Union made Kazakhstan, the fourth-largest nuclear power in the world, leading to its rapid denuclearization. Formally known as the Kazakh Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, the former republic had a considerably large nuclear infrastructure due to its reliance on civilian nuclear programs as a means to develop its economy. The nuclear infrastructure and economy of Kazakhstan heavily depended on the cooperation between their country and Russia since its inception as an independent country.