The Estonian Centre Party is a left-centrist political party in Estonia. It was founded in 1991 as a direct successor of the Popular Front of Estonia, and it is currently led by Mihhail Kõlvart.

The Estonian Reform Party is a liberal political party in Estonia. The party has been led by Kaja Kallas since 2018. It is colloquially known as the "Squirrel Party", referencing its logo.

Edgar Savisaar was an Estonian politician, one of the founding members of Popular Front of Estonia and the Centre Party. He served as the acting Prime Minister of Estonia, Minister of the Interior, Minister of Economic Affairs and Communications, and twice mayor of Tallinn.

The Social Democratic Party is a centre-left political party in Estonia. It is currently led by Lauri Läänemets. The party was formerly known as the Moderate People's Party. The SDE has been a member of the Party of European Socialists since 16 May 2003 and was a member of the Socialist International from November 1990 to 2017. It is orientated towards the principles of social-democracy, and it supports Estonia's membership in the European Union. From April 2023, the party has been a junior coalition partner in the third Kallas government.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Estonia since 1 January 2024. The government elected in the March 2023 election, led by Prime Minister Kaja Kallas and consisting of the Reform Party, the Social Democrats and Estonia 200, vowed to legalize same-sex marriage. Legislation to open marriage to same-sex couples was introduced to the Riigikogu in May 2023, and was approved in a final reading by 55 votes to 34 on 20 June. It was signed into law by President Alar Karis on 27 June, and took effect on 1 January 2024. Estonia was the first Baltic state, the twentieth country in Europe, and the 35th in the world to legalise same-sex marriage.

Jüri Ratas is an Estonian politician who was the 18th prime minister of Estonia from 2016 to 2021. He was the Leader of the Centre Party from 2016 to 2023, and the mayor of Tallinn from 2005 to 2007. Ratas was a member of the Centre Party until switching to Isamaa in 2024.

Parliamentary elections were held in Estonia on 4 March 2007. The newly elected 101 members of the 11th Riigikogu assembled at Toompea Castle in Tallinn within ten days of the election. It was the world's first nationwide vote where part of the voting was carried out in the form of remote electronic voting via the internet.

Isamaa is a Christian-democratic and national-conservative political party in Estonia.

Taavi Rõivas is an Estonian politician, former Prime Minister of Estonia from 2014 to 2016 and former leader of the Reform Party. Before his term as the Prime Minister, Rõivas was the Minister of Social Affairs from 2012 to 2014. On 9 November 2016 his second cabinet dissolved after coalition partners, Union of Pro Patria and Res Publica and Social Democratic Party, sided with the opposition in a no confidence motion. At the end of 2020, Rõivas announced quitting politics, and resigned from his parliament seat.

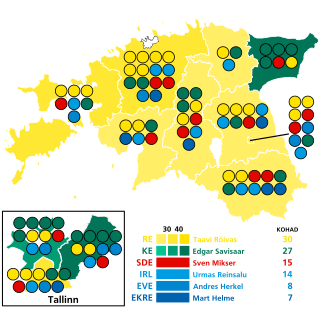

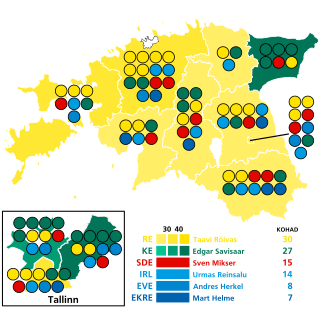

Parliamentary elections were held in Estonia on 1 March 2015. Advance voting was held between 19 and 25 February with a turnout of 33 percent. The Reform Party remained the largest in the Riigikogu, winning 30 of the 101 seats. Its leader, Taavi Rõivas, remained Prime Minister. The newly elected 101 members of the 13th Riigikogu assembled at Toompea Castle in Tallinn within ten days of the election. Two political newcomers, the Free Party and the Conservative People's Party (EKRE) crossed the threshold to enter the Riigikogu.

Kaja Kallas is an Estonian politician and the current prime minister of Estonia since 2021, the first woman to serve in the role. The leader of the Reform Party since 2018, she was a member of parliament (Riigikogu) in 2011–2014, and 2019–2021. Kallas was a member of the European Parliament in 2014–2018, representing the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe. Before her election to Riigikogu, she was a lawyer specialising in European competition law.

Estonia 200 is a liberal political party in Estonia. Since April 2023, the party has been a junior partner in the third Kallas government. In the European Parliament, the party is a member of the Renew Europe group.

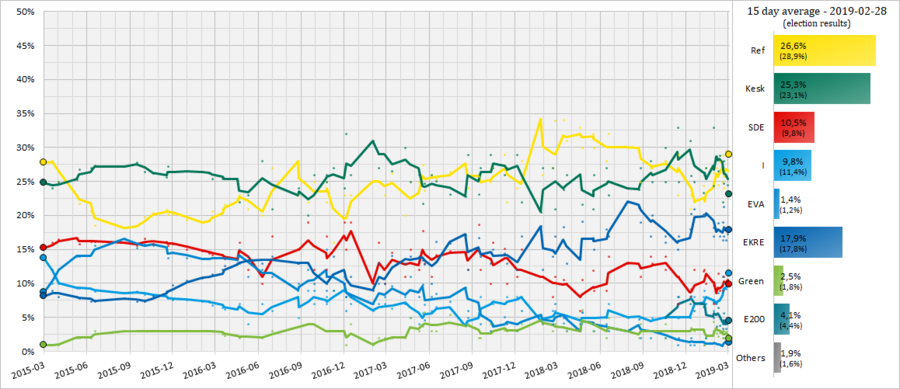

Events of 2019 in Estonia.

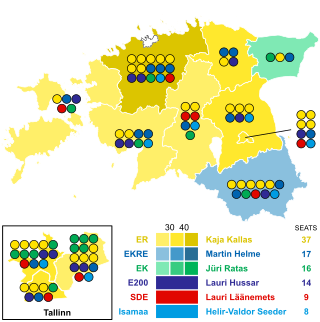

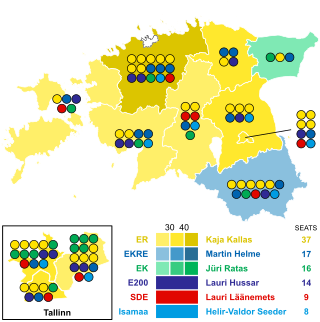

Parliamentary elections were held in Estonia on 5 March 2023 to elect all 101 members of the Riigikogu. The officially published election data indicate the victory of the Reform Party, which won 37 seats in total, while the Conservative People's Party of Estonia (EKRE) placed second with 17 seats. The Centre Party won 16 seats, a loss of 10, while Estonia 200 won 14 seats, gaining representation in the Riigikogu.

Jüri Ratas's second cabinet was the 50th cabinet of Estonia, in office from 29 April 2019 to 14 January 2021. It was a centre-right coalition cabinet of the Centre Party, right-wing populist Conservative People's Party (EKRE) and conservative Isamaa.

An election for the Members of the European Parliament from Estonia will take place on June 9.

An indirect election took place in Estonia on 30 and 31 August 2021 to elect the president of Estonia, who is the country's head of state. The Riigikogu — the Parliament of Estonia — elected Alar Karis to serve in the office and he was sworn in as the 6th president on 11 October 2021. The incumbent, Kersti Kaljulaid, was eligible to seek reelection to a second, and final, term but failed to gain the endorsement of at least 21 MPs, which is required in order for a candidate to register, as she was outspoken against some of the policies of the government, who thus denied her support.

Kaja Kallas's first cabinet was the Cabinet of Estonia between 26 January 2021 and 14 July 2022. It was a grand coalition cabinet of the Reform Party and the Centre Party until 3 June 2022 when Kallas dismissed Centre Party ministers from government after several weeks of disputes between the two parties.

The second cabinet of Kaja Kallas, was the cabinet of Estonia from 18 July 2022 until 17 April 2023 when it was succeeded by the third Kallas cabinet following the 2023 election.

Triple Alliance is a commonly used political term in Estonia to refer to the various coalition governments between the centre-left Social Democratic Party, centre-right Reform Party and conservative Isamaa or their predecessors. This coalition has formed four times in history - from 1999 to 2002, from 2007 to 2009, from 2015 to 2016 and from 2022 to 2023. None of the coalitions governments have lasted a full parliamentary term. All of the Triple Alliance cabinets have been the second ones of the respective Prime Minister.