The European Communities Act 1972, also known as the ECA 1972, was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which made legal provision for the accession of the United Kingdom as a member state to the three European Communities (EC) – the European Economic Community, European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom), and the European Coal and Steel Community ; the EEC and ECSC subsequently became the European Union.

Scottish independence is the idea of Scotland regaining its independence and once again becoming a sovereign state, independent from the United Kingdom. The term Scottish independence refers to the political movement that is campaigning to bring it about.

Referendums in the United Kingdom are occasionally held at a national, regional or local level. Historically, national referendums are rare due to the long-standing principle of parliamentary sovereignty. Legally there is no constitutional requirement to hold a national referendum for any purpose or on any issue. However, the UK Parliament is free to legislate through an Act of Parliament for a referendum to be held on any question at any time.

The 1975 United Kingdom European Communities membership referendum, also known variously as the Referendum on the European Community (Common Market), the Common Market referendum and EEC membership referendum, was a non-binding referendum that took place on 5 June 1975 in the United Kingdom (UK) under the provisions of the Referendum Act 1975 to ask the electorate whether the country should continue to remain a member of, or leave, the European Communities (EC) also known at the time as the Common Market — which it had joined as a member state two-and-a-half years earlier on 1 January 1973 under the Conservative government of Edward Heath. The Labour Party's manifesto for the October 1974 general election had promised that the people would decide through the ballot box whether to remain in the EC.

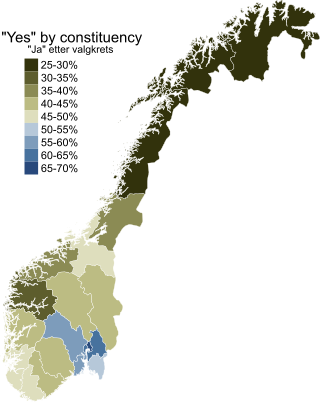

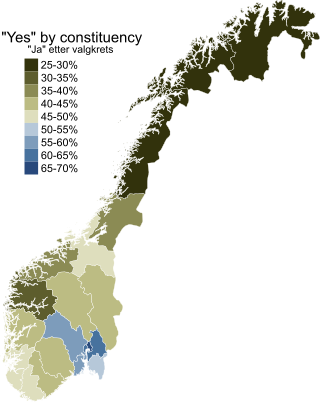

A referendum on joining the European Union was held in Norway on 27 and 28 November 1994. After a long period of heated debate, the "no" side won with 52.2 per cent of the vote, on a turnout of 88.6 per cent. Membership of what was then the European Community had previously been rejected in a 1972 referendum, and by French veto in 1962.

Peter David Shore, Baron Shore of Stepney, was a British Labour Party politician and Cabinet minister, noted in part for his opposition to the United Kingdom's entry into the European Economic Community. He served as a Member of Parliament (MP) for over 30 years, from 1964 to 1997.

Powellism is the name given to the political views of Conservative and Ulster Unionist politician Enoch Powell. They derive from his High Tory and libertarian outlook.

Euroscepticism in the United Kingdom is a continuum of belief ranging from the opposition to certain political policies of the European Union to the complete opposition to the United Kingdom’s membership of the European Union. It has been a significant element in the politics of the United Kingdom (UK). A 2009 Eurobarometer survey of EU citizens showed support for membership of the EU was lowest in the United Kingdom, alongside Latvia and Hungary.

The Oxford Union Society, commonly referred to as the Oxford Union, is a debating society in the city of Oxford, England, whose membership is drawn primarily from the University of Oxford. Founded in 1823, it is one of Britain's oldest university unions and considered one of the world's most prestigious private students' societies. The Oxford Union exists independently from the university and is distinct from the Oxford University Student Union.

A referendum on European Union membership was held in Malta on 8 March 2003. The result was 54% in favour. The subsequent April 2003 general elections were won by the Nationalist Party, which was in favour of EU membership, the opposition Labour Party having opposed joining. Malta joined the EU on 1 May 2004.

A referendum on Scottish independence from the United Kingdom was held in Scotland on 18 September 2014. The referendum question was "Should Scotland be an independent country?", which voters answered with "Yes" or "No". The "No" side won with 2,001,926 (55.3%) voting against independence and 1,617,989 (44.7%) voting in favour. The turnout of 84.6% was the highest recorded for an election or referendum in the United Kingdom since the January 1910 general election, which was held before the introduction of universal suffrage.

The 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, commonly referred to as the EU referendum or the Brexit referendum, was a referendum that took place on 23 June 2016 in the United Kingdom (UK) and Gibraltar under the provisions of the European Union Referendum Act 2015 to ask the electorate whether the country should continue to remain a member of, or leave, the European Union (EU). The result was a vote in favour of leaving the EU, triggering calls to begin the process of the country's withdrawal from the EU commonly termed "Brexit".

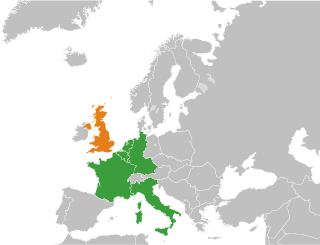

The Treaty of Accession 1972 was the international agreement which provided for the accession of Denmark, Ireland, Norway and the United Kingdom to the European Communities. Norway did not ratify the treaty after it was rejected in a referendum held in September 1972. The treaty was ratified by Denmark, Ireland and the United Kingdom who became EC member states on 1 January 1973 when the treaty entered into force. The treaty remains an integral part of the constitutional basis of the European Union.

Brexit was the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union.

The Referendum Act 1975 also known at the time as the Referendum Bill was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which made legal provision for the holding of a consultative referendum on whether the United Kingdom should remain a member of the European Communities (EC)—generally known at the time in the UK, with reference to their main component, the European Economic Community (EEC) as stipulated in the Act, also known at the time as the "Common Market". The Referendum Bill was introduced to the House of Commons by the Leader of the House of Commons and Lord President of the Council Edward Short on 26 March 1975; on its second reading on 10 April 1975, MPs voted 312–248 in favour of holding the referendum—which came the day after they voted to stay in the European Communities on the new terms set out in the renegotiation.

"Project Fear" is a term that has entered common usage in British politics in the 21st century, mainly in relation to two major referendum debates: the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, and then again during and after the 2016 UK referendum on EU membership (Brexit).

A second referendum on Scotland becoming independent of the United Kingdom (UK) has been proposed by the Scottish Government. An independence referendum was first held on 18 September 2014, with 55% voting "No" to independence. The Scottish Government stated in its white paper for independence that voting Yes was a "once in a generation opportunity to follow a different path, and choose a new and better direction for our nation". Following the "No" vote, the cross party Smith Commission proposed areas that could be devolved to the Scottish Parliament; this led to the passing of the Scotland Act 2016, formalising new devolved policy areas in time for the 2016 Scottish Parliament election campaign.

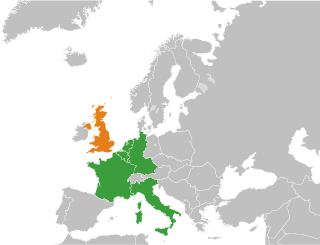

The accession of the United Kingdom to the European Communities (EC) – the collective term for the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), the European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC) – took effect on 1 January 1973. This followed ratification of the Accession treaty which was signed in Brussels on 22 January 1972 by the Conservative prime minister Edward Heath, who had pursued the UK's application to the EEC since the late 1950s. The ECSC and EEC would later be integrated into the European Union under the Maastricht and Lisbon treaties in the early 1990s and mid-2000s.

The result in favour of Brexit of the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum is one of the most significant political events for Britain during the 21st century. The debate provoked major consideration to an array of topics, argued up-to, and beyond, the referendum on 23 June 2016. The referendum was originally conceived by David Cameron as a means to defeat the anti-EU faction within his own party by having it fail. Factors in the vote included sovereignty, immigration, the economy and anti-establishment politics, amongst various other influences. The result of the referendum was that 51.8% of the votes were in favour of leaving the European Union. The formal withdrawal from the EU took place at 23:00 on 31 January 2020, almost three years after Theresa May triggered Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty on 29 March 2017. This page provides an overarching analysis of the different arguments which were presented by both the Leave and Remain campaigns.

The United Kingdom was a member state of the European Union (EU) and of its predecessor the European Communities (EC) – principally the European Economic Community (EEC) – from 1 January 1973 until 31 January 2020. Since the foundation of the EEC, the UK had been an important neighbour and then a leading member state, until Brexit ended 47 years of membership. During the UK's time as a member state two referendums were held on the issue of its membership: the first, held on 5 June 1975, resulting in a vote to stay in the EC, and the second, held on 23 June 2016, resulting in a vote to leave the EU.