Allodaposuchus is an extinct genus of crocodyliforms that lived in what is now southern Europe during the Campanian and Maastrichtian stages, and possibly the Santonian stage, of the Late Cretaceous. Although generally classified as a non-crocodylian eusuchian crocodylomorph, it is sometimes placed as one of the earliest true crocodylians. Allodaposuchus is one of the most common Late Cretaceous crocodylomorphs from Europe, with fossils known from Romania, Spain, and France.

Mahajangasuchus is an extinct genus of crocodyliform which had blunt, conical teeth. The type species, M. insignis, lived during the Late Cretaceous; its fossils have been found in the Maevarano Formation in northern Madagascar. It was a fairly large predator, measuring up to 4 metres (13 ft) long.

Dyrosauridae is a family of extinct neosuchian crocodyliforms that lived from the Campanian to the Eocene. Dyrosaurid fossils are globally distributed, having been found in Africa, Asia, Europe, North America and South America. Over a dozen species are currently known, varying greatly in overall size and cranial shape. A majority were aquatic, some terrestrial and others fully marine, with species inhabiting both freshwater and marine environments. Ocean-dwelling dyrosaurids were among the few marine reptiles to survive the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event.

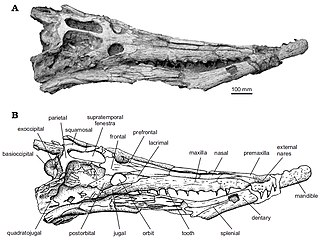

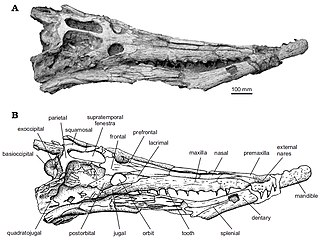

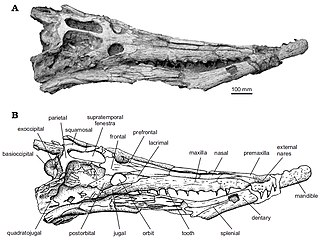

Arambourgisuchus is an extinct genus of dyrosaurid crocodylomorph from the late Palaeocene of Morocco, found in the region of Sidi Chenane in 2000, following collaboration by French and Moroccan institutions, and described in 2005 by a team led by palaeontologist Stéphane Jouve. Arambourgisuchus was a large animal with an elongated skull 1 meter in length.

Scanisaurus is a dubious genus of plesiosaur that lived in what is now Sweden and Russia during the Campanian stage of the Late Cretaceous period. The name Scanisaurus means "Skåne lizard", Skåne being the southernmost province of Sweden, where a majority of the fossils referred to the genus have been recovered. The genus contains one species, S. nazarowi, described in 1911 by Nikolay Bogolyubov as a species of Cimoliasaurus based on a single vertebral centrum discovered near Orenburg, Russia.

Hyposaurus is a genus of extinct marine dyrosaurid crocodyliform. Fossils have been found in Paleocene aged rocks of the Iullemmeden Basin in West Africa, Campanian–Maastrichtian Shendi Formation of Sudan and Maastrichtian through Danian strata in New Jersey, Alabama and South Carolina. Isolated teeth comparable to Hyposaurus have also been found in Thanetian strata of Virginia. It was related to Dyrosaurus. The priority of the species H. rogersii has been debated, however there is no sound basis for the recognition of more than one species from North America. The other North American species are therefore considered nomina vana.

Argochampsa is an extinct genus of eusuchian crocodylomorph, usually regarded as a gavialoid crocodilian, related to modern gharials. It lived in the Paleocene of Morocco. Described by Hua and Jouve in 2004, the type species is A. krebsi, with the species named for Bernard Krebs. Argochampsa had a long narrow snout, and appears to have been marine in habits.

Acynodon is an extinct genus of eusuchian crocodylomorph from the Late Cretaceous, with fossils found throughout Southern Europe.

Eothoracosaurus is an extinct monospecific genus of eusuchian crocodylomorphs found in Eastern United States which existed during the Late Cretaceous period. Eothoracosaurus is considered to belong to an informally named clade called the "thoracosaurs", named after the closely related Thoracosaurus. Thoracosaurs in general were traditionally thought to be related to the modern false gharial, largely because the nasal bones contact the premaxillae, but phylogenetic work starting in the 1990s instead supported affinities within gavialoid exclusive of such forms. Even more recent phylogenetic studies suggest that thoracosaurs might instead be non-crocodilian eusuchians.

Hylaeochampsa is an extinct genus of eusuchian crocodylomorphs. It is known only from a partial skull recovered from Barremian-age rocks of the Lower Cretaceous Vectis Formation of the Isle of Wight. This skull, BMNH R 177, is short and wide, with a eusuchian-like palate and inferred enlarged posterior teeth that would have been suitable for crushing. Hylaochampsa was described by Richard Owen in 1874, with H. vectiana as the type species. It may be the same genus as the slightly older Heterosuchus, inferred to have been of similar evolutionary grade, but there is no overlapping material as Heterosuchus is known only from vertebrae. If the two could be shown to be synonyms, Hylaeochampsa would have priority because it is the older name. Hylaeochampsa is the type genus of the family Hylaeochampsidae, which also includes Iharkutosuchus from the Late Cretaceous of Hungary. James Clark and Mark Norell positioned it as the sister group to Crocodylia. Hylaeochampsa is currently the oldest known unambiguous eusuchian.

Thoracosaurus is an extinct genus of long-snouted eusuchian which existed during the Late Cretaceous and Early Paleocene in North America and Europe.

Pholidosaurus is an extinct genus of neosuchian crocodylomorph. It is the type genus of the family Pholidosauridae. Fossils have been found in northwestern Germany. The genus is known to have existed during the Berriasian-Albian stages of the Early Cretaceous. Fossil material found from the Annero and Jydegård Formations in Skåne, Sweden and on the island of Bornholm, Denmark, have been referred to as a mesoeucrocodylian, and possibly represent the genus Pholidosaurus.

Phosphatosaurus is an extinct genus of dyrosaurid crocodylomorph. It existed during the early Eocene, with fossils having been found from North Africa in Tunisia and Mali. Named in 1955, Phosphatosaurus is a monotypic genus; the type species is P. gavialoides. A specimen has been discovered from Niger, but it cannot be classified at the species level.

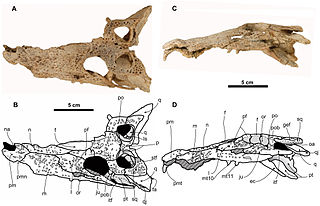

Cerrejonisuchus is an extinct genus of dyrosaurid crocodylomorph. It is known from a complete skull and mandible from the Cerrejón Formation in northeastern Colombia, which is Paleocene in age. Specimens belonging to Cerrejonisuchus and to several other dyrosaurids have been found from the Cerrejón open-pit coal mine in La Guajira. The length of the rostrum is only 54-59% of the total length of the skull, making the snout of Cerrejonisuchus the shortest of all dyrosaurids.

Rhabdognathus is an extinct genus of dyrosaurid crocodylomorph. It is known from rocks dating to the Paleocene epoch from western Africa, and specimens dating back to the Maastrichtian era were identified in 2008. It was named by Swinton in 1930 for a lower jaw fragment from Nigeria. The type species is Rhabdognathus rarus. Stéphane Jouve subsequently assessed R. rarus as indeterminate at the species level, but not at the genus level, and thus dubious. Two skulls which were assigned to the genus Rhabdognathus but which could not be shown to be identical to R. rarus were given new species: R. aslerensis and R. keiniensis, both from Mali. The genus formerly contained the species Rhabdognathus compressus, which was reassigned to Congosaurus compressus after analysis of the lower jaw of a specimen found that it was more similar to that of the species Congosaurus bequaerti. Rhabdognathus is believed to be the closest relative to the extinct Atlantosuchus.

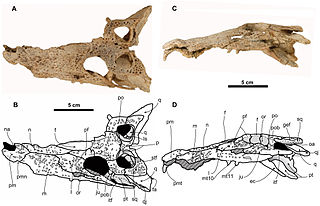

Arenysuchus is an extinct monospecific genus of allodaposuchid eusuchian crocodylomorph from Late Cretaceous deposits of north Spain. It is known from the holotype MPZ ELI-1, a partial skull from Elías site, and from the referred material MPZ2010/948, MPZ2010/949, MPZ2010/950 and MPZ2010/951, four teeth from Blasi 2 site. It was found by the researchers José Manuel Gasca and Ainara Badiola from the Tremp Formation, in Arén of Huesca, Spain. It was first named by Eduardo Puértolas, José I. Canudo and Penélope Cruzado-Caballero in 2011 and the type species is Arenysuchus gascabadiolorum.

Lohuecosuchus is an extinct genus of allodaposuchid eusuchian crocodylomorph that lived during the Late Cretaceous in what is now Spain and southern France.

Agaresuchus is an extinct genus of allodaposuchid eusuchian crocodylomorph from the Late Cretaceous (Campanian-Maastrichtian) of Spain. It includes two species, the type species A. fontisensis, and A. subjuniperus, which was originally named as a species of the related genus Allodaposuchus. However, it has been proposed that both species may instead belong to the genus Allodaposuchus.

The Kristianstad Basin is a Cretaceous-age structural basin and geological formation in northeastern Skåne, the southernmost province of Sweden. The basin extends from Hanöbukten, a bay in the Baltic Sea, in the east to the town of Hässleholm in the west and ends with the two horsts Linderödsåsen and Nävlingeåsen in the south. The basin's northern boundary is more diffuse and there are several outlying portions of Cretaceous-age sediments. During the Cretaceous, the region was a shallow subtropical to temperate inland sea and archipelago.

The Kristianstad Basin is a Cretaceous-age structural basin and geological formation in northeastern Skåne, the southernmost province of Sweden. The sediments in the basin preserves a wide assortment of taxa represented in its fossil record, including the only non-avian dinosaur fossils in Sweden and one of the world's most diverse mosasaur faunas.