The Tlingit or Lingít are Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America and constitute two of the 231 federally recognized Tribes of Alaska. Most Tlingit are Alaska Natives; however, some are First Nations in Canada.

Storytelling is the social and cultural activity of sharing stories, sometimes with improvisation, theatrics or embellishment. Every culture has its own narratives, which are shared as a means of entertainment, education, cultural preservation or instilling moral values. Crucial elements of stories and storytelling include plot, characters and narrative point of view. The term "storytelling" can refer specifically to oral storytelling but also broadly to techniques used in other media to unfold or disclose the narrative of a story.

The Hocągara (Ho-Chungara) or Hocąks (Ho-Chunks) are a Siouan-speaking Native American Nation originally from Wisconsin and northern Illinois. Due to forced emigration in the 19th century, they now constitute two individual tribes; the Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin and the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska. They are most closely related to the Chiwere peoples, and more distantly to the Dhegiha.

Tsimshian mythology is the mythology of the Tsimshian, an Aboriginal people in Canada and a Native American tribe in the United States. The majority of Tsimshian people live in British Columbia, while others live in Alaska.

The Haida are one of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. Their national territories lie along the west coast of Canada and include parts of south east Alaska. Haida mythology is an indigenous religion that can be described as a nature religion, drawing on the natural world, seasonal patterns, events and objects for questions that the Haida pantheon provides explanations for. Haida mythology is also considered animistic for the breadth of the Haida pantheon in imbuing daily events with Sǥā'na qeda's.

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas comprise numerous different cultures. Each has its own mythologies, many of which share certain themes across cultural boundaries. In North American mythologies, common themes include a close relation to nature and animals as well as belief in a Great Spirit that is conceived of in various ways. As anthropologists note, their great creation myths and sacred oral tradition in whole are comparable to the Christian Bible and scriptures of other major religions.

A narrative, story, or tale is any account of a series of related events or experiences, whether non-fictional or fictional. Narratives can be presented through a sequence of written or spoken words, through still or moving images, or through any combination of these. The word derives from the Latin verb narrare, which is derived from the adjective gnarus. The formal and literary process of constructing a narrative—narration—is one of the four traditional rhetorical modes of discourse, along with argumentation, description, and exposition. This is a somewhat distinct usage from narration in the narrower sense of a commentary used to convey a story. Many additional narrative techniques, particularly literary ones, are used to build and enhance any given story.

Nanabozho, also known as Nanabush, is a spirit in Anishinaabe aadizookaan, particularly among the Ojibwe. Nanabozho figures prominently in their storytelling, including the story of the world's creation. Nanabozho is the Ojibwe trickster figure and culture hero.

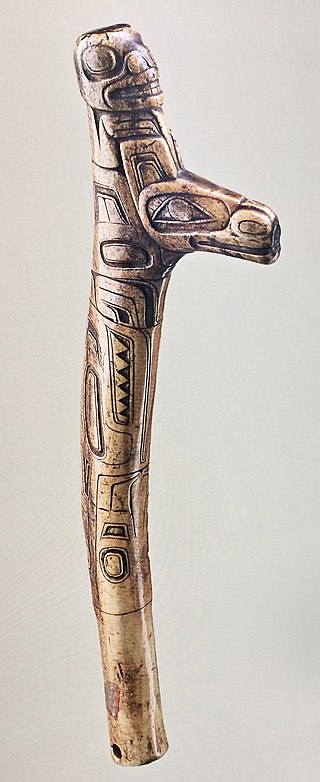

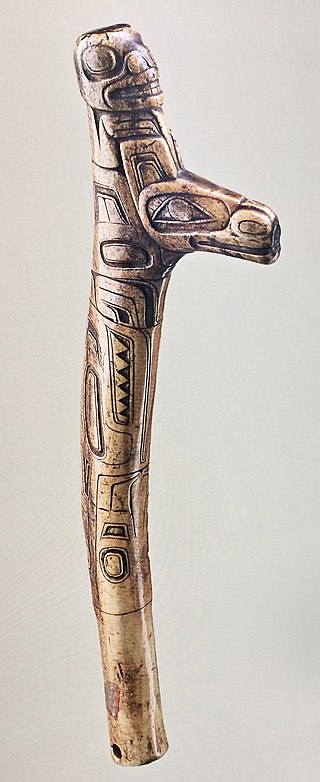

Raven Tales are the traditional human and animal creation stories of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. They are also found among Athabaskan-speaking peoples and others. Raven stories exist in nearly all of the First Nations throughout the region but are most prominent in the tales of the Haida, Tsimshian, Tlingit and Tahltan people.

Coyote is a mythological character common to many cultures of the Indigenous peoples of North America, based on the coyote animal. This character is usually male and is generally anthropomorphic, although he may have some coyote-like physical features such as fur, pointed ears, yellow eyes, a tail and blunt claws. The myths and legends which include Coyote vary widely from culture to culture.

Many references to ravens exist in world lore and literature. Most depictions allude to the appearance and behavior of the wide-ranging common raven. Because of its black plumage, croaking call, and diet of carrion, the raven is often associated with loss and ill omen. Yet, its symbolism is complex. As a talking bird, the raven also represents prophecy and insight. Ravens in stories often act as psychopomps, connecting the material world with the world of spirits.

The history of the Tlingit includes pre- and post-contact events and stories. Tradition-based history involved creation stories, the Raven Cycle and other tangentially-related events during the mythic age when spirits transformed back and forth from animal to human and back, the migration story of arrival at Tlingit lands, and individual clan histories. More recent tales describe events near the time of the first contact with Europeans. European and American historical records come into play at that point; although modern Tlingit have access to those historical records, however, they maintain their own record of ancestors and events important to them against the background of a changing world.

Kutkh is a Raven spirit traditionally revered in various forms by various indigenous peoples of the Russian Far East. Kutkh appears in many legends: as a key figure in creation, as a fertile ancestor of mankind, as a mighty shaman and as a trickster. He is a popular subject of the animist stories of the Chukchi people and plays a central role in the mythology of the Koryaks and Itelmens of Kamchatka. Many of the stories regarding Kutkh are similar to those of the Raven among the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, suggesting a long history of indirect cultural contact between Asian and North American peoples.

Br'er Rabbit is a central figure in an oral tradition passed down by African-Americans of the Southern United States and African descendants in the Caribbean, notably Afro-Bahamians and Turks and Caicos Islanders. He is a trickster who succeeds by his wits rather than by brawn, provoking authority figures and bending social mores as he sees fit. Popular adaptations of the character, originally recorded by Joel Chandler Harris in the 19th century, include Walt Disney Productions' Song of the South in 1946.

Oral storytelling is an ancient and intimate tradition between the storyteller and their audience. The storyteller and the listeners are physically close, often seated together in a circular fashion. The intimacy and connection are deepened by the flexibility of oral storytelling which allows the tale to be molded according to the needs of the audience and the location or environment of the telling. Listeners also experience the urgency of a creative process taking place in their presence and they experience the empowerment of being a part of that creative process. Storytelling creates a personal bond with the teller and the audience.

The Storyteller is a novel by Peruvian author and Literature Nobel Prize winner Mario Vargas Llosa. The story tells of Saúl Zuratas, a university student who leaves civilization and becomes a "storyteller" for the Machiguenga Native Americans. The novel thematizes the Westernization of indigenous peoples through missions and through anthropological studies, and questions the perceived notion that indigenous cultures are set in stone.

Ernestine Saankaláxt Hayes is a Tlingit author and an Emerita professor at the University of Alaska Southeast in Juneau, Alaska. She belongs to the Wolf House of the Kaagwaaataan clan of the Eagle side of the Tlingit Nation. Hayes is a memoirist, essayist, and poet. She served as Alaska State Writer Laureate 2017–2018.

Canadian folklore is the traditional material that Canadians pass down from generation to generation, either as oral literature or "by custom or practice". It includes songs, legends, jokes, rhymes, proverbs, weather lore, superstitions, and practices such as traditional food-making and craft-making. The largest bodies of folklore in Canada belong to the aboriginal and French-Canadian cultures. English-Canadian folklore and the folklore of recent immigrant groups have added to the country's folk.

Indigenous cultures in North America engage in storytelling about morality, origin, and education as a form of cultural maintenance, expression, and activism. Falling under the banner of oral tradition, it can take many different forms that serve to teach, remember, and engage Indigenous history and culture. Since the dawn of human history, oral stories have been used to understand the reasons behind human existence. Today, Indigenous storytelling is part of the broader indigenous process of building and transmitting indigenous knowledge.

Trickster: Native American Tales, A Graphic Collection is an anthology of Native American stories in the format of graphic novels. Published in 2010 and edited by Matt Dembicki, Trickster contains twenty-one short stories, all told by Indigenous storytellers from many different native nations. The premise of each short story is to teach a moral lesson or explain how certain natural events happen. All stories contained within the anthology are tales that have been told orally for centuries within Native American tribes. As the title of the collection suggests, each story contains a character that is known and depicted as a Trickster. This character is the main focus of the story and is typically depicted as an animal figure. Many of the tales such as, Coyote and the Pebbles and Rabbit and the Tug-of-War depict the trickster in a more well-known form of a coyote or rabbit. Lesser known characters are depicted as the trickster throughout the remaining stories such as the raven in Raven the Trickster and the racoon in Espun and Grandfather.