A mining accident is an accident that occurs during the process of mining minerals or metals. Thousands of miners die from mining accidents each year, especially from underground coal mining, although accidents also occur in hard rock mining. Coal mining is considered much more hazardous than hard rock mining due to flat-lying rock strata, generally incompetent rock, the presence of methane gas, and coal dust. Most of the deaths these days occur in developing countries, and rural parts of developed countries where safety measures are not practiced as fully. A mining disaster is an incident where there are five or more fatalities.

Easington Colliery is a village in County Durham, England, known for a history of coal mining. It is situated to the north of Horden, a short distance to the east of Easington. It had a population of 4,959 in 2001, and 5,022 at the 2011 Census.

Allerton Bywater is a semi-rural village and civil parish in the south-east of the City of Leeds metropolitan borough in West Yorkshire, England. The population of the civil parish at the 2011 census was 4,717. The village itself is 2 miles (3.2 km) north of Castleford, with neighbouring villages Kippax and Great Preston all providing local amenities. St Aidan's Nature reserve borders the village attracting many visitors with its beauty and charm. Additionally "The Lines Way" bridle path which runs from Garforth through to Allerton following the old train track provides a pleasant route for walkers, joggers and cyclists alike. The River Aire flows through the village to the south-west.

The Oaks explosion, which happened at a coal mine in West Riding of Yorkshire on 12 December 1866, remains the worst mining disaster in England. A series of explosions caused by firedamp ripped through the underground workings at the Oaks Colliery at Hoyle Mill near Stairfoot in Barnsley killing 361 miners and rescuers. It was the worst mining disaster in the United Kingdom until the 1913 Senghenydd explosion in Wales.

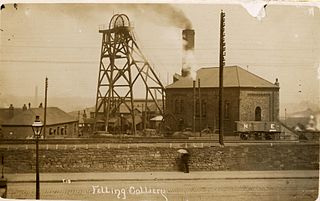

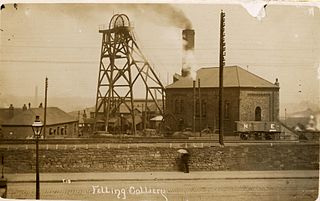

The Felling Colliery in Britain, suffered four disasters in the 19th century, in 1812, 1813, 1821 and 1847. By far the worst of the four was the 1812 disaster which claimed 92 lives on 25 May 1812. The loss of life in the 1812 disaster was one of the motivators for the development of miners' safety lamps such as the Geordie lamp and the Davy lamp.

The Gresford disaster occurred on 22 September 1934 at Gresford Colliery, near Wrexham, when an explosion and underground fire killed 261 men. Gresford is one of Britain's worst coal mining disasters: a controversial inquiry into the disaster did not conclusively identify a cause, though evidence suggested that failures in safety procedures and poor mine management were contributory factors. Further public controversy was caused by the decision to seal the colliery's damaged sections permanently, meaning that the bodies of only 8 of the miners were ever recovered. Two of the three rescue men who died were brought out leaving the third body in situ until recovery operations began the following year.

The Udston mining disaster occurred in Hamilton, Scotland on Saturday, 28 May 1887 when 73 miners died in a firedamp explosion at Udston Colliery. Caused, it is thought, by unauthorised shot firing the explosion is said to be Scotland's second worst coal mining disaster.

The South Yorkshire Coalfield is so named from its position within Yorkshire. It covers most of South Yorkshire, West Yorkshire and a small part of North Yorkshire. The exposed coalfield outcrops in the Pennine foothills and dips under Permian rocks in the east. Its most famous coal seam is the Barnsley Bed. Coal has been mined from shallow seams and outcrops since medieval times and possibly earlier.

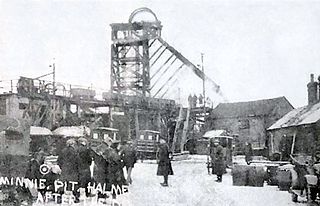

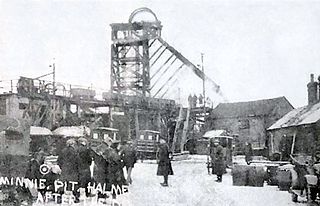

The Minnie Pit disaster was a coal mining accident that took place on 12 January 1918 in Halmer End, Staffordshire, in which 155 men and boys died. The disaster, which was caused by an explosion due to firedamp, is the worst ever recorded in the North Staffordshire Coalfield. An official investigation never established what caused the ignition of flammable gases in the pit.

The West Stanley Pit disasters refers to two explosions in 1882 and 1909 at the West Stanley colliery, a coal mine near Stanley in County Durham, England. The mine opened in 1832 and closed in 1936. Over the years several seams were worked through four shafts: Kettledrum pit, Lamp pit, Mary pit and New pit. The 1882 explosion killed 13 men. In 1909 another explosion took place, killing 168 men. Twenty-nine men survived the latter.

Albion Colliery was a coal mine in South Wales Valleys, located in the village of Cilfynydd, one mile north of Pontypridd.

Gresford Colliery was a coal mine located a mile from the North Wales village of Gresford, near Wrexham.

Maerdy Colliery was a coal mine located in the South Wales village of Maerdy, in the Rhondda Valley, located in the county borough of Rhondda Cynon Taf, and within the historic county boundaries of Glamorgan, Wales. Opened in 1875, it closed in December 1990.

Sir William Galloway was a Scottish mining engineer, professor and industrialist.

Haig Colliery was a coal mine in Whitehaven, Cumbria, in north-west England. The mine was in operation for almost 70 years and produced high volatile strongly caking general purpose coal which was used in the local iron making industry, gas making and domestic fires. In later years, following closure of Workington Steelworks in 1980, it was used in electricity generation at Fiddler's Ferry. Situated on the coast, the underground workings of the mine spread westwards out under the Irish Sea and mining was undertaken at over 4 miles (6.4 km) out underneath the sea bed.

The Cadeby Main Pit Disaster was a coal mining accident on 9 July 1912 which occurred at Cadeby Main Colliery in Cadeby, West Riding of Yorkshire, England, killing 91 men. Early in the morning of 9 July an explosion in the south-west part of the Cadeby Main pit killed 35 men, with three more dying later due to their injuries. Later in the same day, after a rescue party was sent below ground, another explosion occurred, killing 53 men of the rescue party.

Wheldale Colliery was a coal mine located in Castleford, Yorkshire, England which produced coal for 117 years. It was accessed from Wheldon Road.

The Peckfield pit disaster was a mining accident at the Peckfield Colliery in Micklefield, West Yorkshire, England, which occurred on Thursday 30 April 1896, killing 63 men and boys out of 105 who were in the pit, plus 19 out of 23 pit ponies.

The Maypole Colliery disaster was a mining accident on 18 August 1908, when an underground explosion occurred at the Maypole Colliery, in Abram, near Wigan, then in the historic county of Lancashire, in North West England. The final death toll was 75.

The Castleford–Garforth line was a single-track railway line in West Yorkshire, England, connecting Castleford with Garforth east of Leeds. The route was developed to allow coal to be transported from the area, though a passenger service was operated between 1878 and 1951. Initially promoted by Leeds, Castleford and Pontefract Junction Railway, it was taken over by the North Eastern Railway before the line was completed.