The Kingdom of Jerusalem, also known as the Crusader Kingdom, was one of the Crusader states established in the Levant immediately after the First Crusade. It lasted for almost two hundred years, from the accession of Godfrey of Bouillon in 1099 until the fall of Acre in 1291. Its history is divided into two periods with a brief interruption in its existence, beginning with its collapse after the siege of Jerusalem in 1187 and its restoration after the Third Crusade in 1192.

The Sixth Crusade (1228–1229), also known as the Crusade of Frederick II, was a military expedition to recapture Jerusalem and the rest of the Holy Land. It began seven years after the failure of the Fifth Crusade and involved very little actual fighting. The diplomatic maneuvering of the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Sicily, Frederick II, resulted in the Kingdom of Jerusalem regaining some control over Jerusalem for much of the ensuing fifteen years as well as over other areas of the Holy Land.

Buda is the part of Budapest, the capital city of Hungary, that lies on the western bank of the Danube. Historically, “Buda” referred only to the royal walled city on Castle Hill, which was constructed by Béla IV between 1247 and 1249 and subsequently served as the capital of the Kingdom of Hungary from 1361 to 1873. In 1873, Buda was administratively unified with Pest and Óbuda to form modern Budapest.

The Eighth Crusade was the second Crusade launched by Louis IX of France, this one against the Hafsid dynasty in Tunisia in 1270. It is also known as the Crusade of Louis IX Against Tunis or the Second Crusade of Louis. The Crusade did not see any significant fighting as Louis died of dysentery shortly after arriving on the shores of Tunisia. The Treaty of Tunis was negotiated between the Crusaders and the Hafsids. No changes in territory occurred, though there were commercial and some political rights granted to the Christians. The Crusaders withdrew back to Europe soon after.

Baldwin III was King of Jerusalem from 1143 to 1163. He was the eldest son of Queen Melisende and King Fulk. He became king while still a child, and was at first overshadowed by his mother Melisende, whom he eventually defeated in a civil war. During his reign Jerusalem became more closely allied with the Byzantine Empire, and the Second Crusade tried and failed to conquer Damascus. Baldwin captured the important Egyptian fortress of Ascalon, but also had to deal with the increasing power of Nur ad-Din in Syria. He died childless and was succeeded by his brother Amalric.

The Seventh Crusade (1248–1254) was the first of the two Crusades led by Louis IX of France. Also known as the Crusade of Louis IX to the Holy Land, it aimed to reclaim the Holy Land by attacking Egypt, the main seat of Muslim power in the Near East. The Crusade was conducted in response to setbacks in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, beginning with the loss of the Holy City in 1244, and was preached by Innocent IV in conjunction with a crusade against emperor Frederick II, Baltic rebellions and Mongol incursions. After initial success, the crusade ended in defeat, with most of the army – including the king – captured by the Muslims.

The Lordship of Oultrejordain or Oultrejourdain was the name used during the Crusades for an extensive and partly undefined region to the east of the Jordan River, an area known in ancient times as Edom and Moab. It was also referred to as Transjordan.

The siege of Ascalon took place from 25 January to 22 August 1153, in the time period between the Second and Third Crusades, and resulted in the capture of the Fatimid Egyptian fortress by the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Ascalon was an important castle that was used by the Fatimids to launch raids into the Crusader kingdom's territory, and by 1153 it was the last coastal city in Palestine that was not controlled by the Crusaders.

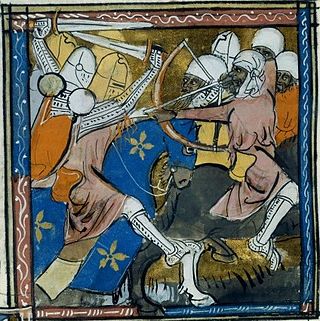

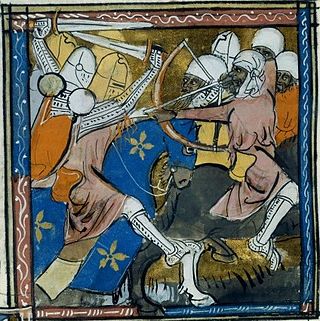

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Christian Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these military expeditions are those to the Holy Land between 1095 and 1291 that had the objective of reconquering Jerusalem and its surrounding area from Muslim rule after the region had been conquered by the Rashidun Caliphate centuries earlier. Beginning with the First Crusade, which resulted in the conquest of Jerusalem in 1099, dozens of military campaigns were organised, providing a focal point of European history for centuries. Crusading declined rapidly after the 15th century with the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans.

Hugh of Fauquembergues, also known as Hugh of St Omer, Hugh of Falkenberg, or Hugh of Falchenberg was Prince of Galilee from 1101 to his death. He was Lord of Fauquembergues before joining the First Crusade. Baldwin I of Jerusalem granted him Galilee after its first prince, Tancred, who was Baldwin's opponent, had voluntarily renounced it. Hugh assisted Baldwin against the Fatimids and made raids into Seljuk territories. He established the castles of Toron and Chastel Neuf. He died fighting against Toghtekin, Atabeg of Damascus.

Niccolò da Poggibonsi was a Franciscan friar of the 14th century who made a famous pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1345–50, which he described in Italian in his Libro d'oltramare.

The History of Jerusalem during the Kingdom of Jerusalem began with the capture of the city by the Latin Christian forces at the apogee of the First Crusade. At that point it had been under Muslim rule for over 450 years. It became the capital of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, until it was again conquered by the Ayyubids under Saladin in 1187. For the next forty years, a series of Christian campaigns, including the Third and Fifth Crusades, attempted in vain to retake the city, until Emperor Frederick II led the Sixth Crusade and successfully negotiated its return in 1229.

The Barons' Crusade (1239–1241), also called the Crusade of 1239, was a crusade to the Holy Land that, in territorial terms, was the most successful crusade since the First Crusade. Called by Pope Gregory IX, the Barons' Crusade broadly embodied the highest point of papal endeavor "to make crusading a universal Christian undertaking." Gregory IX called for a crusade in France, England, and Hungary with different degrees of success. Although the crusaders did not achieve any glorious military victories, they used diplomacy to successfully play the two warring factions of the Ayyubid dynasty against one another for even more concessions than Frederick II had gained during the more well-known Sixth Crusade. For a few years, the Barons' Crusade returned the Kingdom of Jerusalem to its largest size since 1187.

Philip of Ibelin (1180-1227) was a leading nobleman of the Kingdom of Cyprus. As a younger son of Balian of Ibelin and the dowager queen Maria Komnene, he came from the high Crusader nobility of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Stalać Fortress is a historic fortress in the town of Stalać. It is located 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) north of present-day Kruševac, on a hill overlooking the confluence of West and South Morava.

Nompar of Caumont (1391–1446) was a Gascon lord who left written accounts of his pilgrimages to Santiago de Compostela and Jerusalem. His work has also contributed lexicographic inputs to the Dictionary of Middle French.

Pierre de Vieille-Brioude, or Vieille-Bride, was a nobleman from Auvergne who was the eighteenth Grand Master of the Knights Hospitaller between 1240 and 1242, succeeding Bertrand de Comps. He was succeeded by Guillaume de Chateauneuf.

Historical sources of the Crusades: pilgrimages and exploration include those authors whose work describes pilgrimages to the Holy Land and other explorations to the Middle East and Asia that are relevant to Crusader history. In his seminal article in the Catholic Encyclopedia, Dominican friar and historian Bede Jarrett (1881–1934) wrote on the subject of Pilgrimage and identified that the "Crusades also naturally arose out of the idea of pilgrimages." This was reinforced by the Reverend Florentine Stanislaus Bechtel in his article Itineraria in the same encyclopedia. Pilgrims, missionaries, and other travelers to the Holy Land have documented their experiences through accounts of travel and even guides of sites to visit. Many of these have been recognized by historians, for example, the travels of ibn Jubayr and Marco Polo. Some of the more important travel accounts are listed here. Many of these are also of relevance to the study of historical geography and some can be found in the publications of the Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society (PPTS) and Corpus Scriptorum Eccesiasticorum Latinorum (CSEL), particularly CSEL 39, Itinerarium Hierosolymitana. Much of this information is from the seminal work of 19th-century scholars including Edward Robinson, Titus Tobler and Reinhold Röhricht. Recently, the Independent Crusaders Project has been initiated by the Fordham University Center for Medieval Studies providing a database of Crusaders who traveled to the Holy Land independent of military expeditions.

Guillaume de Chateauneuf was the nineteenth Grand Master of the Knights Hospitaller, serving first from 1242–1244 as the successor to Pierre de Vieille-Brioude. He was captured during the Battle of La Forbie in 1244, held hostage in Egypt and ransomed through the Sixth Crusade. During his captivity, his position was filled on an interim basis by Jean de Ronay. De Ronay died in 1250, and de Chateauneuf was released shortly thereafter. He was succeeded by Hugues de Revel.

The theme of recovery of the Holy Land was a genre in High–Late Medieval Christian literature about the Crusades. It consisted of treatises and memoranda on how to recover the Holy Land for Christendom, first appearing in preparation for the Second Council of Lyon in 1274. They proliferated following the loss of Acre in 1291, shortly after which the permanent Crusader presence in the Holy Land came to an end, but mostly disappeared with the cancellation of Philip VI of France's planned crusade in 1336 and the start of the Hundred Years' War between England and France the next year. The high point of recovery proposals was the pontificate of Clement V.

![Bertrandon giving a Latin translation of the Koran to Duke Philip of Burgundy. Illustration (folio 152v) by Jean Le Tavernier [fr] from BnF, MS fr. 9087, made in Lille in 1455. Bertrandon de la Broquiere offers a Koran to Duke Philip.jpg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c1/Bertrandon_de_la_Broqui%C3%A8re_offers_a_Koran_to_Duke_Philip.jpg/220px-Bertrandon_de_la_Broqui%C3%A8re_offers_a_Koran_to_Duke_Philip.jpg)