A composite material is a material which is produced from two or more constituent materials. These constituent materials have notably dissimilar chemical or physical properties and are merged to create a material with properties unlike the individual elements. Within the finished structure, the individual elements remain separate and distinct, distinguishing composites from mixtures and solid solutions.

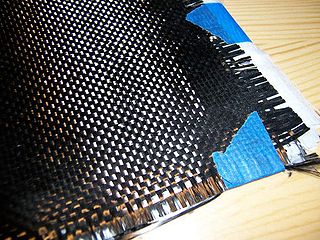

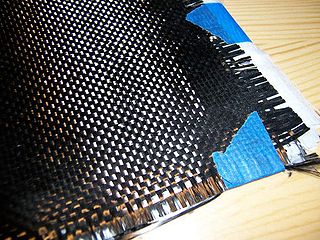

Carbon fibers or carbon fibres are fibers about 5 to 10 micrometers (0.00020–0.00039 in) in diameter and composed mostly of carbon atoms. Carbon fibers have several advantages: high stiffness, high tensile strength, high strength to weight ratio, high chemical resistance, high-temperature tolerance, and low thermal expansion. These properties have made carbon fiber very popular in aerospace, civil engineering, military, motorsports, and other competition sports. However, they are relatively expensive compared to similar fibers, such as glass fiber, basalt fibers, or plastic fibers.

Fiberglass or fibreglass is a common type of fiber-reinforced plastic using glass fiber. The fibers may be randomly arranged, flattened into a sheet called a chopped strand mat, or woven into glass cloth. The plastic matrix may be a thermoset polymer matrix—most often based on thermosetting polymers such as epoxy, polyester resin, or vinyl ester resin—or a thermoplastic.

In materials science, a thermosetting polymer, often called a thermoset, is a polymer that is obtained by irreversibly hardening ("curing") a soft solid or viscous liquid prepolymer (resin). Curing is induced by heat or suitable radiation and may be promoted by high pressure or mixing with a catalyst. Heat is not necessarily applied externally, and is often generated by the reaction of the resin with a curing agent. Curing results in chemical reactions that create extensive cross-linking between polymer chains to produce an infusible and insoluble polymer network.

Lamination is the technique/process of manufacturing a material in multiple layers, so that the composite material achieves improved strength, stability, sound insulation, appearance, or other properties from the use of the differing materials, such as plastic. A laminate is a permanently assembled object created using heat, pressure, welding, or adhesives. Various coating machines, machine presses and calendering equipment are used.

Fibre-reinforced plastic is a composite material made of a polymer matrix reinforced with fibres. The fibres are usually glass, carbon, aramid, or basalt. Rarely, other fibres such as paper, wood, boron, or asbestos have been used. The polymer is usually an epoxy, vinyl ester, or polyester thermosetting plastic, though phenol formaldehyde resins are still in use.

Filament winding is a fabrication technique mainly used for manufacturing open (cylinders) or closed end structures. This process involves winding filaments under tension over a rotating mandrel. The mandrel rotates around the spindle while a delivery eye on a carriage traverses horizontally in line with the axis of the rotating mandrel, laying down fibers in the desired pattern or angle to the rotational axis. The most common filaments are glass or carbon and are impregnated with resin by passing through a bath as they are wound onto the mandrel. Once the mandrel is completely covered to the desired thickness, the resin is cured. Depending on the resin system and its cure characteristics, often the mandrel is autoclaved or heated in an oven or rotated under radiant heaters until the part is cured. Once the resin has cured, the mandrel is removed or extracted, leaving the hollow final product. For some products such as gas bottles, the 'mandrel' is a permanent part of the finished product forming a liner to prevent gas leakage or as a barrier to protect the composite from the fluid to be stored.

A biocomposite is a composite material formed by a matrix (resin) and a reinforcement of natural fibers. Environmental concern and cost of synthetic fibres have led the foundation of using natural fibre as reinforcement in polymeric composites. The matrix phase is formed by polymers derived from renewable and nonrenewable resources. The matrix is important to protect the fibers from environmental degradation and mechanical damage, to hold the fibers together and to transfer the loads on it. In addition, biofibers are the principal components of biocomposites, which are derived from biological origins, for example fibers from crops, recycled wood, waste paper, crop processing byproducts or regenerated cellulose fiber (viscose/rayon). The interest in biocomposites is rapidly growing in terms of industrial applications and fundamental research, due to its great benefits. Biocomposites can be used alone, or as a complement to standard materials, such as carbon fiber. Advocates of biocomposites state that use of these materials improve health and safety in their production, are lighter in weight, have a visual appeal similar to that of wood, and are environmentally superior.

Sheet moulding compound (SMC) or sheet moulding composite is a ready to mould glass-fibre reinforced polyester material primarily used in compression moulding. The sheet is provided in rolls weighing up to 1000 kg. Alternatively the resin and related materials may be mixed on site when a producer wants greater control over the chemistry and filler.

Filler materials are particles added to resin or binders that can improve specific properties, make the product cheaper, or a mixture of both. The two largest segments for filler material use is elastomers and plastics. Worldwide, more than 53 million tons of fillers are used every year in application areas such as paper, plastics, rubber, paints, coatings, adhesives, and sealants. As such, fillers, produced by more than 700 companies, rank among the world's major raw materials and are contained in a variety of goods for daily consumer needs. The top filler materials used are ground calcium carbonate (GCC), precipitated calcium carbonate (PCC), kaolin, talc, and carbon black. Filler materials can affect the tensile strength, toughness, heat resistance, color, clarity, etc. A good example of this is the addition of talc to polypropylene. Most of the filler materials used in plastics are mineral or glass based filler materials. Particulates and fibers are the main subgroups of filler materials. Particulates are small particles of filler that are mixed in the matrix where size and aspect ratio are important. Fibers are small circular strands that can be very long and have very high aspect ratios.

Fiber volume ratio is an important mathematical element in composite engineering. Fiber volume ratio, or fiber volume fraction, is the percentage of fiber volume in the entire volume of a fiber-reinforced composite material. When manufacturing polymer composites, fibers are impregnated with resin. The amount of resin to fiber ratio is calculated by the geometric organization of the fibers, which affects the amount of resin that can enter the composite. The impregnation around the fibers is highly dependent on the orientation of the fibers and the architecture of the fibers. The geometric analysis of the composite can be seen in the cross-section of the composite. Voids are often formed in a composite structure throughout the manufacturing process and must be calculated into the total fiber volume fraction of the composite. The fraction of fiber reinforcement is very important in determining the overall mechanical properties of a composite. A higher fiber volume fraction typically results in better mechanical properties of the composite.

Three-dimensional composites use fiber preforms constructed from yarns or tows arranged into complex three-dimensional structures. These can be created from a 3D weaving process, a 3D knitting process, a 3D braiding process, or a 3D lay of short fibers. A resin is applied to the 3D preform to create the composite material. Three-dimensional composites are used in highly engineered and highly technical applications in order to achieve complex mechanical properties. Three-dimensional composites are engineered to react to stresses and strains in ways that are not possible with traditional composite materials composed of single direction tows, or 2D woven composites, sandwich composites or stacked laminate materials.

In materials science, advanced composite materials (ACMs) are materials that are generally characterized by unusually high strength fibres with unusually high stiffness, or modulus of elasticity characteristics, compared to other materials, while bound together by weaker matrices. These are termed "advanced composite materials" in comparison to the composite materials commonly in use such as reinforced concrete, or even concrete itself. The high strength fibers are also low density while occupying a large fraction of the volume.

Tailored fiber placement (TFP) is a textile manufacturing technique based on the principle of sewing for a continuous placement of fibrous material for composite components. The fibrous material is fixed with an upper and lower stitching thread on a base material. Compared to other textile manufacturing processes fiber material can be placed near net-shape in curvilinear patterns upon a base material in order to create stress adapted composite parts.

A void or a pore is three-dimensional region that remains unfilled with polymer and fibers in a composite material. Voids are typically the result of poor manufacturing of the material and are generally deemed undesirable. Voids can affect the mechanical properties and lifespan of the composite. They degrade mainly the matrix-dominated properties such as interlaminar shear strength, longitudinal compressive strength, and transverse tensile strength. Voids can act as crack initiation sites as well as allow moisture to penetrate the composite and contribute to the anisotropy of the composite. For aerospace applications, a void content of approximately 1% is still acceptable, while for less sensitive applications, the allowance limit is 3-5%. Although a small increase in void content may not seem to cause significant issues, a 1-3% increase in void content of carbon fiber reinforced composite can reduce the mechanical properties by up to 20%

Thermoplastics containing short fiber reinforcements were first introduced commercially in the 1960s. The most common type of fibers used in short fiber thermoplastics are glass fiber and carbon fiber . Adding short fibers to thermoplastic resins improves the composite performance for lightweight applications. In addition, short fiber thermoplastic composites are easier and cheaper to produce than continuous fiber reinforced composites. This compromise between cost and performance allows short fiber reinforced thermoplastics to be used in myriad applications.

Carbon fiber testing is a set of various different tests that researchers use to characterize the properties of carbon fiber. The results for the testing are used to aid the manufacturer and developers decisions selecting and designing material composites, manufacturing processes and for ensured safety and integrity. Safety-critical carbon fiber components, such as structural parts in machines, vehicles, aircraft or architectural elements are subject to testing.

Transfer molding is a manufacturing process in which casting material is forced into a mold. Transfer molding is different from compression molding in that the mold is enclosed rather than open to the fill plunger resulting in higher dimensional tolerances and less environmental impact. Compared to injection molding, transfer molding uses higher pressures to uniformly fill the mold cavity. This allows thicker reinforcing fiber matrices to be more completely saturated by resin. Furthermore, unlike injection molding the transfer mold casting material may start the process as a solid. This can reduce equipment costs and time dependency. The transfer process may have a slower fill rate than an equivalent injection molding process.

CFSMC, or Carbon Fiber Sheet Molding Compound, is a ready to mold carbon fiber reinforced polymer composite material used in compression molding. While traditional SMC utilizes chopped glass fibers in a polymer resin, CFSMC utilizes chopped carbon fibers. The length and distribution of the carbon fibers is more regular, homogeneous, and constant than the standard glass SMC. CFSMC offers much higher stiffness and usually higher strength than standard SMC, but at a higher cost.

In materials science, a polymer matrix composite (PMC) is a composite material composed of a variety of short or continuous fibers bound together by a matrix of organic polymers. PMCs are designed to transfer loads between fibers of a matrix. Some of the advantages with PMCs include their light weight, high resistance to abrasion and corrosion, and high stiffness and strength along the direction of their reinforcements.