Related Research Articles

Racism is discrimination and prejudice against people based on their race or ethnicity. Racism can be present in social actions, practices, or political systems that support the expression of prejudice or aversion in discriminatory practices. The ideology underlying racist practices often assumes that humans can be subdivided into distinct groups that are different in their social behavior and innate capacities and that can be ranked as inferior or superior. Racist ideology can become manifest in many aspects of social life. Associated social actions may include nativism, xenophobia, otherness, segregation, hierarchical ranking, supremacism, and related social phenomena. Racism refers to violation of racial equality based on equal opportunities or based on equality of outcomes for different races or ethnicities, also called substantive equality.

Racial segregation is the separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, such as schools and hospitals by people of different races. Specifically, it may be applied to activities such as eating in restaurants, drinking from water fountains, using public toilets, attending schools, going to films, riding buses, renting or purchasing homes or renting hotel rooms. In addition, segregation often allows close contact between members of different racial or ethnic groups in hierarchical situations, such as allowing a person of one race to work as a servant for a member of another race. Racial segregation has generally been outlawed worldwide.

White supremacy is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White supremacy has roots in the now-discredited doctrine of scientific racism and was a key justification for European colonialism.

Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd, also known as H. F. Verwoerd, was a Dutch-born South African politician, scholar, and newspaper editor who was Prime Minister of South Africa and is commonly regarded as the architect of apartheid and nicknamed the "father of apartheid". Verwoerd played a significant role in socially engineering apartheid, the country's system of institutionalized racial segregation and white supremacy, and implementing its policies, as Minister of Native Affairs (1950–1958) and then as prime minister (1958–1966). Furthermore, Verwoerd played a vital role in helping the far-right National Party come to power in 1948, serving as their political strategist and propagandist, becoming party leader upon his premiership. He was the Union of South Africa's last prime minister, from 1958 to 1961, when he proclaimed the founding of the Republic of South Africa, remaining its prime minister until his assassination in 1966.

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscientific belief that the human species can be subdivided into biologically distinct taxa called "races", and that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism, racial inferiority, or racial superiority. Before the mid-20th century, scientific racism was accepted throughout the scientific community, but it is no longer considered scientific. The division of humankind into biologically separate groups, along with the assignment of particular physical and mental characteristics to these groups through constructing and applying corresponding explanatory models, is referred to as racialism, race realism, or race science by those who support these ideas. Modern scientific consensus rejects this view as being irreconcilable with modern genetic research.

The Department of Bantu Education was an organization created by the National Party of South Africa in 1953. The Bantu Education Act, 1953 provided the legislative framework for this department.

The Bantu Education Act 1953 was a South African segregation law that legislated for several aspects of the apartheid system. Its major provision enforced racially-separated educational facilities; Even universities were made "tribal", and all but three missionary schools chose to close down when the government would no longer help to support their schools. Very few authorities continued using their own finances to support education for native Africans. In 1959, that type of education was extended to "non-white" universities and colleges with the Extension of University Education Act, 1959, and the University College of Fort Hare was taken over by the government and degraded to being part of the Bantu education system. It is often argued that the policy of Bantu (African) education was aimed to direct black or non-white youth to the unskilled labour market although Hendrik Verwoerd, the Minister of Native Affairs, claimed that the aim was to solve South Africa's "ethnic problems" by creating complementary economic and political units for different ethnic groups. A particular fear of the National Party that most likely led to the passing of this legislation was the rising number of children joining urban gangs.

The Carnegie Corporation of New York is a philanthropic fund established by Andrew Carnegie in 1911 to support education programs across the United States, and later the world.

Apartheid was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was characterised by an authoritarian political culture based on baasskap, which ensured that South Africa was dominated politically, socially, and economically by the nation's minority white population. In this minoritarian system, there was social stratification and campaigns of marginalization such that white citizens had the highest status, with them being followed by Indians as well as Coloureds and then Black Africans. The economic legacy and social effects of apartheid continue to the present day, particularly inequality.

Racial steering refers to the practice in which real estate brokers guide prospective home buyers towards or away from certain neighborhoods based on their race. The term is used in the context of de facto residential segregation in the United States, and is often divided into two broad classes of conduct:

- Advising customers to purchase homes in particular neighborhoods on the basis of race.

- Failing, on the basis of race, to show, or to inform buyers of homes that meet their specifications.

Facilities and services such as housing, healthcare, education, employment, and transportation have been systematically separated in the United States based on racial categorizations. Segregation was the legally or socially enforced separation of African Americans from whites, as well as the separation of other ethnic minorities from majority and mainstream communities. While mainly referring to the physical separation and provision of separate facilities, it can also refer to other manifestations such as prohibitions against interracial marriage, and the separation of roles within an institution. The U.S. Armed Forces were formally segregated until 1948, as black units were separated from white units but were still typically led by white officers.

Reverse racism, sometimes referred to as reverse discrimination, is the concept that affirmative action and similar color-conscious programs for redressing racial inequality are forms of anti-white racism. The concept is often associated with conservative social movements and reflects a belief that social and economic gains by Black people and other people of color cause disadvantages for white people.

The African-American middle class consists of African-Americans who have middle-class status within the American class structure. It is a societal level within the African-American community that primarily began to develop in the early 1960s, when the ongoing Civil Rights Movement led to the outlawing of de jure racial segregation. The African American middle class exists throughout the United States, particularly in the Northeast and in the South, with the largest contiguous majority black middle-class neighborhoods being in the Washington, DC suburbs in Maryland. The African American middle class is also prevalent in the Atlanta, Charlotte, Houston, Dallas, Los Angeles, New Orleans, New York, San Antonio and Chicago areas.

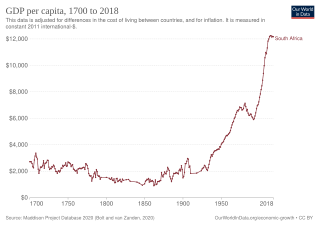

Prior to the arrival of the European settlers in the 17th century the economy of what was to become South Africa was dominated by subsistence agriculture and hunting.

Negotiations to end apartheid began in 1990 and continued until President Nelson Mandela's electoral victory as South Africa's first Black president in the first democratic all-races general election of 1994. This signified the legislative end of apartheid in South Africa, a system of widespread racially-based segregation to enforce almost complete separation of white and Black races in South Africa. Before the legislative end of apartheid, whites had held almost complete control over all political and socioeconomic power in South Africa during apartheid, only allowing acquiescent Black traditional leaders to participate in facades of political power. Repercussions from the decades of apartheid continue to resonate through every facet of South African life, despite copious amounts of legislation meant to alleviate inequalities.

Laissez-faire racism is closely related to color blindness and covert racism, and is theorised to encompass an ideology that blames minorities for their poorer economic situations, viewing it as the result of cultural inferiority. The term is used largely by scholars of whiteness studies, who argue that laissez-faire racism has tangible consequences even though few would openly claim to be, or even believe they are, laissez-faire racists.

In the United States, housing segregation is the practice of denying African Americans and other minority groups equal access to housing through the process of misinformation, denial of realty and financing services, and racial steering. Housing policy in the United States has influenced housing segregation trends throughout history. Key legislation include the National Housing Act of 1934, the G.I. Bill, and the Fair Housing Act. Factors such as socioeconomic status, spatial assimilation, and immigration contribute to perpetuating housing segregation. The effects of housing segregation include relocation, unequal living standards, and poverty. However, there have been initiatives to combat housing segregation, such as the Section 8 housing program.

Racism in South Africa can be traced back to the earliest historical accounts of interactions between African, Asian, and European peoples along the coast of Southern Africa. It has existed throughout several centuries of the history of South Africa, dating back to the Dutch colonization of Southern Africa, which started in 1652. Before universal suffrage was achieved in 1994, White South Africans, especially Afrikaners during the period of Apartheid, enjoyed various legally or socially sanctioned privileges and rights that were denied to the indigenous African peoples. Examples of systematic racism over the course of South Africa's history include forced removals, racial inequality and segregation, uneven resource distribution, and disenfranchisement. Racial controversies and politics remain major phenomena in the country.

In the United States, racial inequality refers to the social inequality and advantages and disparities that affect different races. These can also be seen as a result of historic oppression, inequality of inheritance, or racism and prejudice, especially against minority groups.

The Tomlinson Report was a 1954 report released by the Commission for the Socioeconomic Development of the Bantu Areas, known as the Tomlinson Commission, that was commissioned by the South African government to study the economic viability of the native reserves. These reserves were intended to serve as the homelands for the black population. The report is named for Frederick R. Tomlinson, professor of agricultural economics at the University of Pretoria. Tomlinson chaired the ten-person commission, which was established in 1950. The Tomlinson Report found that the reserves were incapable of containing South Africa's black population without significant state investment. However, Hendrik Verwoerd, Minister of Native Affairs, rejected several recommendations in the report. While both Verwoerd and the Tomlinson Commission believed in "separate development" for the reserves, Verwoerd did not want to end economic interdependence between the reserves and industries in white-controlled areas. The government would go on to pass legislation to restrict the movement of blacks who lived in the reserves to white-controlled areas.

References

- ↑ "First Inquiry Into Poverty". Carnegie Corporation Oral History Project . Columbia University Libraries. 2006.

- ↑ Roos, Neil (2003). "The Second World War, the Army Education Scheme and the 'Discipline' of the White Poor in South Africa". History of Education: Journal of the History of Education Society . 32 (6): 645–659. doi:10.1080/0046760032000151474. S2CID 145424883.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Füredi, Frank (1998). The Silent War: Imperialism and the Changing Perception of Race. New Brunswich, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. pp. 66–67. ISBN 0-8135-2612-4.

- 1 2 Slater, David; Taylor, Peter James (1999). The American Century: Consensus and Coercion in the Projection of American Power. Wiley. p. 290. ISBN 0-631-21222-1.

- 1 2 Stoler, Ann Laura, ed. (2006). Haunted by Empire: Geographies of Intimacy in North American History. Duke University Press. p. 66. ISBN 0-8223-3724-X.

- ↑ Verbeek, Jennifer (1986). "Racially segregated school libraries in KwaZulu/Natal, South Africa". Journal of Librarianship and Information Science. 18 (1): 23–46. doi:10.1177/096100068601800102. S2CID 62204622.

- 1 2 Dubow, Saul (1995). Scientific Racism in Modern South Africa . Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-47907-X.