Chicago literature is writing, primarily by writers born or living in Chicago, that reflects the culture of the city.

Chicago literature is writing, primarily by writers born or living in Chicago, that reflects the culture of the city.

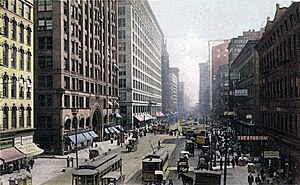

James Atlas, in his biography of Chicago writer Saul Bellow, suggests that "the city's reputation for nurturing literary and intellectual talent can be traced to the same geographical centrality that made it a great industrial power." [1] When Chicago was incorporated in 1837, it was a frontier outpost with about 4,000 people. The population rose rapidly to approximately 100,000 in 1860. By 1890, the city had over 1 million people. [2] Chicago's dynamic growth, as well as the manufacturing, economics, and politics that fueled this growth, can be seen in the works of writers like Carl Sandburg, Theodore Dreiser, Sherwood Anderson, Hamlin Garland, Frank Norris, Upton Sinclair, Willa Cather, and Edna Ferber. [3]

Due to these rapid changes, Chicago writers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries faced the challenge of how to depict this potentially disorienting new urban reality. Narrative fiction of that time, much of it in the style of "high-flown romance" and "genteel realism", needed a new approach to describe Chicago's social, political, and economic conditions. [4] Chicagoans worked hard to create a literary tradition that would stand the test of time, [5] and create a "city of feeling" out of concrete, steel, vast lake, and open prairie. [6] Among the new techniques and styles embraced by Chicago writers were "naturalism", "imagism", and "free verse". [3] Themes often centered on an exciting but dirty urbanism, as well as the quaint but dark and sometimes stultifying small town.

Chicago's early twentieth-century writers and publishers were seen as producing innovative work that broke with the literary traditions of Europe and the Eastern United States. In 1920, the critic H. L. Mencken wrote in a London magazine, TheNation , that Chicago was the "Literary Capital of the United States". [7] Expressing the attitude that Chicago writers were creating a distinctive, new, and far from genteel literary idiom, he wrote, "Find a writer who is indubitably an American in every pulse-beat, snort, and adenoid, an American who has something new and peculiarly American to say and who says it in an unmistakable American way, and nine times out of ten you will find that he has some sort of connection with the gargantuan and inordinate abattoir by Lake Michigan." [8]

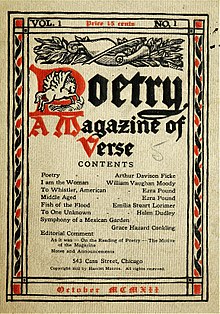

While Chicago produced much realist and naturalist fiction, [9] its literary institutions also played a crucial role in promoting international modernism. The avant-garde Little Review (founded 1914 by Margaret Anderson) began in Chicago, though it later moved elsewhere. The Little Review provided an important platform for experimental literature, famously it was the first to publish James Joyce's novel Ulysses, in serial form until the magazine was forced to discontinue the novel due to obscenity charges. [10] Similarly, the publication that became Poetry magazine (founded 1912 by Harriet Monroe) was instrumental in launching the Imagist and Objectivist poetic movements. [11] T. S. Eliot's first professionally published poem, "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock", appeared in Poetry. Contributors have included Ezra Pound, W. B. Yeats, William Carlos Williams, Langston Hughes and Carl Sandburg, among others. The magazine also discovered such poets as Gwendolyn Brooks, James Merrill, and John Ashbery. [12] Poetry and the Little Review were "daring" in their editorial championship of the modernist movement. Later editors also made substantial contributions in poetry, as did Chicago's university and performance venues. [13]

Chicago's universities also have a strong reputation for developing literary talent. In the second half of the 20th century, the University of Chicago served as a hub for many emerging postmodern writers such as Saul Bellow, Kurt Vonnegut, Philip Roth, and Robert Coover. Bellow received his Bachelor's from nearby Northwestern University, which has also produced acclaimed authors such as George R.R. Martin, Tina Rosenberg and Kate Walbert.

Today, Chicago is home to the world's largest youth poetry festival, Louder Than a Bomb. [14] [15] Since its founding in 2001, Louder Than a Bomb has grown into a multi-week celebration that includes competitions, workshops, and other poetry-related events. By 2018, the festival was drawing over 100 teams for a total of more than 1000 young poets competing in spoken word tournaments. The festival is credited with influencing contemporary Chicago poets like Nate Marshall and José Olivarez. [14]

According to Bill Savage in The Encyclopedia of Chicago, today's Chicago writers are still interested in the same social themes and urban landscapes that compelled earlier Chicago writers: "the fundamental dilemmas presented by city life in general and by the specifics of Chicago's urban spaces, history, and relentless change." [16]

The Encyclopedia of Chicago identifies three periods of works from Chicago which had a major influence on American Literature: [17]

Literature scholar Robert Bone argues for the existence of an overlapping fourth period:

Much notable Chicago writing focuses on the city itself, with social criticism keeping exultation in check. Here is a selection of Chicago's most famous works about itself:

Alternative versions of Chicago sometimes appear in fantasy and science fiction novels.

Other noted writers, who were from Chicago or who spent a significant amount of their careers in Chicago include, David Mamet, Ernest Hemingway, Ben Hecht, John Dos Passos, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Edgar Lee Masters, Sherwood Anderson, Eugene Field, and Hamlin Garland.