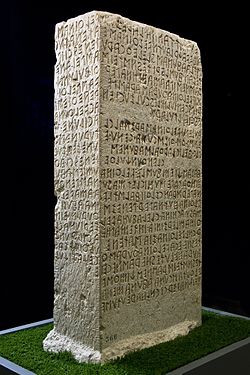

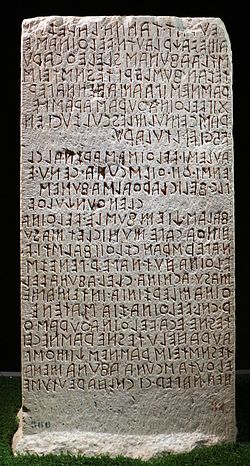

Formatted according to latest theory by F. Roncalli for the original lines, distorted when they were copied onto this stone. [4] There are no capital letters in the original, but known and certain names are capitalized below. Line numbers in parentheses indicate those of the actual cippus. Word spacing is mostly hypothetical.

Notes

The last word in the text, ziχuχe means "was written". [6]

In line 10, θi-i and θi-l are respectively dative/instrumental and genitive for "water," and according to Facchetti (and approved by Wylin) the form cenu means "(is) obtained." Wylin translates the phrase (9-11) Aulesi Velθinas Arznal clensi/ θii θil ścuna cenu e/pl-c feli-c Larθal-ś Afun-e as "'With respect to the water of Aule Velthina, son of Arznei, the use (ścuna) of water is obtained bothepl and feli by Larth Afuna." And Wylin points out that the tricolon in lines 33-34 acilune. turune. ścune probably corresponds to the Latin legal phrase facere, dare, praestare "to do, to give, and to make good," a phrase used with respect to personal obligations rather than legal rights." [2] [7] [8]

Some phrases identified and partly translated by van Heems include: (1-2) eurat tanna larezul ame --"Larezul is the arbitrator tanna (of what follows?)"; (2-3) vaχr lautn Velθinaś eśtla Afunas slel eθ caru -- "An agreement of the Velthina tribe with that of Afuna, by his own (accord) was concluded (car-u ?)"; (3-5) tezan fuśle-ri tesnś-teiś raśneś -- "Complying (tezan ?) to the ordinances (fuśle-ri ?) from the public/Etruscan law"; (5-7) ipa ama hen naper XII Velθina-θur-aś araś peraś-c -- "that 12 hen (arable?) acres of Velthinas shall be dedicated and pera -ed." (18-21) inte mamer cnl Velθina zia śatene tesne, eca Velθina θuraś θaura helu --"To the (tomb) which Velthina zi-ed on the mamer according to the satena law, this has been hel -ed as the tomb of Velthina". In lines 29–30, the form fulumχva mirrors pulumχva in the Pyrgi Tablets and (in the singular?) pulum in the inscription on the Golini Tomb. (36-46)aθumicś Afunaś. penθna. ama. Velθina. Afuna θuruni. ein zeriuna. cla. θil. θunχulθl. iχ. ca ceχa. ziχuχe -- "The cippus of Afuna is aθumicś. Velthina (and) Afuna together (θuruni ?) shall not zerina (violate?) the accord concernting the water (rights), as this is written above." [9]