Iranian Georgians or Persian Georgians are Iranian citizens who are ethnically Georgian, and are an ethnic group living in Iran. Today's Georgia was a subject of Iran in ancient times under the Achaemenid and Sassanian empires and from the 16th century till the early 19th century, starting with the Safavids in power and later Qajars. Shah Abbas I, his predecessors, and successors, relocated by force hundreds of thousands of Christian, and Jewish Georgians as part of his programs to reduce the power of the Qizilbash, develop industrial economy, strengthen the military, and populate newly built towns in various places in Iran including the provinces of Isfahan, Mazandaran and Khuzestan. A certain number of these, among them members of the nobility, also migrated voluntarily over the centuries, as well as some that moved as muhajirs in the 19th century to Iran, following the Russian conquest of the Caucasus. The Georgian community of Fereydunshahr have retained their distinct Georgian identity to this day, despite adopting certain aspects of Iranian culture such as the Persian language.

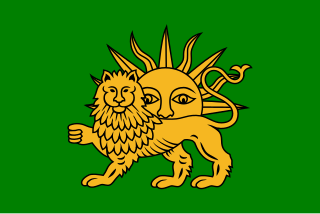

The Safavid dynasty was one of Iran's most significant ruling dynasties reigning from 1501 to 1736. Their rule is often considered the beginning of modern Iranian history, as well as one of the gunpowder empires. The Safavid Shāh Ismā'īl I established the Twelver denomination of Shīʿa Islam as the official religion of the Persian Empire, marking one of the most important turning points in the history of Islam. The Safavid dynasty had its origin in the Safavid order of Sufism, which was established in the city of Ardabil in the Iranian Azerbaijan region. It was an Iranian dynasty of Kurdish origin, but during their rule they intermarried with Turkoman, Georgian, Circassian, and Pontic Greek dignitaries, nevertheless, for practical purposes, they were Turkish-speaking and Turkified. From their base in Ardabil, the Safavids established control over parts of Greater Iran and reasserted the Iranian identity of the region, thus becoming the first native dynasty since the Sasanian Empire to establish a national state officially known as Iran.

Abbas I, commonly known as Abbas the Great, was the fifth Safavid shah of Iran from 1588 to 1629. The third son of Shah Mohammad Khodabanda, he is generally considered one of the most important rulers in Iranian history and the greatest ruler of the Safavid dynasty.

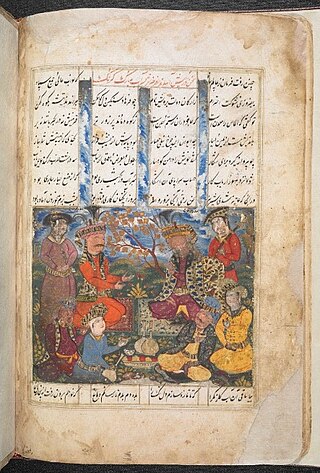

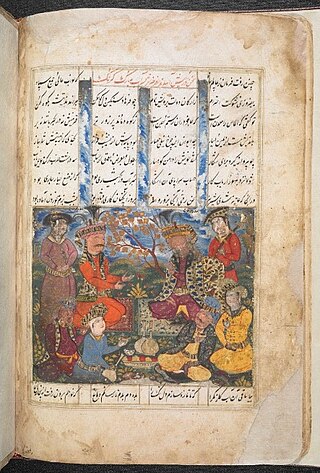

Tahmasp I was the second shah of Safavid Iran from 1524 until his death in 1576. He was the eldest son of Shah Ismail I and his principal consort, Tajlu Khanum.

Qizilbash or Kizilbash were a diverse array of mainly Turkoman Shia militant groups that flourished in Azerbaijan, Anatolia, the Armenian highlands, the Caucasus from the late 15th century onwards, and contributed to the foundation of the Safavid dynasty in early modern Iran.

Sam Mirza, known by his dynastic name of Shah Safi, was the sixth shah of Safavid Iran, ruling from 1629 to 1642. Abbas the Great was succeeded by his grandson, Safi. A reclusive and passive character, Safi was unable to fill the power vacuum which his grandfather had left behind. His officials undermined his authority and revolts constantly broke out across the realm. The continuing war with the Ottoman Empire, started with initial success during Abbas the Great's reign, but ended with the defeat of Iran and the Treaty of Zuhab, which returned much of Iran's conquests in Mesopotamia to the Ottomans.

Mohammad Khodabanda, was the fourth Safavid shah of Iran from 1578 until his overthrow in 1587 by his son Abbas I. Khodabanda had succeeded his brother, Ismail II. Khodabanda was the son of Shah Tahmasp I by a Turcoman mother, Sultanum Begum Mawsillu, and grandson of Ismail I, founder of the Safavid dynasty.

Abbas II was the seventh Shah of Safavid Iran, ruling from 1642 to 1666. As the eldest son of Safi and his Circassian wife, Anna Khanum, he inherited the throne when he was nine, and had to rely on a regency led by Saru Taqi, the erstwhile grand vizier of his father, to govern in his place. During the regency, Abbas received formal kingly education that, until then, he had been denied. In 1645, at age fifteen, he was able to remove Saru Taqi from power, and after purging the bureaucracy ranks, asserted his authority over his court and began his absolute rule.

Allahverdi Khan was an Iranian general and statesman of Georgian origin who, initially a gholām, rose to high office in the Safavid state.

The Undiladze family was a Georgian noble family whose members rose in prominence in the service of Safavid Iran and dominated the Shah’s court at a certain period of the late 16th and early 17th centuries.

The Ottoman–Persian War (1578–1590) or Ottoman–Iranian War of 1578–1590 was one of the many wars between the neighboring arch rivals of Safavid Empire and the Ottoman Empire.

The Guarded Domains of Iran, commonly called Safavid Iran, Safavid Persia or the Safavid Empire, was one of the largest and longest-lasting Iranian empires. It was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often considered the beginning of modern Iranian history, as well as one of the gunpowder empires. The Safavid Shāh Ismā'īl I established the Twelver denomination of Shīʿa Islam as the official religion of the empire, marking one of the most important turning points in the history of Islam.

Ganj Ali Khan was a military officer in Safavid Iran, who served as governor in various provinces and was known for his loyal service to king (shah) Abbas I. Ganj Ali Khan continuously aided the shah on almost all of his military campaigns until his own death in 1624/5. He was also a great builder, the Ganjali Khan Complex being one of his finest achievements.

The military of Safavid Iran covers the military history of Safavid Iran from 1501 to 1736.

Mohammad Baqer Mirza better known in the West as Safi Mirza was the oldest son of Shah Abbas the Great, and the crown prince of the Safavid dynasty during Abbas' reign and his own short life.

Haydar Mirza Safavi was a Safavid prince who declared himself as the king (shah) of Iran on 15 May 1576, the day after his father Tahmasp I had died. He was, however, killed that same day by the Qizilbash tribes that favoured his brother Ismail Mirza Safavi as the successor of their father. His mother was Sultanzadeh Khanum, a Georgian lady.

Sultan-Agha Khanum also in Western sources Corasi was a Safavid queen consort of Kumyk origin, as the second wife of Safavid king Tahmasp I.

The province of Georgia was a velayat (province) of Safavid Iran located in the area of present-day Georgia. The territory of the province was principally made up of the two subordinate eastern Georgian kingdoms of Kartli and Kakheti and, briefly, parts of the Principality of Samtskhe. The city of Tiflis was its administrative center, the base of Safavid power in the province, and the seat of the rulers of Kartli. It also housed an important Safavid mint.

Anna Khanum was the consort of the Safavid king Safi. She was the mother of her husband's successor, King Abbas II.

Nakihat Khanum was the first consort of the Safavid king (shah) Abbas II.