Response

| | This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (November 2019) |

The Confiscation Acts were laws passed by the United States Congress during the Civil War with the intention of freeing the slaves still held by the Confederate forces in the South.

The Confiscation Act of 1861 authorized the confiscation of any Confederate property by Union forces ("property" included slaves). This meant that all slaves that fought or worked for the Confederate military were confiscated whenever court proceedings "condemned" them as property used to support the rebellion. The bill passed in the United States House of Representatives 60–48 and in the Senate 24–11. [1] The act was signed into law by President Lincoln on August 6, 1861. [2]

The Confiscation Act of 1862 was passed on July 17, 1862. It stated that any Confederate official, military or civilian, who did not surrender within 60 days of the act's passage would have their slaves freed in criminal proceedings. However, this act was only applicable to Confederate areas that had already been occupied by the Union Army.

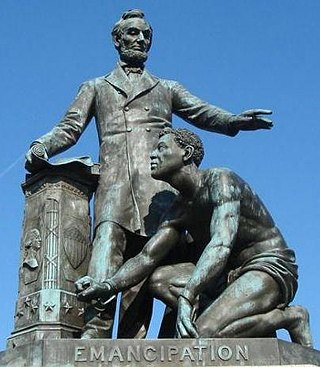

Though U.S. President Abraham Lincoln was concerned about the practical legality of these acts and believed that they might push the border states towards siding with the Confederacy, he nonetheless signed them into law. The growing movement towards emancipation was aided by these acts, which were followed by the Preliminary and Final Emancipation Proclamations of September 1862 and January 1863.

"The Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861, jolted Congress into a realization that the Civil War might not be the swift, neat confrontation they hoped for – and that disunionists might need to be held legally liable for their actions. Lincoln biographer John Torrey Morse, Jr. wrote, "The Northern armies ran against slavery immediately.... [T]housands of slaves at Manassas were doing the work of laborers and servants, and rendering all the whites of the Southern army available for fighting. The handicap was so severe and obvious, that it immediately provoked the introduction of a bill freeing slaves belonging to rebels and used for carrying on the war." [3]

"In the first summer of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln called the Thirty-seventh United States Congress into special session on July 4, 1861. On August 6, the last day of this short first session, Congress passed and Lincoln signed the First Confiscation Act. This law authorized the federal government to seize the property of all those participating directly in rebellion. Enacted in the wake of the first battle of Bull Run, this hurriedly passed law did not break much new ground. It was essentially a restatement of internationally recognized laws of war and authorized the seizure of any property, including slave property, used by the Confederacy to directly aid the war effort."

When the second session of the Thirty-seventh Congress convened in December 1861, public pressure was mounting in the North for another, more vigorous confiscation bill. Senator Lyman Trumbull, a Republican from Illinois and the chairman of the Judiciary Committee, quickly emerged as the most important figure on confiscation. On December 2, 1861, Trumbull took the floor to introduce a new confiscation bill. This bill envisioned the seizure of all rebel property, whether used directly to support the war, or owned by a rebel a thousand miles away from any battlefield.

After several months of debate, Congress came to a stalemate over the confiscation of rebel property. This paralysis was not the result of incompetence, or because confiscation was considered relatively unimportant; it was instead an issue of ideological differences debated by a country in the midst of war. The debate, to the surprise and ultimate frustration of the legislators themselves, reflected deep-seated, nearly intractable divisions over the social role of property and the extent of sovereign power over property in American law and the Constitution.

Within a few weeks of the introduction of Trumbull's bill, different ideological coalitions emerged. Trumbull took the lead of a group of radicals sponsoring a vigorous confiscation bill, joined by Charles Sumner of Massachusetts and Benjamin Wade of Ohio in the Senate and George Julian of Indiana in the House. To their amazement these confiscation radicals soon faced bitter opposition both from outside and from within their own Republican Party. A group of conservatives soon began to condemn the radical bill as a violation of the Fifth Amendment and the Constitution's prohibition of bills of attainder. Republican senator Orville Browning of Illinois, a powerful friend of President Lincoln, led these conservatives in condemning the radical confiscation plan. As winter turned to spring and spring to summer, Congress argued endlessly over confiscation. Was property confiscation a legitimate power of the national legislature? Was confiscation in violation of the Constitution? Were slaves a type of property subject to confiscation? These basic questions drew intense scrutiny and the congressional debates were remarkable for their sustained consideration, in the midst of war, of the power of government and the rights of property.

Between these two warring camps, a group of confiscation moderates brokered a compromise bill that, unfortunately, proved mostly unworkable. These moderates were led by John Sherman of Ohio, Daniel Clark of New Hampshire, and Henry Wilson of Massachusetts in the Senate, and Republican Thomas D. Eliot of Massachusetts in the House. The moderates sent Trumbull's bill to a select committee, where they reworked it into a much less radical bill providing a much greater role for the judiciary than the radicals wanted. On July 17, President Lincoln signed the Second Confiscation Act into law, after first insisting that Congress pass an "explanatory resolution" to the act. This resolution reflected President Lincoln's concern that permanent property confiscation was a "corruption of blood" prohibited by the Constitution and provided that property seized from individual offenders under the act could not be seized beyond the lifetime of the offender. President Lincoln had fully intended to veto the bill if Congress did not pass his resolution, and in an effort to ensure his objections were an official part of the congressional record, after signing the bill he also sent the veto message he had prepared to Congress." [4]

The First Confiscation Act, signed into law on August 6, 1861 stated that:

The Second Confiscation Act was signed into law on July 17, 1862 and contained provisions such as:

The Union Army was given primary control over implementation of the acts. However, Congress reached a stalemate that impeded the implementation of these Acts.[ citation needed ]

| | This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (November 2019) |

"Essentially, the Confiscation Act of 1862 prepared the way for the Emancipation Proclamation and solved the immediate dilemma facing the army concerning the status of slave," [6] even though the act was not heavily enforced [ citation needed ].

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War, defending the nation as a constitutional union, defeating the Confederacy, playing a major role in the abolition of slavery, expanding the power of the federal government, and modernizing the U.S. economy.

The American Civil War was a civil war in the United States between the Union and the Confederacy, which was formed in 1861 by states that had seceded from the Union. The central conflict leading to war was a dispute over whether slavery should be permitted to expand into the western territories, leading to more slave states, or be prohibited from doing so, which many believed would place slavery on a course of ultimate extinction.

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War. The Proclamation had the effect of changing the legal status of more than 3.5 million enslaved African Americans in the secessionist Confederate states from enslaved to free. As soon as slaves escaped the control of their enslavers, either by fleeing to Union lines or through the advance of federal troops, they were permanently free. In addition, the Proclamation allowed for former slaves to "be received into the armed service of the United States". The Emancipation Proclamation played a significant part in the end of slavery in the United States.

The Reconstruction era was a period in United States history and Southern United States history that followed the American Civil War and was dominated by the legal, social, and political challenges of the abolition of slavery and the reintegration of the eleven former Confederate States of America into the United States. During this period, three amendments were added to the United States Constitution to grant citizenship and equal civil rights to the newly freed slaves. To circumvent these legal achievements, the former Confederate states imposed poll taxes and literacy tests and engaged in terrorism to intimidate and control black people and to discourage or prevent them from voting.

Benjamin Franklin "Bluff" Wade was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States Senator for Ohio from 1851 to 1869. He is known for his leading role among the Radical Republicans. Had the 1868 impeachment of U.S. President Andrew Johnson led to a conviction in the Senate, as president pro tempore of the U.S. Senate, Wade would have become acting president for the remaining nine months of Johnson's term.

In the American Civil War (1861–65), the border states or the Border South were four, later five, slave states in the Upper South that primarily supported the Union. They were Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri, and after 1863, the new state of West Virginia. To their north they bordered free states of the Union, and all but Delaware bordered slave states of the Confederacy to their south.

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were prohibited. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states to be politically imperative that the number of free states not exceed the number of slave states, so new states were admitted in slave–free pairs. There were, nonetheless, some slaves in most free states up to the 1840 census, and the Fugitive Slave Clause of the U.S. Constitution, as implemented by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, provided that a slave did not become free by entering a free state and must be returned to their owner. Enforcement of these laws became one of the controversies which arose between slave and free states.

Abraham Lincoln's position on slavery in the United States is one of the most discussed aspects of his life. Lincoln frequently expressed his moral opposition to slavery in public and private. "I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong," he stated. "I can not remember when I did not so think, and feel." However, the question of what to do about it and how to end it, given that it was so firmly embedded in the nation's constitutional framework and in the economy of much of the country, even though concentrated in only the Southern United States, was complex and politically challenging. In addition, there was the unanswered question, which Lincoln had to deal with, of what would become of the four million slaves if liberated: how they would earn a living in a society that had almost always rejected them or looked down on their very presence.

Lyman Trumbull was an American lawyer, judge, and politician who represented the state of Illinois in the United States Senate from 1855 to 1873. Trumbull was a leading abolitionist attorney and key political ally to Abraham Lincoln and authored several landmark pieces of reform as chair of the Judiciary Committee during the American Civil War and Reconstruction era, including the Confiscation Acts, which created the legal basis for the Emancipation Proclamation; the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which abolished chattel slavery; and the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which led to the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

The 37th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C., from March 4, 1861, to March 4, 1863, during the first two years of Abraham Lincoln's presidency. The apportionment of seats in the House of Representatives was based on the 1850 United States census.

John Woodland Crisfield was a U.S. Representative from Maryland, representing the sixth district from 1847 to 1849 and the first district from 1861 to 1863. The city of Crisfield, Maryland, is named after him. Crisfield was a strong supporter of the Union during American Civil War, opposing moves towards Maryland's secession. However, Crisfield also supported the institution of slavery and worked to prevent its abolition in Maryland.

The Militia Act of 1862 was an Act of the 37th United States Congress, during the American Civil War, that authorized a militia draft within a state when the state could not meet its quota with volunteers. The Act, for the first time, also allowed African-Americans to serve in the militias as soldiers and war laborers. Previous to it, since the Militia Acts of 1792, only white male citizens were permitted to participate in the militias.

The ten percent plan, formally the Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction, was a United States presidential proclamation issued on December 8, 1863, by United States President Abraham Lincoln, during the American Civil War. By this point in the war, the Union Army had pushed the Confederate Army out of several regions of the South, and some Confederate states were ready to have their governments rebuilt. Lincoln's plan established a process through which this postwar reconstruction could come about.

Contraband was a term commonly used in the US military during the American Civil War to describe a new status for certain people who escaped slavery or those who affiliated with Union forces. In August 1861, the Union Army and the US Congress determined that the US would no longer return people who escaped slavery who went to Union lines, but they would be classified as "contraband of war," or captured enemy property. They used many as laborers to support Union efforts and soon began to pay wages.

The Confiscation Act of 1862, or Second Confiscation Act, was a law passed by the United States Congress during the American Civil War. This statute was followed by the Emancipation Proclamation, which President Abraham Lincoln issued "in his joint capacity as President and Commander-in-Chief".

The Confiscation Act of 1861 was an act of Congress during the early months of the American Civil War permitting military confiscation and subsequent court proceedings for any property being used to support the Confederate independence effort, including slaves.

The presidency of Abraham Lincoln began March 4, 1861, when Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as the 16th president of the United States, and ended upon his death on April 15, 1865, 42 days into his second term. Lincoln was the first member of the recently established Republican Party elected to the presidency. Lincoln successfully presided over the Union victory in the American Civil War, which dominated his presidency and resulted in the end of slavery. He was succeeded by Vice President Andrew Johnson.

Slavery played the central role during the American Civil War. The primary catalyst for secession was slavery, especially Southern political leaders' resistance to attempts by Northern antislavery political forces to block the expansion of slavery into the western territories. Slave life went through great changes, as the Southern United States saw Union Armies take control of broad areas of land. During and before the war, enslaved people played an active role in their own emancipation, and thousands of enslaved people escaped from bondage during the war.

An Act for the Release of certain Persons held to Service or Labor in the District of Columbia, 37th Cong., Sess. 2, ch. 54, 12 Stat. 376, known colloquially as the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act or simply Compensated Emancipation Act, was a law that ended slavery in the District of Columbia, while providing slave owners who remained loyal to the United States in the then-ongoing Civil War to petition for compensation. Although not written by him, the act was signed by U.S. President Abraham Lincoln on April 16, 1862. April 16 is now celebrated in the city as Emancipation Day.

From the late 18th to the mid-19th century, various states of the United States allowed the enslavement of human beings, most of whom had been transported from Africa during the Atlantic slave trade or were their descendants. The institution of chattel slavery was established in North America in the 16th century under Spanish colonization, British colonization, French colonization, and Dutch colonization.

First and Second Confiscation Acts (1861, 1862) Major Acts of Congress | 2004 | Hamilton, Daniel W http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-3407400130.html