Deep-sea fish are fish that live in the darkness below the sunlit surface waters, that is below the epipelagic or photic zone of the sea. The lanternfish is, by far, the most common deep-sea fish. Other deep sea fishes include the flashlight fish, cookiecutter shark, bristlemouths, anglerfish, viperfish, and some species of eelpout.

Stomiiformes is an order of deep-sea ray-finned fishes of very diverse morphology. It includes, for example, dragonfishes, lightfishes, loosejaws, marine hatchetfishes and viperfishes. The order contains 4 families with more than 50 genera and at least 410 species. As usual for deep-sea fishes, there are few common names for species of the order, but the Stomiiformes as a whole are often called dragonfishes and allies or simply stomiiforms.

The mesopelagiczone, also known as the middle pelagic or twilight zone, is the part of the pelagic zone that lies between the photic epipelagic and the aphotic bathypelagic zones. It is defined by light, and begins at the depth where only 1% of incident light reaches and ends where there is no light; the depths of this zone are between approximately 200 to 1,000 meters below the ocean surface.

The bathypelagic zone or bathyal zone is the part of the open ocean that extends from a depth of 1,000 to 4,000 m below the ocean surface. It lies between the mesopelagic above and the abyssopelagic below. The bathypelagic is also known as the midnight zone because of the lack of sunlight; this feature does not allow for photosynthesis-driven primary production, preventing growth of phytoplankton or aquatic plants. Although larger by volume than the photic zone, human knowledge of the bathypelagic zone remains limited by ability to explore the deep ocean.

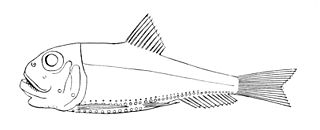

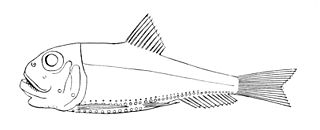

The Gonostomatidae are a family of mesopelagic marine fish, commonly named bristlemouths, lightfishes, or anglemouths. It is a relatively small family, containing only eight known genera and 32 species. However, bristlemouths make up for their lack of diversity with relative abundance, numbering in the hundreds of trillions to quadrillions. The genus Cyclothone is thought to be one of the most abundant vertebrate genera in the world.

Lanternfish are small mesopelagic fish of the large family Myctophidae. One of two families in the order Myctophiformes, the Myctophidae are represented by 246 species in 33 genera, and are found in oceans worldwide. Lanternfishes are aptly named after their conspicuous use of bioluminescence. Their sister family, the Neoscopelidae, are much fewer in number but superficially very similar; at least one neoscopelid shares the common name "lanternfish": the large-scaled lantern fish, Neoscopelus macrolepidotus.

Telescopefish are small, deep-sea aulopiform fish comprising the small family Giganturidae. The two known species are within the genus Gigantura. Though rarely captured, they are found in cold, deep tropical to subtropical waters worldwide.

Pelagic fish live in the pelagic zone of ocean or lake waters—being neither close to the bottom nor near the shore—in contrast with demersal fish that live on or near the bottom, and reef fish that are associated with coral reefs.

A viperfish is any species of marine fish in the genus Chauliodus. Viperfishes are mostly found in the mesopelagic zone and are characterized by long, needle-like teeth and hinged lower jaws. A typical viperfish grows to lengths of 30 cm (12 in). Viperfishes undergo diel vertical migration and are found all around the world in tropical and temperate oceans. Viperfishes are capable of bioluminescence and possess photophores along the ventral side of their body, likely used to camouflage them by blending in with the less than 1% of light that reaches to below 200 meters depth.

The deep sea is broadly defined as the ocean depth where light begins to fade, at an approximate depth of 200 metres or the point of transition from continental shelves to continental slopes. Conditions within the deep sea are a combination of low temperatures, darkness and high pressure. The deep sea is considered the least explored Earth biome as the extreme conditions make the environment difficult to access and explore.

The stoplight loosejaws are small, deep-sea dragonfishes of the genus Malacosteus, classified either within the subfamily Malacosteinae of the family Stomiidae, or in the separate family Malacosteidae. They are found worldwide, outside of the Arctic and Subantarctic, in the mesopelagic zone below a depth of 500 meters. This genus once contained three nominal species: M. niger, M. choristodactylus, and M. danae, with the validity of the latter two species being challenged by different authors at various times. In 2007, Kenaley examined over 450 stoplight loosejaw specimens and revised the genus to contain two species, M. niger and the new M. australis.

Lightfishes are small stomiiform fishes in the family Phosichthyidae

The veiled anglemouth, Cyclothone microdon, is a bristlemouth of the family Gonostomatidae, abundant in all the world's oceans at depths of 300 – 2,500 meters. Its length is 10–15 cm (4–8 in) though the largest known specimen is 7.6 cm (3 in). It gets its name from its circular mouth, filled with small teeth: the name “cyclothone” means in a circle or around and “microdon” means small teeth. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed the veiled anglemouth is of Least Concern due to its abundance in most oceans and the little effect human impact has on its population growth. Some of the veiled anglemouth's physical features include a brown to black body with a radiating, or expansive, bioluminescent pigment over its head and fins.

A deep-sea community is any community of organisms associated by a shared habitat in the deep sea. Deep sea communities remain largely unexplored, due to the technological and logistical challenges and expense involved in visiting this remote biome. Because of the unique challenges, it was long believed that little life existed in this hostile environment. Since the 19th century however, research has demonstrated that significant biodiversity exists in the deep sea.

The oceanic zone is typically defined as the area of the ocean lying beyond the continental shelf, but operationally is often referred to as beginning where the water depths drop to below 200 metres (660 ft), seaward from the coast into the open ocean with its pelagic zone.

Peter John Herring is an English marine biologist known for his work on the coloration, camouflage and bioluminescence of animals in the deep sea, and for the textbook The Biology of the Deep Ocean.

Neoscopelus macrolepidotus, also known as a large-scaled lantern fish, is a species of small mesopelagic or bathypelagic fish of the family Neoscopelidae, which contains six species total along three genera. The family Neoscopelidae is one of the two families of the order Myctophiformes. Neoscopelidae can be classified by the presence of an adipose fin. The presence of photophores, or light-producing organs, further classify the species into the genus Neoscopelus. N. macrolepidotus tends to be mesopelagic until the individuals become large adults, which is when they settle down to the bathypelagic zone.

Cyclothone alba, commonly known as the bristlemouth, is a species of ray-finned fish in the genus Cyclothone. It is found across the world, in the Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic Oceans.

Cyclothone signata, the showy bristlemouth, is a species of ray-finned fish in the genus Cyclothone.

A micronekton is a group of organisms of 2 to 20 cm in size which are able to swim independently of ocean currents. The word 'nekton' is derived from the Greek νήκτον, translit. nekton, meaning "to swim", and was coined by Ernst Haeckel in 1890.