Rhizopogon is a genus of ectomycorrhizal basidiomycetes in the family Rhizopogonaceae. Species form hypogeous sporocarps commonly referred to as "false truffles". The general morphological characters of Rhizopogon sporocarps are a simplex or duplex peridium surrounding a loculate gleba that lacks a columnella. Basidiospores are produced upon basidia that are borne within the fungal hymenium that coats the interior surface of gleba locules. The peridium is often adorned with thick mycelial cords, also known as rhizomorphs, that attach the sporocarp to the surrounding substrate. The scientific name Rhizopogon is Greek for 'root' (Rhiz-) 'beard' (-pogon) and this name was given in reference to the rhizomorphs found on sporocarps of many species.

Hebeloma is a genus of fungi in the family Hymenogastraceae. Found worldwide, it contains the poison pie or fairy cakes (Hebeloma crustuliniforme) and the ghoul fungus (H. aminophilum), from Western Australia, which grows on rotting animal remains.

The sporocarp of fungi is a multicellular structure on which spore-producing structures, such as basidia or asci, are borne. The fruitbody is part of the sexual phase of a fungal life cycle, while the rest of the life cycle is characterized by vegetative mycelial growth and asexual spore production.

Ophiocordyceps unilateralis, commonly known as zombie-ant fungus, is an insect-pathogenic fungus, discovered by the British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace in 1859. Zombie ants, infected by the Ophiocordyceps unilateralis fungus, are predominantly found in tropical rainforests.

Fungivory or mycophagy is the process of organisms consuming fungi. Many different organisms have been recorded to gain their energy from consuming fungi, including birds, mammals, insects, plants, amoebas, gastropods, nematodes, bacteria and other fungi. Some of these, which only eat fungi, are called fungivores whereas others eat fungi as only part of their diet, being omnivores.

Hydnellum caeruleum, commonly known as the blue-gray hydnellum, blue-green hydnellum, blue spine, blue tooth, or bluish tooth, is an inedible fungus found in North America, Europe, and temperate areas of Asia.

Hebeloma aminophilum, commonly known as the ghoul fungus, is a species of mushroom in the family Hymenogastraceae. Found in Western Australia, it gets its common name from the propensity of the fruiting bodies to spring out of decomposing animal remains.

Hebeloma mesophaeum, commonly known as the veiled hebeloma is a species of mushroom in the family Hymenogastraceae. Like all species of its genus, it might be poisonous and result in severe gastrointestinal upset; nevertheless, in Mexico this species is eaten and widely marketed.

Aureoboletus mirabilis, commonly known as the admirable bolete, the bragger's bolete, and the velvet top, is an edible species of fungus in the Boletaceae mushroom family. The fruit body has several characteristics with which it may be identified: a dark reddish-brown cap; yellow to greenish-yellow pores on the undersurface of the cap; and a reddish-brown stem with long narrow reticulations. Aureoboletus mirabilis is found in coniferous forests along the Pacific Coast of North America, and in Asia. Unusual for boletes, A. mirabilis sometimes appears to fruit on the wood or woody debris of Hemlock trees, suggesting a saprobic lifestyle. Despite the occasional appearances to the contrary, Aureoboletus mirabilis is mycorrhizal, and forms a close association with the tree's roots.

Squamanita is a genus of parasitic fungi in the family Squamanitaceae. Basidiocarps superficially resemble normal agarics but emerge from parasitized fruit bodies of deformed host agarics.

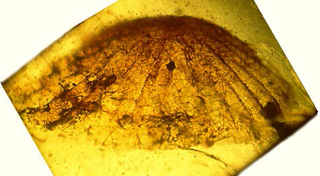

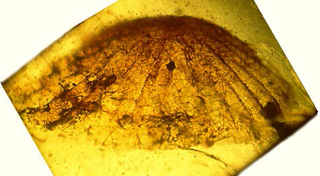

Palaeoagaracites is an extinct monotypic genus of gilled fungus in the order Agaricales. It contains the single species Palaeoagaracites antiquus.

Squamanita schreieri is a species of fungus in the order Agaricales and the type species of the genus Squamanita. It is parasitic on basidiocarps (fruit bodies] of the ectomycorrhizal fungi Amanita solitaria and A. strobiliformis, replacing their caps with its own. The species was first described scientifically by Swiss mycologist Emil J. Imbach in 1946. It is only known from a few sites in central mainland Europe and threats to its habitat have resulted in the species being assessed as globally "endangered" on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

Mycetophagites is an extinct fungal genus of mycoparasitic in the order Hypocreales. A monotypic genus, it contains the single species Mycetophagites atrebora.

Entropezites is an extinct monotypic genus of hypermycoparasitic fungus in the order Hypocreales. At present it contains the single species Entropezites patricii.

Dissoderma paradoxum, which has the recommended English name of powdercap strangler in the UK, is a species of fungus in the family Squamanitaceae. It is a parasitic fungus that grows on the fruit bodies of another fungus, Cystoderma amianthinum. It takes over the host and replaces the cap and gills with its own but retains the original stipe, creating in effect a hybrid between the two. The species was first described as Cystoderma paradoxum by American mycologists Alexander H. Smith and Rolf Singer in 1948, based on specimens collected in Mount Hood National Forest in Oregon. Cornelis Bas transferred the species to the genus Squamanita in 1965. Recent molecular research, based on cladistic analysis of DNA sequences, has however shown that the species does not belong in Squamanita sensu stricto but in the related genus Dissoderma. The species occurs in both North America and Europe.

Amanita augusta, commonly known as the western yellow-veil or western yellow-veiled amanita, is a small tannish-brown mushroom with cap colors bright yellow to dark brown and various combinations of the two colors. The mushroom is often recognizable by the fragmented yellow remnants of the universal veil. This mushroom grows year-round in the Pacific Northwest but fruiting tends to occur in late fall to mid-winter. The fungus grows in an ectomycorrhizal relationship with hardwoods and conifers often in mixed woodlands.

Squamanita contortipes is a small mushroom species in the family Squamanitaceae, formerly in the Tricholomataceae. It was originally described in 1957 by American mycologist Alexander H. Smith and Daniel Elliot Stuntz as a member of Cystoderma. Paul Heinemann and David Thoen transferred it to the genus Squamanita in 1973. Discovery of an unusual fruiting of this species where three fruitbodies grew on one, still fertile host pileus which was a species of Galerina proved that Squamanita was a mycoparasitic genus. Photos of this fruiting were published in 1994 and immediately republished and highlighted in 1995 in Nature magazine where the original discovery article was featured. The species proved to be the Rosetta Stone for deciphering the parasite from the host in graft-like fruitings. Normally, S. contortipes only forms one fruitbody on each parasitized host and the host normally fails to remain fertile and does not form its own pileus.

Leucocoprinus gongylophorus is a fungus in the family Agaricaceae which is cultivated by certain leafcutter ants. Like other species of fungi cultivated by ants, L. gongylophorus produces gongylidia, nutrient-rich hyphal swellings upon which the ants feed. Production of mushrooms occurs only once ants abandon the nest. L. gongylophorus is farmed by leaf cutter ant species belonging to the genera Atta and Acromyrmex, amongst others.

Dissoderma is a genus of parasitic fungi in the family Squamanitaceae. Basidiocarps superficially resemble normal agarics but emerge from parasitized fruit bodies of deformed host agarics.

Biatoropsis usnearum is a species of parasitic fungus that grows exclusively on lichen species of the genus Usnea, particularly U. subfloridana, U. barbata, and U. florida. First described in 1934 by Veli Räsänen, it has become a significant model organism in fungal evolution studies due to its specialised host relationships. The fungus belongs to the order Tremellales, though its precise family classification remains uncertain. It forms distinctive swellings or galls on its host lichens, ranging in colour from pale pink to dark reddish-brown, and notably suppresses the production of host defensive compounds like usnic acid. While initially misclassified due to its unusual characteristics, modern microscopic and genetic studies have revealed it to be part of a species complex, with at least three additional species now recognised. Found across Europe and North America, B. usnearum preferentially infects young, growing parts of its host lichens, particularly branch tips and small branches. The species has become particularly important in understanding how parasitic fungi adapt to new hosts, as it demonstrates evolution through switching between different host species rather than evolving alongside a single host species over time.