Related Research Articles

The economy of Georgia is an emerging free market economy. Its gross domestic product fell sharply following the dissolution of the Soviet Union but recovered in the mid-2000s, growing in double digits thanks to the economic and democratic reforms brought by the peaceful Rose Revolution. Georgia continued its economic progress since "moving from a near-failed state in 2003 to a relatively well-functioning market economy in 2014". In 2007, the World Bank named Georgia the World's number one economic reformer.

The economy of Laos is a lower-middle income developing economy. Being a socialist state, the Lao economic model resembles the Chinese socialist market and/or Vietnamese socialist-oriented market economies by combining high degrees of state ownership with openness to foreign direct investment and private ownership in a predominantly market-based framework.

The economy of Myanmar is the seventh largest in Southeast Asia. After the return of civilian rule in 2011, the new government launched large-scale reforms, focused initially on the political system to restore peace and achieve national unity and moving quickly to an economic and social reform program. Current economic statistics were a huge decline from the economic statistics of Myanmar in the fiscal year of 2020, in which Myanmar’s nominal GDP was $81.26 billion and its purchasing power adjusted GDP was $279.14 billion. Myanmar has faced an economic crisis since the 2021 coup d'état. According to International Monetary Fund (IMF) Myanmar GDP per capita in 2024 is estimated to reach $1.179

The economy of Vietnam is a developing mixed socialist-oriented market economy. It is the 33rd-largest economy in the world by nominal gross domestic product (GDP) and the 26th-largest economy in the world by purchasing power parity (PPP). It is a lower-middle income country with a low cost of living. Vietnam is a member of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and the World Trade Organization.

An agricultural subsidy is a government incentive paid to agribusinesses, agricultural organizations and farms to supplement their income, manage the supply of agricultural commodities, and influence the cost and supply of such commodities.

Nanyang is the Chinese term for the warmer and fertile geographical region along the southern coastal regions of China and beyond, otherwise known as the 'South Sea' or Southeast Asia. The term came into common usage in self-reference to the large ethnic Chinese migrant population in Southeast Asia, and is contrasted with Xiyang, which refers to the Western world, Dongyang, which refers to Japan. The Chinese press regularly uses the term to refer to the region stretching from Yunnan Province to Singapore and from Myanmar (Burma) to Vietnam ; in addition, the term also refers to Brunei, East Malaysia, East Timor, Indonesia and the Philippines in the region it encompasses.

The Licence Raj or Permit Raj is a pejorative for the system of strict government control and regulation of the Indian economy that was in place from the 1950s to the early 1990s. Under this system, businesses in India were required to obtain licences from the government in order to operate, and these licences were often difficult to obtain.

Agriculture in the Empire of Japan was an important component of the pre-war Japanese economy. Although Japan had only 16% of its land area under cultivation before the Pacific War, over 45% of households made a living from farming. Japanese cultivated land was mostly dedicated to rice, which accounted for 15% of world rice production in 1937.

Đổi Mới is the name given to the economic reforms initiated in Vietnam in 1986 with the goal of creating a "socialist-oriented market economy". The term đổi mới itself is a general term with wide use in the Vietnamese language meaning "innovate" or "renovate". However, the Đổi Mới Policy refers specifically to these reforms that sought to transition Vietnam from a command economy to a socialist-oriented market economy.

Economic liberalization, or economic liberalisation, is the lessening of government regulations and restrictions in an economy in exchange for greater participation by private entities. In politics, the doctrine is associated with classical liberalism and neoliberalism. Liberalization in short is "the removal of controls" to encourage economic development.

Thura Shwe Mann is a Burmese politician who was Speaker of the Pyithu Hluttaw, the lower house of parliament from 31 January 2011 to 29 January 2016. He is a former army general and, whilst being a protégé of senior general Than Shwe, was considered the third most powerful man in the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), which ruled Myanmar until 2011.

Since its creation in 1995, the World Trade Organization (WTO) has worked to maintain and develop international trade. As one of the largest international economic organizations, it has strong influence and control over trading rules and agreements, and thus has the ability to affect a country's economy immensely. The WTO policies aim to balance tariffs and other forms of economic protection with a trade liberalization policy, and to "ensure that trade flows as smoothly, predictably and freely as possible". Indeed, the WTO claims that its actions "cut living costs and raise standards, stimulate economic growth and development, help countries develop, [and] give the weak a stronger voice." Statistically speaking, global trade has consistently grown between one and six percent per annum over the past decade, and US$38.8 billion were allocated to Aid for Trade in 2016.

The Ministry of Commerce (MOC) is the Burmese government agency plays a vital role in the transformation process of the implementation of a market-oriented economic system. Its headquarters is located at Building 3 and 52, Nay Pyi Taw, in Myanmar.

Retailing in India is one of the pillars of its economy and accounts for about 10 percent of its GDP. The Indian retail market is estimated to be worth $1.3 trillion as of 2022. India is one of the fastest growing retail markets in the world, with 1.4 billion people.

The economic liberalisation in India refers to the series of policy changes aimed at opening up the country's economy to the world, with the objective of making it more market-oriented and consumption-driven. The goal was to expand the role of private and foreign investment, which was seen as a means of achieving economic growth and development. Although some attempts at liberalisation were made in 1966 and the early 1980s, a more thorough liberalisation was initiated in 1991.

Globalization is a process that encompasses the causes, courses, and consequences of transnational and transcultural integration of human and non-human activities. India had the distinction of being the world's largest economy till the end of the Mughal era, as it accounted for about 32.9% share of world GDP and about 17% of the world population. The goods produced in India had long been exported to far off destinations across the world; the concept of globalization is hardly new to India.

The Chinese economic reform or Chinese economic miracle, also known domestically as reform and opening-up, refers to a variety of economic reforms termed "socialism with Chinese characteristics" and "socialist market economy" in the People's Republic of China (PRC) that began in the late 20th century, after Mao Zedong's death in 1976. Guided by Deng Xiaoping, who is often credited as the "General Architect", the reforms were launched by reformists within the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) on December 18, 1978, during the Boluan Fanzheng period.

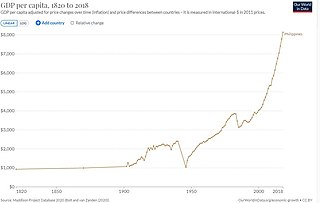

The economic history of the Philippines is shaped by its colonial past, evolving governance, and integration into the global economy.

Myanma Economic Holdings Public Company Limited is one of two major conglomerates run by the Burmese military, the other being the Myanmar Economic Corporation (MEC). MEHL business interests include banking, construction, mining, agriculture, tobacco and food.

Zaw Win Shein is a Burmese businessperson best known for founding Ayeyar Hinthar Holdings. He was born and raised in the Ayeyarwady Delta Region; Hinthada Township, which is Myanmar's main rice-producing region. At the age of 16, after his matriculation, Zaw Win Shein worked as an apprentice in his parents' agricultural products and rice export business. His father is U Thann Sein. Zaw Win Shein embarked on his business journey at 19, borrowing a few hundred thousand dollars from his parents to establish Seven Aluminium Company in 2006, addressing the scarcity of construction materials and quality aluminum fabrication in Myanmar. In 2007, he initiated Ayeyar Hinthar Trading Co., exporting high-quality rice and agricultural products, and capitalizing on government policy changes.

References

- ↑ Springer, John. "Reflecting On Myanmar's (Burma's) Future". Forbes.com. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ↑ Fenichel, Allen; Khan, Azfar (1981). "The Burmese Way to 'Socialism'". World Development. 9 (9110): 813–824. doi:10.1016/0305-750x(81)90043-7.

- ↑ Cook, Paul; Minogue, Martin (1993). "Economic Reform and Political Change in Myanmar (Burma)". World Development. 21 (7): 1152. doi:10.1016/0305-750x(93)90005-t.

- ↑ Rigg, Jonathan (1997). Southeast Asia : the human landscape of modernization and development (Reprint. ed.). London: Routledge. p. 15. ISBN 0415139201.

- ↑ Kubo, Koji (2013). "Myanmar's two decades of partial transition to a market economy: a negative legacy for the new government". Post-Communist Economies. 25 (3): 358. doi:10.1080/14631377.2013.813141. S2CID 154466296.

- ↑ Rigg, Jonathan (1997). Southeast Asia : the human landscape of modernization and development (Reprint. ed.). London: Routledge. p. 15. ISBN 0415139201.

- ↑ UNDP. "About Myanmar". mm.undp.org. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ↑ Okamoto,Ikuko. "Chapter 7: Transforming Myanmar’s rice marketing" in Skidmore, Monique; (eds.), Trevor Wilson (2007). Myanmar : the state, community and the environment. Canberra: Asia Pacific Press. p. 152. ISBN 9780731538119.

{{cite book}}:|last2=has generic name (help) - ↑ Rigg, Jonathan (1997). Southeast Asia : the human landscape of modernization and development (Reprint. ed.). London: Routledge. p. 15. ISBN 0415139201.

- ↑ Bissinger, Jared (2012). "Foreign Investment in Myanmar: A Resource Boom but a Development Bust?". Contemporary Southeast Asia. 34 (1): 23–52. doi:10.1355/cs34-1b.

- ↑ Thawnghmung, Ardeth Maung (2004). Behind the teak curtain : authoritarianism, agricultural policies and political legitimacy in rural Burma/Myanmar ([New ed.]. ed.). London [u.a.]: Kegan Paul. p. 134. ISBN 071030935X.

- ↑ Okamoto,Ikuko. "Chapter 7: Transforming Myanmar’s rice marketing" in Skidmore, Monique; (eds.), Trevor Wilson (2007). Myanmar : the state, community and the environment. Canberra: Asia Pacific Press. p. 154. ISBN 9780731538119.

{{cite book}}:|last2=has generic name (help) - ↑ Thawnghmung, Ardeth Maung (2004). Behind the teak curtain : authoritarianism, agricultural policies and political legitimacy in rural Burma/Myanmar ([New ed.]. ed.). London [u.a.]: Kegan Paul. p. 134. ISBN 071030935X.

- ↑ Myint, Tun "Chapter 9: Environmental governance" in Skidmore, Monique; (eds.), Trevor Wilson (2007). Myanmar : the state, community and the environment. Canberra: Asia Pacific Press. p. 200. ISBN 9780731538119.

{{cite book}}:|last2=has generic name (help) - ↑ "Sold Out" (PDF). shwe.org/. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ↑ Hudson-Rodd, Nancy; Htay, Sein (2008). Arbitrary confiscation of farmers' land by the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) military regime in Burma (1st pub. ed.). Rockville, MD: The Burma Fund. p. 87. ISBN 978-974-8349-36-7.

- ↑ McCarthy, Stephen (2000). "Ten Years of Chaos in Burma: Foreign Investment and Economic Liberalization under the SLORC-SPDC, 1988 to 1998". Pacific Affairs. 73 (2): 235. doi:10.2307/2672179. JSTOR 2672179.

- ↑ McCarthy, Stephen (2000). "Ten Years of Chaos in Burma: Foreign Investment and Economic Liberalization under the SLORC-SPDC, 1988 to 1998". Pacific Affairs. 73 (2): 235. doi:10.2307/2672179. JSTOR 2672179.

- ↑ Turnell,Sean. "Chapter 6: Myanmar’s economy in 2006" in Skidmore, Monique; (eds.), Trevor Wilson (2007). Myanmar : the state, community and the environment. Canberra: Asia Pacific Press. p. 122. ISBN 9780731538119.

{{cite book}}:|last2=has generic name (help) - ↑ Shobert, Benjamin. "Myanmar Enters A Critical Transition". Forbes.com. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ↑ Haggblade, Steven; et al. (2014). "Strategic Choices Shaping Agriculture Performance and Food Security on Myanmar". Journal of International Affairs. 67 (2): 59.

- ↑ Kattelus, Mirja; Rahaman, Muhammad Mizanur; Varis, Olli (2014). "Myanmar under reform: Emerging pressures on water, energy and food security". Natural Resources Forum. 38 (2): 93. doi:10.1111/1477-8947.12032.

- ↑ Maung Kyi, Khin; et al. (2000). Economic development of Burma : a vision and a strategy. Stockholm, Sweden: Olof Palme Internat. Center. p. 131. ISBN 918-883616-9.

- ↑ Maung Kyi, Khin; et al. (2000). Economic development of Burma : a vision and a strategy. Stockholm, Sweden: Olof Palme Internat. Center. p. 134. ISBN 918-883616-9.

- ↑ Thawnghmung, Ardeth Maung (2004). Behind the teak curtain : authoritarianism, agricultural policies and political legitimacy in rural Burma/Myanmar ([New ed.]. ed.). London [u.a.]: Kegan Paul. p. 149. ISBN 071030935X.

- ↑ Kattelus, Mirja; Rahaman, Muhammad Mizanur; Varis, Olli (2014). "Myanmar under reform: Emerging pressures on water, energy and food security". Natural Resources Forum. 38 (2): 90. doi:10.1111/1477-8947.12032.

- ↑ Hudson-Rodd, Nancy; Htay, Sein (2008). Arbitrary confiscation of farmers' land by the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) military regime in Burma (1st pub. ed.). Rockville, MD: The Burma Fund. p. 88. ISBN 978-974-8349-36-7.

- ↑ Haggblade, Steven; et al. (2014). "Strategic Choices Shaping Agriculture Performance and Food Security on Myanmar". Journal of International Affairs. 67 (2): 55–56.

- ↑ Haggblade, Steven; et al. (2014). "Strategic Choices Shaping Agriculture Performance and Food Security on Myanmar". Journal of International Affairs. 67 (2): 55.

- ↑ Bland, Ben. "Western investors target Burma". Financial Times. Retrieved 3 October 2014.