Infanticide is the intentional killing of infants or offspring. Infanticide was a widespread practice throughout human history that was mainly used to dispose of unwanted children, its main purpose being the prevention of resources being spent on weak or disabled offspring. Unwanted infants were usually abandoned to die of exposure, but in some societies they were deliberately killed. Infanticide is generally illegal, but in some places the practice is tolerated, or the prohibition is not strictly enforced.

Sex-selective abortion is the practice of terminating a pregnancy based upon the predicted sex of the infant. The selective abortion of female fetuses is most common where male children are valued over female children, especially in parts of East Asia and South Asia, as well as in the Caucasus, Western Balkans, and to a lesser extent North America. Based on the third National Family and Health Survey, results showed that if both partners, mother and father, or just the father, preferred male children, sex-selective abortion was more common. In cases where only the mother prefers sons, this is likely to result in sex-selective neglect in which the child is not likely to survive past infancy.

Female infanticide is the deliberate killing of newborn female children. Female infanticide is prevalent in several nations around the world. It has been argued that the low status in which women are viewed in patriarchal societies creates a bias against females. The modern practice of gender-selective abortion is also used to regulate gender ratios.

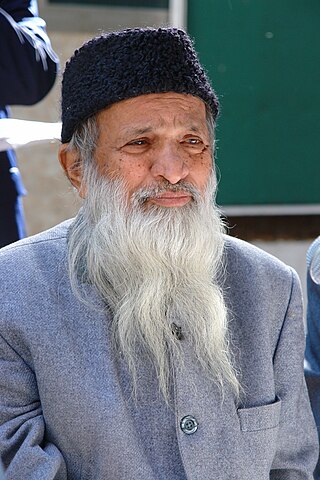

Abdul Sattar EdhiNI LPP was a Pakistani humanitarian, philanthropist and ascetic who founded the Edhi Foundation, which runs the world's largest ambulance network, along with homeless shelters, animal shelters, rehabilitation centres, and orphanages across Pakistan.

Bilquis Bano Edhi was a Pakistani nurse who helped save the lives of over 16,000 children. During her career as a nurse and marriage to Abdul Sattar Edhi, she was one of the most active philanthropists in Pakistan. She was the co-chair of the Edhi Foundation, a charity organization that provided many services in Pakistan including a hospital and emergency service in Karachi. For her contributions, she was awarded the 1986 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Public Service and the Mother Teresa Memorial International Award for Social Justice in 2015. She was also a recipient of Hilal-i-Imtiaz, Pakistan's second highest civilian honour. For her service to the country, she was also referred to as The Mother of Pakistan.

Sex selection is the attempt to control the sex of the offspring to achieve a desired sex. It can be accomplished in several ways, both pre- and post-implantation of an embryo, as well as at childbirth. It has been marketed under the title family balancing.

The status of women in India has been subject to many changes over the time of recorded India's history. Their position in society underwent significant changes during India's ancient period, particularly in the Indo-Aryan speaking regions, and their subordination continued to be reified well into India's early modern period.

Women in Pakistan make up 48.76% of the population according to the 2017 census of Pakistan. Women in Pakistan have played an important role in Pakistani history and have had the right to vote since 1956. In Pakistan, women have held high office including Prime Minister, Speaker of the National Assembly, Leader of the Opposition, as well as federal ministers, judges, and serving commissioned posts in the armed forces, with Lieutenant General Nigar Johar attaining the highest military post for a woman. Benazir Bhutto was sworn in as the first woman Prime Minister of Pakistan on 2 December 1988.

Gendercide is the systematic killing of members of a specific gender. The term is related to the general concepts of assault and murder against victims due to their gender, with violence against men and women being problems dealt with by human rights efforts. Gendercide shares similarities with the term 'genocide' in inflicting mass murders; however, gendercide targets solely one gender, being men or women. Politico-military frameworks have historically inflicted militant-governed divisions between femicide and androcide; gender-selective policies increase violence on gendered populations due to their socioeconomic significance. Certain cultural and religious sentiments have also contributed to multiple instances of gendercide across the globe.

Gender inequality in India refers to health, education, economic and political inequalities between men and women in India. Various international gender inequality indices rank India differently on each of these factors, as well as on a composite basis, and these indices are controversial.

In the context of human demographics, the term "missing women" indicates a shortfall in the number of women relative to the expected number of women in a region or country. It is most often measured through male-to-female sex ratios, and is theorized to be caused by sex-selective abortions, female infanticide, and inadequate healthcare and nutrition for female children. It is argued that technologies that enable prenatal sex selection, which have been commercially available since the 1970s, are a large impetus for missing female children.

Female foeticide in India is the abortion of a female foetus outside of legal methods. A research by Pew Research Center based on Union government data indicates foeticide of at least 9 million females in the years 2000–2019. The research found that 86.7% of these foeticides were by Hindus, followed by Sikhs with 4.9%, and Muslims with 6.6%. The research also indicated an overall decline in preference for sons or daughter in the time period.

China has a history of female infanticide which spans 2,000 years. When Christian missionaries arrived in China in the late sixteenth century, they witnessed newborns being thrown into rivers or onto rubbish piles. In the seventeenth century Matteo Ricci documented that the practice occurred in several of China's provinces and said that the primary reason for the practice was poverty. The practice continued into the 19th century and declined precipitously after the proclamation of the People's Republic of China, but reemerged as an issue after the PRC government introduced the one-child policy in the early 1980s. The 2020 census showed a male-to-female ratio of 105.07 to 100 for mainland China, a record low since the People's Republic of China (PRC) began conducting censuses. Every year in the PRC and India alone, there are close to two million instances of some form of female infanticide.

Female infanticide in India has a history spanning centuries. Poverty, the dowry system, births to unmarried women, deformed infants, famine, lack of support services, and maternal illnesses such as postpartum depression are among the causes that have been proposed to explain the phenomenon of female infanticide in India.

For years, the census data in China has recorded a significant imbalance in the sex ratio toward the male population, meaning there are fewer women than men. This phenomenon is sometimes referred to as the missing women or missing girls of China. In 2021, China's official census report showed a sex ratio of 112 male to 100 female births, compared to a global average of 105 or 106 male to 100 female births. This is down from a high of 118 male to 100 female births from 2002 to 2008. The sex imbalance in some rural areas is higher, at 130 boys to 100 girls.

Violence against women in India refers to physical or sexual violence committed against a woman, typically by a man.

Sex-selective abortion is the act of aborting a child due to its predicted sex. This practice gained popularity in the mid-1980s to early 1990s in South Korea, where selective female abortions were commonplace as male children were preferred. As a result, South Koreans aborted a much higher number of female fetuses than male ones in the 1980s and early 1990s. Historically, much of Korea's values and traditions were based on Confucianism, which dictates a patriarchal system, thus motivating the preference for sons over daughters. Additionally, even though the abortion ban existed, the combination of son preference and availability of sex-selective technology led to an increasing number of sex-selective abortions and boys born. As a result, South Korea experienced drastically high sex ratios around mid-1980s to early 1990s. However, in recent years, with the changes in family policies and modernization, attitudes towards son preference have changed, normalizing the sex ratio and lowering the number of sex-selective abortions. Additionally, during the entire 20th century South Korean women benefitted greatly from gender inequality declining at one of the fastest rates worldwide. However, there has been no explicit data collected on the number of induced sex selective abortions performed due to the abortion ban and controversy surrounding the topic. Therefore, scholars have been continuously analyzing and generating connections among sex-selection, abortion policies, gender discrimination, and other cultural factors.

The gender gap in Pakistan refers to the differences between men and women in Pakistan in terms of social, political, and economic participation and rights. The gender gap uses the gender ratio of Pakistan to compare the disparities between men and women in different fields, which mainly disadvantage women. According to the Global Gender Gap Index 2022, Pakistan ranks second to last in terms of the Gender Gap, with only 56.4% of its gender gap closed, a 0.8 percentage point increase from 2021. By percentage, men form about 51.46% and women form about 48.54% of the total population of Pakistan. The sex ratio of Pakistan is 106.010, that means there are about 106 men for every 100 women in Pakistan. The gender gap in Pakistan includes comparisons of gender differences in health, educational, legal, economical, and political aspects.

The #MeToo movementin Pakistan is modeled after the international #MeToo movement and began in late 2018 in Pakistani society. It has been used as a springboard to stimulate a more inclusive, organic movement, adapted to local settings, and has aimed to reach all sectors, including the lowest rungs of society.