The Tydings–McDuffie Act, officially the Philippine Independence Act, is a United States federal law that established the process for the Philippines, then an American territory, to become an independent country after a ten-year transition period. Under the act, the 1935 Constitution of the Philippines was written and the Commonwealth of the Philippines was established, with the first directly elected President of the Philippines. It also established limitations on Filipino immigration to the United States.

The Commonwealth of the Philippines was the administrative body that governed the Philippines from 1935 to 1946, aside from a period of exile in the Second World War from 1942 to 1945 when Japan occupied the country. It was established following the Tydings–McDuffie Act to replace the Insular Government, a United States territorial government. The Commonwealth was designed as a transitional administration in preparation for the country's full achievement of independence. Its foreign affairs remained managed by the United States.

The resident commissioner of the Philippines was a non-voting member of the United States House of Representatives sent by the Philippines from 1907 until its internationally recognized independence in 1946. It was similar to current non-voting members of Congress such as the resident commissioner of Puerto Rico and delegates from Washington, D.C., Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands and other territories of the United States.

Manuel Acuña Roxas was the fifth president of the Philippines, who served from 1946 until his death in 1948. He briefly served as the third and last president of the Commonwealth of the Philippines from May 28, 1946, to July 4, 1946, and became the first president of the independent Third Philippine Republic after the United States ceded its sovereignty over the Philippines.

The Hare–Hawes–Cutting Act passed to authors Congress Butler B. Hare, Senator Harry B. Hawes and Senator Bronson M. Cutting. The Hare–Hawes–Cutting Act was the first US law passed setting a process and a date for the Philippines to gain independence from the United States. It was the result of the OsRox Mission led by Sergio Osmeña and Manuel Roxas. The law promised Philippine independence after 10 years, but reserved several military and naval bases for the United States, as well as imposed tariffs and quotas on Philippine imports.

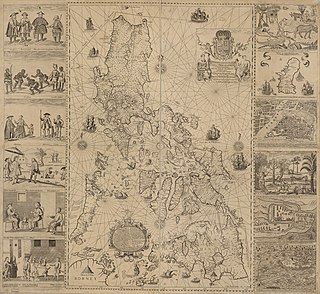

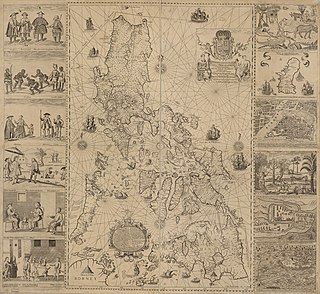

Filipino nationalism refers to the establishment and support of a political identity associated with the modern nation-state of the Philippines, leading to a wide-ranging campaign for political, social, and economic freedom in the Philippines. This gradually emerged from various political and armed movements throughout most of the Spanish East Indies—but which has long been fragmented and inconsistent with contemporary definitions of such nationalism—as a consequence of more than three centuries of Spanish rule. These movements are characterized by the upsurge of anti-colonialist sentiments and ideals which peaked in the late 19th century led mostly by the ilustrado or landed, educated elites, whether peninsulares, insulares, or native (Indio). This served as the backbone of the first nationalist revolution in Asia, the Philippine Revolution of 1896. The modern concept would later be fully actualized upon the inception of a Philippine state with its contemporary borders after being granted independence by the United States by the 1946 Treaty of Manila.

Asian immigration to the United States refers to immigration to the United States from part of the continent of Asia, which includes East Asia, Southeast Asia, and South Asia. Historically, immigrants from other parts of Asia, such as West Asia were once considered "Asian", but are considered immigrants from the Middle East. Asian-origin populations have historically been in the territory that would eventually become the United States since the 16th century. The first major wave of Asian immigration occurred in the late 19th century, primarily in Hawaii and the West Coast. Asian Americans experienced exclusion, and limitations to immigration, by the United States law between 1875 and 1965, and were largely prohibited from naturalization until the 1940s. Since the elimination of Asian exclusion laws and the reform of the immigration system in the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, there has been a large increase in the number of immigrants to the United States from Asia.

Founded in 1895, the Hawaiian Sugar Planters' Association (HSPA) was an unincorporated, voluntary organization of sugarcane plantation owners in the Hawaiian Islands. Its objective was to promote the mutual benefits of its members and the development of the sugar industry in the islands. It conducted scientific studies and gathered accurate records about the sugar industry. The HSPA practiced paternalistic management. Plantation owners introduced welfare programs, sometimes out of concern for the workers, but often designed to suit their economic ends. Threats, coercion, and "divide and rule" tactics were employed, particularly to keep the plantation workers ethnically segregated.

The history of the Philippines from 1898 to 1946 began with the outbreak of the Spanish–American War in April 1898, when the Philippines was still a colony of the Spanish East Indies, and concluded when the United States formally recognized the independence of the Republic of the Philippines on July 4, 1946.

This article covers the history of the Philippines from the recognition of independence in 1946 to the end of the presidency of Diosdado Macapagal that covered much of the Third Republic of the Philippines, which ended on January 17, 1973 with the ratification of the 1973 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines.

The National Assembly of the Philippines refers to the legislature of the Commonwealth of the Philippines from 1935 to 1941, and of the Second Philippine Republic during the Japanese occupation. The National Assembly of the Commonwealth was created under the 1935 Constitution, which served as the Philippines' fundamental law to prepare it for its independence from the United States of America.

The Mutual Defense Treaty between the Republic of the Philippines and the United States of America (MDT) is a treaty that was signed on August 30, 1951, in Washington, DC, between representatives of the Philippines and the United States. The overall accord contains eight articles and dictates for both nations to support each other if an external party attacks the Philippines or the United States.

The Treaty of Manila of 1946, formally the Treaty of General Relations and Protocol, is a treaty of general relations signed on July 4, 1946 in Manila, the capital of the Philippines. It relinquished U.S. sovereignty over the Philippines and recognized the independence of the Republic of the Philippines. The treaty was signed by High Commissioner Paul V. McNutt as representative of the United States and President Manuel Roxas as representative of the Philippines.

The Constitution of the Philippines is the constitution or supreme law of the Republic of the Philippines. Its final draft was completed by the Constitutional Commission on October 12, 1986, and was ratified by a nationwide plebiscite on February 2, 1987.

The Insular Government of the Philippine Islands was an unincorporated territory of the United States that was established in 1901 and was dissolved in 1935 in the Philippines. The Insular Government was preceded by the United States Military Government of the Philippine Islands and was followed by the Commonwealth of the Philippines.

The OsRox Mission (1931) was a campaign for self-government and United States recognition of the independence of the Philippines led by former Senate President Sergio Osmeña and House Speaker Manuel Roxas. The mission secured the Hare–Hawes–Cutting Act, which was rejected by the Philippine Legislature and Manuel Quezon.

Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America, is a Frederick Jackson Turner Award-winning book by historian Mae M. Ngai published by Princeton University Press in 2004.

The Pensionado Act is Act Number 854 of the Philippine Commission, which passed on 26 August 1903. Passed by the United States Congress, it established a scholarship program for Filipinos to attend school in the United States. The program has roots in pacification efforts following the Philippine–American War. It hoped to prepare the Philippines for self-governance and present a positive image of Filipinos to the rest of the United States. Students of this scholarship program were known as pensionados.

The Yakima Valley riots were an expression of anti-Filipino sentiment that took place in the Yakima Valley of Washington (state) from November 8–11 in 1927. This riot took the homes and jobs lives of many Filipinos in the area. Unable to receive help or protection from the white police, Filipinos were easy targets for radicalized and angered whites who saw them as thieves of their women and jobs. Under the cover or darkness, and occasionally during the daytime, mobs of white men would harass, threaten, and beat innocent Filipinos for no other reason than their presence.

The manong generation were the first generation of Filipino immigrants to arrive en masse to the United States. They formed some of the first Little Manila communities in the United States, and they played a pivotal role in the farmworker movement. The term manong comes from the Ilocano word for "elder brother," while manang means "elder sister."