Related Research Articles

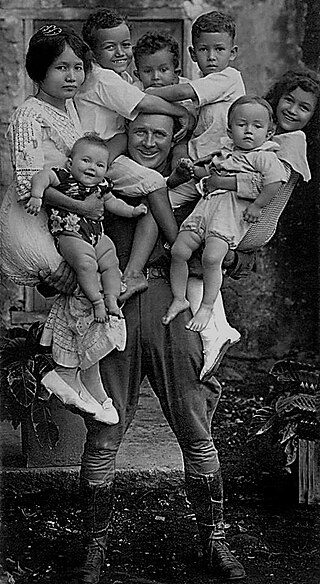

An Amerasian may refer to a person born in East or Southeast Asia to an East Asian or Southeast Asian mother and a U.S. military father. Other terms used include War babies or G.I. babies.

Vietnamese Americans are Americans of Vietnamese ancestry. They constitute a major part of all overseas Vietnamese. As of 2023, over 2.3 million people of Vietnamese descent live in the United States, making them one of the largest Asian American ethnic groups. The majority (60%) are immigrants, while 40% were born in the United States.

The Orderly Departure Program(ODP) was a program to permit immigration of Vietnamese to the United States and to other countries. It was created in 1979 under the auspices of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The objective of the ODP was to provide a mechanism for Vietnamese to leave their homeland safely and in an orderly manner to be resettled abroad. Prior to the ODP, tens of thousands of "boat people" were fleeing Vietnam monthly by boat and turning up on the shores of neighboring countries. Under the ODP, from 1980 until 1997, 623,509 Vietnamese were resettled abroad of whom 458,367 went to the United States.

A K-1 visa is a visa issued to the fiancé or fiancée of a United States citizen to enter the United States. A K-1 visa requires a foreigner to marry his or her U.S. citizen petitioner within 90 days of entry, or depart the United States. Once the couple marries, the foreign citizen can adjust status to become a lawful permanent resident of the United States. Although a K-1 visa is legally classified as a non-immigrant visa, it usually leads to important immigration benefits and is therefore often processed by the Immigrant Visa section of United States embassies and consulates worldwide.

Parole, in the immigration laws of the United States, generally refers to official permission to enter and remain temporarily in the United States, under the supervision of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), without formal admission, and while remaining an applicant for admission.

American settlement in the Philippines began during the Spanish colonial period. The period of American colonization of the Philippines was 48 years long. It began with the cession of the Philippines to the U.S. by Spain in 1898 and lasted until the U.S. recognition of Philippine independence in 1946.

The Naturalization Act of 1790 was a law of the United States Congress that set the first uniform rules for the granting of United States citizenship by naturalization. The law limited naturalization to "free white person(s) ... of good character". This eliminated ambiguity on how to treat newcomers, given that free black people had been allowed citizenship at the state level in many states. In reading the Naturalization Act, the courts also associated whiteness with Christianity and thus excluded Muslim immigrants from citizenship until the decision Ex Parte Mohriez recognized citizenship for a Saudi Muslim man in 1944.

The Vietnamese term bụi đời refers to vagrants in the city or, trẻ bụi đời to street children or juvenile gangs. From 1989, following a song in the musical Miss Saigon, "Bui-Doi" came to popularity in Western lingo, referring to Amerasian children left behind in Vietnam after the Vietnam War.

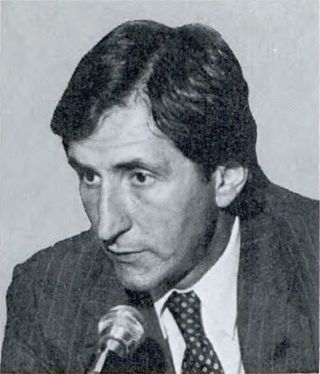

Robert Jan Mrazek is an American author, filmmaker, and former politician. He served as a Democratic member of the United States House of Representatives, representing New York's 3rd congressional district on Long Island for most of the 1980s. Since leaving Congress, Mrazek has authored twelve books, earning the W. Y. Boyd Literary Award for Excellence in Military Fiction from the American Library Association, the Michael Shaara award for Civil War fiction, and Best Book from the Washington Post. He also wrote and co-directed the 2016 feature film The Congressman, which received the Breakout Achievement Award at the AARP's Film Awards in 2017.

The United States recognizes the right of asylum for individuals seeking protections from persecution, as specified by international and federal law. People who seek protection while outside the U.S. are termed refugees, while people who seek protection from inside the U.S. are termed asylum seekers. Those who are granted asylum are termed asylees.

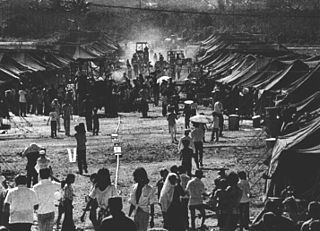

Operation New Life was the care and processing on Guam of Vietnamese refugees evacuated before and after the Fall of Saigon, the closing day of the Vietnam War. More than 111,000 of the evacuated 130,000 Vietnamese refugees were transported to Guam, where they were housed in tent cities for a few weeks while being processed for resettlement. The great majority of the refugees were resettled in the United States. A few thousand were resettled in other countries or chose to return to Vietnam on the vessel Thuong Tin.

The Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act, passed on May 23, 1975, under President Gerald Ford, was a response to the Fall of Saigon and the end of the Vietnam War. Under this act, approximately 130,000 refugees from South Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia were allowed to enter the United States under a special status, and the act allotted special relocation aid and financial assistance.

Vietnamese boat people were refugees who fled Vietnam by boat and ship following the end of the Vietnam War in 1975. This migration and humanitarian crisis was at its highest in the late 1970s and early 1980s, but continued well into the early 1990s. The term is also often used generically to refer to the Vietnamese people who left their country in a mass exodus between 1975 and 1995. This article uses the term "boat people" to apply only to those who fled Vietnam by sea.

Trương Minh Hà, known under the stage name of Thanh Hà, is a Vietnamese American singer.

The Indochina refugee crisis was the large outflow of people from the former French colonies of Indochina, comprising the countries of Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, after communist governments were established in 1975. Over the next 25 years and out of a total Indochinese population in 1975 of 56 million, more than 3 million people would undertake the dangerous journey to become refugees in other countries of Southeast Asia, Hong Kong, or China. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 250,000 Vietnamese refugees had perished at sea by July 1986. More than 2.5 million Indochinese were resettled, mostly in North America, Australia, and Europe. More than 525,000 were repatriated, either voluntarily or involuntarily, mainly from Cambodia.

The Armed Forces Immigration Adjustment Act 1991, also known as the Six and Six Program, was enacted on October 1, 1991. The Act amended the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, also known as the Hart-Celler Act.

Paper sons or paper daughters are Chinese people who were born in China and illegally immigrated to the United States and Canada by purchasing documentation which stated that they were blood relatives to Chinese people who had already received U.S. or Canadian citizenship or residency. Typically it would be relation by being a son or a daughter. Several historical events such as the Chinese Exclusion Act and 1906 San Francisco earthquake caused the illegal documents to be produced.

The Philippines–South Vietnam relations refers to the bilateral relations of the Republic of the Philippines and the now defunct-Republic of Vietnam. The Philippines was an ally to South Vietnam during the Vietnam War providing humanitarian aid.

Federal policy oversees and regulates immigration to the United States and citizenship of the United States. The United States Congress has authority over immigration policy in the United States, and it delegates enforcement to the Department of Homeland Security. Historically, the United States went through a period of loose immigration policy in the early-19th century followed by a period of strict immigration policy in the late-19th and early-20th centuries. Policy areas related to the immigration process include visa policy, asylum policy, and naturalization policy. Policy areas related to illegal immigration include deferral policy and removal policy.

The U.S. Citizenship Act of 2021 was a legislative bill that was proposed by President Joe Biden on his first day in office. It was formally introduced in the House by Representative Linda Sánchez. It died with the ending of the 117th Congress.

References

- ↑ Asian-Nation : Asian American History, Demographics, & Issues :: Vietnamese Amerasians in America

- ↑ Daniels, Roger, and Otis L. Graham. Debating American Immigration, 1882--present. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2001.

- ↑ Johnson, Kay (May 13, 2002). "Children of the Dust". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Archived from the original on May 7, 2007. Retrieved 2015-09-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bankston, Carl L. (2012). "Amerasian Homecoming Act of 1988". Encyclopedia of Diversity in Education. doi:10.4135/9781452218533.n34. ISBN 9781412981521.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "History of U.S. Response to Amerasians." University of California Calisphere. January 1, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Yarborough, Trin. 2005. Surviving twice: Amerasian children of the Vietnam War. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books.

- 1 2 3 4 Hoang Chuong, Chung. "The Amerasians from Vietnam: A California Study." Bilingual Education Office California Department of Education, 1994. https://renincorp.org/other-publications/handbooks/amerasn.pdf.

- 1 2 3 4 "H.R.3171 – Amerasian Homecoming Act." Library of Congress. https://www.congress.gov/bill/100th-congress/house-bill/3171.

- ↑ "Filipinos Fathered by US Soldiers Fight for Justice." The Guardian. December 31, 2012.

- ↑ Valverde, Kieu Linh Caroline. 1992. "From Dust to Gold: The Vietnamese Amerasian Experience" in Racially Mixed People in America, edited by M. P. P. Root. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.