Bauxite is a sedimentary rock with a relatively high aluminium content. It is the world's main source of aluminium and gallium. Bauxite consists mostly of the aluminium minerals gibbsite (Al(OH)3), boehmite (γ-AlO(OH)) and diaspore (α-AlO(OH)), mixed with the two iron oxides goethite (FeO(OH)) and haematite (Fe2O3), the aluminium clay mineral kaolinite (Al2Si2O5(OH)4) and small amounts of anatase (TiO2) and ilmenite (FeTiO3 or FeO.TiO2). Bauxite appears dull in luster and is reddish-brown, white, or tan.

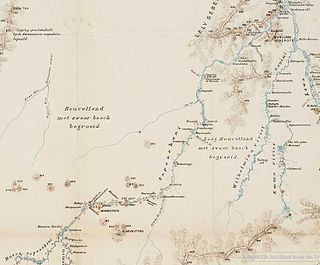

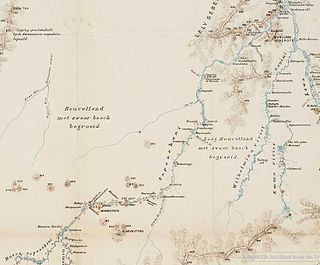

Marowijne is a district of Suriname, located on the north-east coast. Marowijne's capital city is Albina, with other towns including Moengo and Wanhatti. The district borders the Atlantic Ocean to the north, French Guiana to the east, the Surinamese district of Sipaliwini to the south, and the Surinamese districts of Commewijne and Para to the west.

Sipaliwini is the largest district of Suriname, located in the south. Sipaliwini is the only district that does not have a regional capital, as it is directly administered by the national government in Paramaribo.

The Maroni or Marowijne is a river in South America that forms the border between French Guiana and Suriname.

The Tapanahony River is a major river in the south eastern part of Suriname, South America. The river originates in the Southern part of the Eilerts de Haan Mountains, near the border with Brazil. It joins the Marowijne River at a place called Stoelmanseiland. Upstream, there are many villages inhabited by Indian Tiriyó people, while further downstream villages are inhabited by the Amerindian Wayana and Maroon Ndyuka people.

The Coppename is a river in Suriname in the district of Sipaliwini, forming part of the boundary between the districts of Coronie and Saramacca.

Commewijne River is a river in northern Suriname.

The Eilerts de Haan Mountains are a mountain range in Sipaliwini District, Suriname. It is a southern part of Wilhelmina Mountains and is maximum 986 m high. The mountain range is part of the Central Suriname Nature Reserve.

The Tumuk Humak Mountains are a mountain range in South America, stretching about 120 kilometers (75 mi) east–west in the border area between Brazil in the south and Suriname and French Guiana in the north. In the language of the Apalam and Wayana peoples, Tumucumaque means "the mountain rock symbolizing the struggle between the shaman and the spirits". The range is very remote and almost inaccessible.

Angadipuram Laterite is a notified National Geo-heritage Monument in Angadipuram town in Malappuram district in the southern Indian state of Kerala, India. The special significance of Angadipuram to laterites is that it was here that Dr. Francis Buchanan-Hamilton, a professional surgeon, gave the first account of this rock type, in his report of 1807, as "indurated clay", ideally suited for building construction. This formation falls outside the general classification of rocks namely, the igneous, metamorphic, or sedimentary rocks but is an exclusively "sedimentary residual product". It has generally a pitted and porous appearance. The name laterite was first coined in India, by Buchanan and its etymology is traced to the Latin word "letritis" that means bricks. This exceptional formation is found above parent rock types of various composition namely, charnockite, leptynite, anorthosite and gabbro in Kerala. It is found over basalt in the states of Goa, Maharashtra and in some regions of Karnataka. In Gujarat in western India, impressive formations of laterite are found over granite, shale and sandstone..

Laterite is both a soil and a rock type rich in iron and aluminium and is commonly considered to have formed in hot and wet tropical areas. Nearly all laterites are of rusty-red coloration, because of high iron oxide content. They develop by intensive and prolonged weathering of the underlying parent rock, usually when there are conditions of high temperatures and heavy rainfall with alternate wet and dry periods. Tropical weathering (laterization) is a prolonged process of chemical weathering which produces a wide variety in the thickness, grade, chemistry and ore mineralogy of the resulting soils. The majority of the land area containing laterites is between the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn.

Operation Grasshopper was a project to look for natural resources in Suriname from the air. For this project, seven airstrips were constructed in the interior of Suriname from 1959 onward.

Geologically, Guinea is covered by a crust of a very large Archean West African Craton with its northern and western regions having formations of younger Proterozoic rocks and its eastern region consists greenstone belts under the Birimian Supergroup which account for a major portion of West Africa's gold and iron ore reserves. Weathering of paleozoïcs schists has resulted in laterisiation leading to the formation of very large bauxite deposits.

Medische Zending Primary Health Care Suriname, commonly known as Medische Zending or MZ is a Surinamese charitable organization offering primary healthcare to remote villages in the interior of Suriname.

The geology of Ivory Coast is almost entirely extremely ancient metamorphic and igneous crystalline basement rock between 2.1 and more than 3.5 billion years old, comprising part of the stable continental crust of the West African Craton. Near the surface, these ancient rocks have weathered into sediments and soils 20 to 45 meters thick on average, which holds much of Ivory Coast's groundwater. More recent sedimentary rocks are found along the coast. The country has extensive mineral resources such as gold, diamonds, nickel and bauxite as well as offshore oil and gas.

The geology of Sierra Leone is primarily very ancient Precambrian Archean and Proterozoic crystalline igneous and metamorphic basement rock, in many cases more than 2.5 billion years old. Throughout Earth history, Sierra Leone was impacted by major tectonic and climatic events, such as the Leonean, Liberian and Pan-African orogeny mountain building events, the Neoproterozoic Snowball Earth and millions of years of weathering, which has produced thick layers of regolith across much of the country's surface.

Paramacca is a resort in Suriname, located in the Sipaliwini District. The population is estimated between 1,500 and 2,000 people. In 1983, the Sipaliwini District was created, and the eastern part became the resort of Tapanahony. The Paramacca resort is the northern part of Tapanahony, and mainly inhabited by the Paramaccan people, the border of the resorts is the island of Bofoo Tabiki in the Marowijne River.

The De Goeje Mountains is a mountain range in the Sipaliwini District of Suriname. It is named after Claudius de Goeje.

Magneetrots is a mountain in the Sipaliwini District of Suriname. It measures 310 metres.

Onverdacht is a village in the resort of Zuid in the Para District of Suriname. Between 1941 and 2009, it was a bauxite mining town.