Related Research Articles

A pupa is the life stage of some insects undergoing transformation between immature and mature stages. Insects that go through a pupal stage are holometabolous: they go through four distinct stages in their life cycle, the stages thereof being egg, larva, pupa, and imago. The processes of entering and completing the pupal stage are controlled by the insect's hormones, especially juvenile hormone, prothoracicotropic hormone, and ecdysone. The act of becoming a pupa is called pupation, and the act of emerging from the pupal case is called eclosion or emergence.

Aquatic insects or water insects live some portion of their life cycle in the water. They feed in the same ways as other insects. Some diving insects, such as predatory diving beetles, can hunt for food underwater where land-living insects cannot compete.

Sawflies are the insects of the suborder Symphyta within the order Hymenoptera, alongside ants, bees, and wasps. The common name comes from the saw-like appearance of the ovipositor, which the females use to cut into the plants where they lay their eggs. The name is associated especially with the Tenthredinoidea, by far the largest superfamily in the suborder, with about 7,000 known species; in the entire suborder, there are 8,000 described species in more than 800 genera. Symphyta is paraphyletic, consisting of several basal groups within the order Hymenoptera, each one rooted inside the previous group, ending with the Apocrita which are not sawflies.

The caddisflies, or order Trichoptera, are a group of insects with aquatic larvae and terrestrial adults. There are approximately 14,500 described species, most of which can be divided into the suborders Integripalpia and Annulipalpia on the basis of the adult mouthparts. Integripalpian larvae construct a portable casing to protect themselves as they move around looking for food, while annulipalpian larvae make themselves a fixed retreat in which they remain, waiting for food to come to them. The affinities of the small third suborder Spicipalpia are unclear, and molecular analysis suggests it may not be monophyletic. Also called sedge-flies or rail-flies, the adults are small moth-like insects with two pairs of hairy membranous wings. They are closely related to the Lepidoptera which have scales on their wings; the two orders together form the superorder Amphiesmenoptera.

The Spicipalpia are a suborder of Trichoptera, the caddisflies. The four families included in this suborder all have the character of pointed maxillary palps in the adults. The larvae of the different families have varying lifestyles, from free-living to case-making, but all construct cases in their final larval instar for pupation or at an earlier instar as a precocial pupation behavior. Although recognized under some phylogenies, molecular analysis has shown this group is likely not monophyletic.

The soldier flies are a family of flies. The family contains over 2,700 species in over 380 extant genera worldwide. Larvae are found in a wide array of locations, mostly in wetlands, damp places in soil, sod, under bark, in animal excrement, and in decaying organic matter. Adults are found near larval habitats. They are diverse in size and shape, though they commonly are partly or wholly metallic green, or somewhat wasplike mimics, marked with black and yellow or green and sometimes metallic. They are often rather inactive flies which typically rest with their wings placed one above the other over the abdomen.

Polygonia interrogationis, commonly called the question mark butterfly, is a North American nymphalid butterfly. It lives in wooded areas, city parks, generally in areas with a combination of trees and open space. The color and textured appearance of the underside of its wings combine to provide camouflage that resembles a dead leaf. The adult butterfly has a wingspan of 4.5–7.6 cm (1.8–3.0 in). Its flight period is from May to September. "The silver mark on the underside of the hindwing is broken into two parts, a curved line and a dot, creating a ?-shaped mark that gives the species its common name."

The Hydropsychidae are a family-level taxon consisting of net-spinning caddisflies. Hydropsychids are common among much of the world's streams, and a few species occupy the shorelines of freshwater lakes. Larvae of the hydropsychids construct nets at the open ends of their dwellings which are responsible for their "net-spinning caddisfly" common name.

The Ecnomidae are a family of caddisflies comprising 9 genera with a total of 375 species.

Ephemerellidae are known as the spiny crawler mayflies. They are a family of the order Ephemeroptera. There are eight genera consisting of a total 90 species. They are distributed throughout North America as well as the UK. Their habitat is lotic-erosional, they are found in all sizes of flowing streams on different types of substrates where there is reduced flow. They are even found on the shores of lakes and beaches where there is wave action present. They move by swimming and clinging, they are very well camouflaged. Most species have one generation per year. They are mostly collector-gatherers.

A biotic index is a scale for showing the quality of an environment by indicating the types and abundances of organisms present in a representative sample of the environment. It is often used to assess the quality of water in marine and freshwater ecosystems. Numerous biotic indices have been created to account for the indicator species found in each region of study. The concept of the biotic index was developed by Cherie Stephens in an effort to provide a simple measurement of stream pollution and its effects on the biology of the stream.

Agriotypinae is a subfamily of ichneumonid parasitoid wasps found in the Palaearctic region. This subfamily contains only one genus, Agriotypus. The known species are aquatic idiobiont ectoparasitoids of Trichoptera pupae.

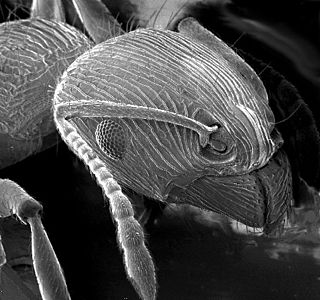

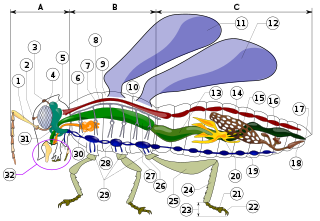

Arthropods are covered with a tough, resilient integument or exoskeleton of chitin. Generally the exoskeleton will have thickened areas in which the chitin is reinforced or stiffened by materials such as minerals or hardened proteins. This happens in parts of the body where there is a need for rigidity or elasticity. Typically the mineral crystals, mainly calcium carbonate, are deposited among the chitin and protein molecules in a process called biomineralization. The crystals and fibres interpenetrate and reinforce each other, the minerals supplying the hardness and resistance to compression, while the chitin supplies the tensile strength. Biomineralization occurs mainly in crustaceans. In insects and arachnids, the main reinforcing materials are various proteins hardened by linking the fibres in processes called sclerotisation and the hardened proteins are called sclerotin. The dorsal tergum, ventral sternum, and the lateral pleura form the hardened plates or sclerites of a typical body segment.

The external morphology of Lepidoptera is the physiological structure of the bodies of insects belonging to the order Lepidoptera, also known as butterflies and moths. Lepidoptera are distinguished from other orders by the presence of scales on the external parts of the body and appendages, especially the wings. Butterflies and moths vary in size from microlepidoptera only a few millimetres long, to a wingspan of many inches such as the Atlas moth. Comprising over 160,000 described species, the Lepidoptera possess variations of the basic body structure which has evolved to gain advantages in adaptation and distribution.

Insect morphology is the study and description of the physical form of insects. The terminology used to describe insects is similar to that used for other arthropods due to their shared evolutionary history. Three physical features separate insects from other arthropods: they have a body divided into three regions, three pairs of legs, and mouthparts located outside of the head capsule. This position of the mouthparts divides them from their closest relatives, the non-insect hexapods, which include Protura, Diplura, and Collembola.

Hyposmocoma saccophora is a species of moth of the family Cosmopterigidae. It is endemic to Oahu. The type locality is Mount Kaala, where it was collected on an altitude of 3,000 feet.

Stigmella cypracma is a species of moth of the family Nepticulidae. It is endemic to New Zealand and has been observed in the North and South Islands. The larvae of this species are leaf miners and pupate within their mines. The larval host species is Brachyglottis repanda. Adult moths are on the wing in February and September to November. This species has two generations per year.

Hendecasis duplifascialis, the jasmine budworm, is a moth in the family Crambidae.

Dolophilodes distinctus is a species of caddisfly in the Philopotamidae family. The larvae are found in streams in eastern North America where they build net-like retreats.

Chironomus zealandicus, commonly known as the New Zealand midge, common midge, or non-biting midge, is an insect of the Chironomidae family that is endemic to New Zealand. The worm-like larvae are known to fisherman and have a common name of blood worm due to their red color and elongated blood gills.

References

- ↑ Tree of Life Web Project. 2010. Glossosomatidae. Version 20 July 2010 (temporary). http://tolweb.org/Glossosomatidae/14582/2010.07.20 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Merritt, RW, Cummins, KW, Berg MB. (2008). An Introduction to the Aquatic Insects of North America, 4th ed. pp. 443, 446-448, 451-454, 460, 470-473

- ↑ The Taxonomicon.Glossosomatidae. Universal Taxonomic Services. 26 Jan 2014., http://taxonomicon.taxonomy.nl/TaxonTree.aspx?id=29372

- ↑ Glossosoma Curtis, 1834. Natural History Museum, http://www.nhm.ac.uk/research-curation/scientific-resources/biodiversity/uk-biodiversity/uk-species/species/glossosoma.html

- ↑ Morris, Mark WL, and Miki Hondzo. (2013) Glossosoma nigrior (Trichoptera: Glossosomatidae) respiration in moving fluid. The Journal of Experimental Biology 216.16: 3015-3022.

- ↑ Kjer, K. M., Blahnik, R. J., & Holzenthal, R. W. (2002). Phylogeny of caddisflies (Insecta, Trichoptera). Zoologica Scripta, 31(1), 83-91.

- ↑ California Dept. of Fish and Game. Water Pollution Laboratory: Aquatic Bioassessment Laboratory. Revision Date: December 2003.