The Great Chicago Fire was a conflagration that burned in the American city of Chicago during October 8–10, 1871. The fire killed approximately 300 people, destroyed roughly 3.3 square miles (9 km2) of the city including over 17,000 structures, and left more than 100,000 residents homeless. The fire began in a neighborhood southwest of the city center. A long period of hot, dry, windy conditions, and the wooden construction prevalent in the city, led to the conflagration. The fire leapt the south branch of the Chicago River and destroyed much of central Chicago and then leapt the main stem of the river, consuming the Near North Side.

Marinette is a city in and the county seat of Marinette County, Wisconsin, United States. It is located on the south bank of the Menominee River, at its mouth at Green Bay, part of Lake Michigan; to the north is Stephenson Island, part of the city preserved as park. During the lumbering boom of the late 19th century, Marinette became the tenth-largest city in Wisconsin in 1900, reaching a peak population of 16,195.

Green Bay is an arm of Lake Michigan, located along the south coast of Michigan's Upper Peninsula and the east coast of Wisconsin. It is separated from the rest of the lake by the Door Peninsula in Wisconsin, the Garden Peninsula in Michigan, and the chain of islands between them, all formed by the Niagara Escarpment. Green Bay is some 120 miles (193 km) long, with a width ranging from about 10 to 20 miles ; it is 1,626 square miles (4,210 km2) in area.

The Peshtigo fire was a large forest fire on October 8, 1871, in northeastern Wisconsin, United States, including much of the southern half of the Door Peninsula and adjacent parts of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. The largest community in the affected area was Peshtigo, Wisconsin, which had a population of approximately 1,700 residents. The fire burned about 1.2 million acres and is the deadliest wildfire in recorded history, with the number of deaths estimated between 1,500 and 2,500. Although the exact number of deaths is debated, mass graves, both those already exhumed and those still being discovered, in Peshtigo and the surrounding areas show that the death toll of the blaze was most likely greater than the 1889 Johnstown flood death toll of 2,200 people or more.

Peshtigo is a city in Marinette County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 3,420 at the 2020 census The city is surrounded by the Town of Peshtigo. It is part of the Marinette, WI–MI Micropolitan Statistical Area. Peshtigo is known for being the site of the Peshtigo fire of 1871, in which more than 1,200 people died.

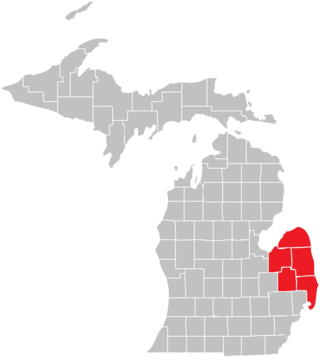

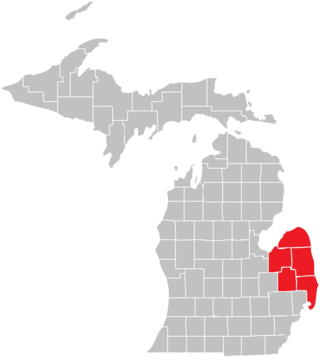

The Thumb Fire took place on September 5, 1881, in the Thumb area of Michigan in the United States. The fire, which burned over a million acres (4,000 km2) in less than a day, was the consequence of drought, hurricane-force winds, heat, the after-effects of the Port Huron Fire of 1871, and the ecological damage wrought by the era's logging techniques. The blaze, also called the Great Thumb Fire, the Great Forest Fire of 1881 and the Huron Fire, killed 282 people in Sanilac, Lapeer, Tuscola and Huron counties. The damage estimate was $2,347,000 in 1881, equivalent to $74,100,455 when adjusted for inflation. The fire sent enough soot and ash up into the atmosphere that sunlight was partially obscured at many locations on the East Coast of the United States. In New England cities, the sky appeared yellow and projected a strange luminosity onto buildings and vegetation. Twilight appeared at 12 noon. September 6, 1881, became known as Yellow Tuesday or Yellow Day because of the ominous nature of this atmospheric event.

Biela's Comet or Comet Biela was a periodic Jupiter-family comet first recorded in 1772 by Montaigne and Messier and finally identified as periodic in 1826 by Wilhelm von Biela. It was subsequently observed to split in two and has not been seen since 1852. As a result, it is currently considered to have been destroyed, although remnants have survived for some time as a meteor shower, the Andromedids which may show increased activity in 2023.

The Thumb is a region and a peninsula of the U.S. state of Michigan, so named because the Lower Peninsula is shaped like a mitten. The Thumb area is generally considered to be in the Central Michigan region, east of the Flint area and the Tri-Cities and north of Metro Detroit. The region is also branded as the Blue Water Area.

The Great Hinckley Fire was a conflagration in the pine forests of the U.S. state of Minnesota in September 1894, which burned an area of at least 200,000 acres, including the town of Hinckley. The official death count was 418; the actual number of fatalities was likely higher. Other sources put the death toll at 476.

The Port Huron Fire of October 8, 1871 burned a number of cities including White Rock and Port Huron, and much of the countryside in the "Thumb" region of the U.S. state of Michigan.

The Great Fire of 1871 may refer to any of several large fires in the Midwestern United States that began on October 8, 1871:

The Baudette fire, also known as the Spooner–Baudette fire, was a large wildfire on October 7, 1910 that burned 1,200 to 1,450 square kilometres in Beltrami County, Minnesota, including nearly all of the twin towns of Spooner and Baudette. The fire also burned the villages of Graceton, Pitt, Williams, and Cedar Spur, Minnesota. Damage was horrific yet less so in the communities of Zipple, Roosevelt, Swift and Warroad in the U.S. and Stratton, Pinewood, Rainy River, and Sprague across the river in Canada, which also suffered losses. The Town of Rainy River lost its lumber mill, but saved many of the residents of Baudette and Spooner since the residential area was not affected. Their American friends were welcomed into homes where they remained for a very long time as their homes had to be rebuilt, creating a strong bond between the two communities.

The Green Island Light is a lighthouse located on Green Island in Green Bay. Abandoned since its deactivation in 1956, it survives as a hollow shell near the existing skeleton tower.

Menekaunee, Wisconsin, also spelled Minikani or Menekaune, was a village in Marinette County, Wisconsin, United States; it is now a neighborhood of the City of Marinette.

Orin William Angwall or Orin W. Angwall was an American lake captain, commercial fisherman, and politician. He served in the Wisconsin legislature and was mayor of Marinette.

Jean-Pierre Pernin, also known as Peter Pernin in America, was a French Roman Catholic priest, who came to the United States in 1864 as a missionary, working in Illinois, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. As Catholic pastor of Peshtigo, Wisconsin, he survived the Peshtigo fire on October 8–9, 1871. His survivor's memoir, written originally in French, published simultaneously in English translation, and entitled Le doigt de Dieu est là! / The Finger of God Is There!, is a document important to the history of the fire.

The Wisconsin & Michigan Railway (W&M) was incorporated October 26, 1893, under the general laws of Wisconsin for the purpose of constructing, maintaining, and operating a railroad as described in its articles of incorporation.

The climate of Door County, Wisconsin is tempered by Green Bay and Lake Michigan. There are fewer extremely cold days and fewer hot days than in areas of Wisconsin directly to the west. Lake waters delay the coming of spring as well as extend mild temperatures in the fall. Annual precipitation is slightly lower than elsewhere in northern Wisconsin. The county features a humid continental climate with warm summers and cold snowy winters.

The Great Fires of 1871 were a series of conflagrations that took place throughout the final days of September and first weeks of October 1871 in the United States, primarily targeting the Midwestern United States. These fires include the Great Chicago Fire, Peshtigo Fire, and Great Michigan Fire. In total, the fires burnt more than 3,000,000 acres of land and killed thousands.