Histoplasmosis is a fungal infection caused by Histoplasma capsulatum. Symptoms of this infection vary greatly, but the disease affects primarily the lungs. Occasionally, other organs are affected; called disseminated histoplasmosis, it can be fatal if left untreated.

Talaromyces marneffei, formerly called Penicillium marneffei, was identified in 1956. The organism is endemic to southeast Asia where it is an important cause of opportunistic infections in those with HIV/AIDS-related immunodeficiency. Incidence of T. marneffei infections has increased due to a rise in HIV infection rates in the region.

A granuloma is an aggregation of macrophages that forms in response to chronic inflammation. This occurs when the immune system attempts to isolate foreign substances that it is otherwise unable to eliminate. Such substances include infectious organisms including bacteria and fungi, as well as other materials such as foreign objects, keratin, and suture fragments.

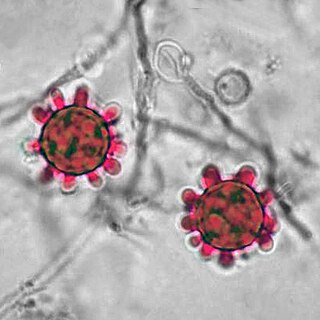

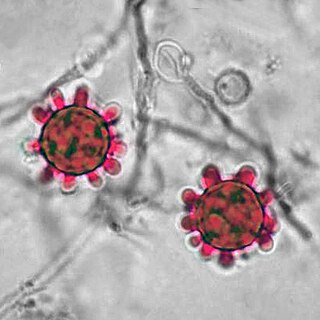

Blastomycosis, also known as Gilchrist's disease, is a fungal infection, typically of the lungs, which can spread to brain, stomach, intestine and skin, where it appears as crusting purplish warty plaques with a roundish bumpy edge and central depression. Only about half of people with the disease have symptoms, which can include fever, cough, night sweats, muscle pains, weight loss, chest pain, and fatigue. Symptoms usually develop between three weeks and three months after breathing in the spores. In 25% to 40% of cases, the infection also spreads to other parts of the body, such as the skin, bones or central nervous system. Although blastomycosis is especially dangerous for those with weak immune systems, most people diagnosed with blastomycosis have healthy immune systems.

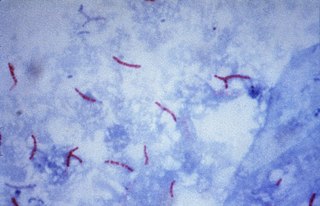

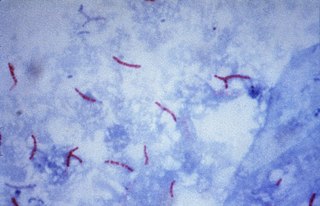

The Ziehl-Neelsen stain, also known as the acid-fast stain, is a bacteriological staining technique used in cytopathology and microbiology to identify acid-fast bacteria under microscopy, particularly members of the Mycobacterium genus. This staining method was initially introduced by Paul Ehrlich (1854–1915) and subsequently modified by the German bacteriologists Franz Ziehl (1859–1926) and Friedrich Neelsen (1854–1898) during the late 19th century.

An opportunistic infection is an infection caused by pathogens that take advantage of an opportunity not normally available. These opportunities can stem from a variety of sources, such as a weakened immune system, an altered microbiome, or breached integumentary barriers. Many of these pathogens do not necessarily cause disease in a healthy host that has a non-compromised immune system, and can, in some cases, act as commensals until the balance of the immune system is disrupted. Opportunistic infections can also be attributed to pathogens which cause mild illness in healthy individuals but lead to more serious illness when given the opportunity to take advantage of an immunocompromised host.

Presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome (POHS) is a syndrome affecting the eye, which is characterized by peripheral atrophic chorioretinal scars, atrophy or scarring adjacent to the optic disc and maculopathy.

Histoplasma is a genus of fungi in the order Onygenales. Species are known human pathogens producing yeast-like states under pathogenic conditions. They are the causative agents of histoplasmosis in humans and epizootic lymphangitis in horses.

Blastomyces dermatitidis is a dimorphic fungus that causes blastomycosis, an invasive and often serious fungal infection found occasionally in humans and other animals. It lives in soil and wet, decaying wood, often in an area close to a waterway such as a lake, river or stream. Indoor growth may also occur, for example, in accumulated debris in damp sheds or shacks. The fungus is endemic to parts of eastern North America, particularly boreal northern Ontario, southeastern Manitoba, Quebec south of the St. Lawrence River, parts of the U.S. Appalachian mountains and interconnected eastern mountain chains, the west bank of Lake Michigan, the state of Wisconsin, and the entire Mississippi Valley including the valleys of some major tributaries such as the Ohio River. In addition, it occurs rarely in Africa both north and south of the Sahara Desert, as well as in the Arabian Peninsula and the Indian subcontinent. Though it has never been directly observed growing in nature, it is thought to grow there as a cottony white mold, similar to the growth seen in artificial culture at 25 °C (77 °F). In an infected human or animal, however, it converts in growth form and becomes a large-celled budding yeast. Blastomycosis is generally readily treatable with systemic antifungal drugs once it is correctly diagnosed; however, delayed diagnosis is very common except in highly endemic areas.

Dimorphic fungi are fungi that can exist in the form of both mold and yeast. This is usually brought about by change in temperature and the fungi are also described as thermally dimorphic fungi. An example is Talaromyces marneffei, a human pathogen that grows as a mold at room temperature, and as a yeast at human body temperature.

Guano is the accumulated excrement of seabirds or bats. Guano is a highly effective fertilizer due to the high content of nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium, all key nutrients essential for plant growth. Guano was also, to a lesser extent, sought for the production of gunpowder and other explosive materials.

Pathogenic fungi are fungi that cause disease in humans or other organisms. Although fungi are eukaryotic, many pathogenic fungi are microorganisms. Approximately 300 fungi are known to be pathogenic to humans; their study is called "medical mycology". Fungal infections are estimated to kill more people than either tuberculosis or malaria—about two million people per year.

Fungal meningitis refers to meningitis caused by a fungal infection.

African histoplasmosis is a fungal infection caused by Histoplasma capsulatumvar. duboisii, or Histoplama duboisii (Hcd). Disease has been most often reported in Uganda, Nigeria, Zaire and Senegal, as Hcd is exclusive to Africa. In human disease it manifests differently than histoplasmosis, most often involving the skin and bones and rarely involving the lungs. Also unlike Hcc, Hcd has been reported to rarely present in those with HIV, likely due to underreporting. However, this along with the differences in Hcc and Hcd have been disputed.

Ajellomyces is a genus of fungi in the division Ascomycota, in the family Ajellomycetaceae. The genus contains two species, which have a widespread distribution, especially in tropical areas. The species Ajellomyces capsulatus is significant to human health as the causative agent of histoplasmosis. This species is more usually referred to as Histoplasma capsulatum, with the designation Ajellomyces capsulatus referring to the ascomycetous perfect stage.

Emmonsia parva is a filamentous, saprotrophic fungus and one of three species within the genus Emmonsia. The fungus is most known for its causal association with the lung disease, adiaspiromycosis which occurs most commonly in small mammals but is also seen in humans. The disease was first described from rodents in Arizona, and the first human case was reported in France in 1964. Since then, the disease has been reported from Honduras, Brazil, the Czech Republic, Russia, the United States of America and Guatemala. Infections in general are quite rare, especially in humans.

Histoplasma duboisii is a saprotrophic fungus responsible for the invasive infection known as African histoplasmosis. This species is a close relative of Histoplasma capsulatum, the agent of classical histoplasmosis, and the two occur in similar habitats. Histoplasma duboisii is restricted to continental Africa and Madagascar, although scattered reports have arisen from other places usually in individuals with an African travel history. Like, H. capsulatum, H. duboisii is dimorphic – growing as a filamentous fungus at ambient temperature and a yeast at body temperature. It differs morphologically from H. capsulatum by the typical production of a large-celled yeast form. Both agents cause similar forms of disease, although H. duboisii predominantly causes cutaneous and subcutaneous disease in humans and non-human primates. The agent responds to many antifungal drug therapies used to treat serious fungal diseases.

Emmonsiosis, also known as emergomycosis, is a systemic fungal infection that can affect the lungs, generally always affects the skin and can become widespread. The lesions in the skin look like small red bumps and patches with a dip, ulcer and dead tissue in the centre.

Chester Wilson Emmons was an American scientist, who researched fungi that cause diseases. He was the first mycologist at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), where for 31 years he served as head of its Medical Mycology Section.

Libero Ajello was an American mycologist. He cofounded and was first president of the International Society of Human and Animal Mycology (ISHAM). He was the head of the Division of Mycotic Diseases at the Communicable Disease Center (CDC), and editor of the ISHAM Journal Medical Mycology for several years. He was one of the first researchers to investigate histoplasmosis and coccidioidomycosis in the United States and made valuable contributions to the comprehensive field of veterinary and human fungal disease diagnosis.