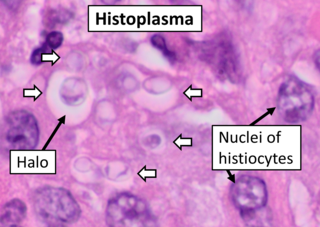

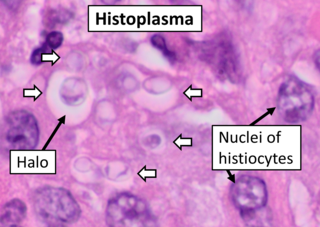

Histoplasmosis is a fungal infection caused by Histoplasma capsulatum. Symptoms of this infection vary greatly, but the disease affects primarily the lungs. Occasionally, other organs are affected; called disseminated histoplasmosis, it can be fatal if left untreated.

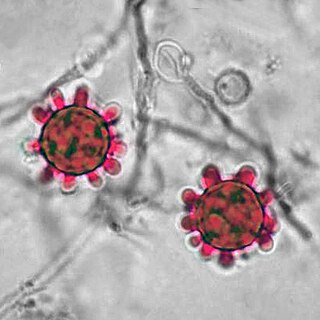

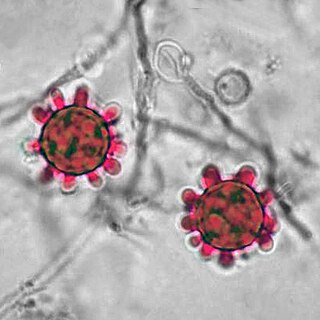

Talaromyces marneffei, formerly called Penicillium marneffei, was identified in 1956. The organism is endemic to southeast Asia, where it is an important cause of opportunistic infections in those with HIV/AIDS-related immunodeficiency. Incidence of T. marneffei infections has increased due to a rise in HIV infection rates in the region.

Fungal infection, also known as mycosis, is a disease caused by fungi. Different types are traditionally divided according to the part of the body affected; superficial, subcutaneous, and systemic. Superficial fungal infections include common tinea of the skin, such as tinea of the body, groin, hands, feet and beard, and yeast infections such as pityriasis versicolor. Subcutaneous types include eumycetoma and chromoblastomycosis, which generally affect tissues in and beneath the skin. Systemic fungal infections are more serious and include cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, pneumocystis pneumonia, aspergillosis and mucormycosis. Signs and symptoms range widely. There is usually a rash with superficial infection. Fungal infection within the skin or under the skin may present with a lump and skin changes. Pneumonia-like symptoms or meningitis may occur with a deeper or systemic infection.

An opportunistic infection is an infection caused by pathogens that take advantage of an opportunity not normally available. These opportunities can stem from a variety of sources, such as a weakened immune system, an altered microbiome, or breached integumentary barriers. Many of these pathogens do not necessarily cause disease in a healthy host that has a non-compromised immune system, and can, in some cases, act as commensals until the balance of the immune system is disrupted. Opportunistic infections can also be attributed to pathogens which cause mild illness in healthy individuals but lead to more serious illness when given the opportunity to take advantage of an immunocompromised host.

Histoplasma is a genus of fungi in the order Onygenales. Species are known human pathogens producing yeast-like states under pathogenic conditions. They are the causative agents of histoplasmosis in humans and epizootic lymphangitis in horses.

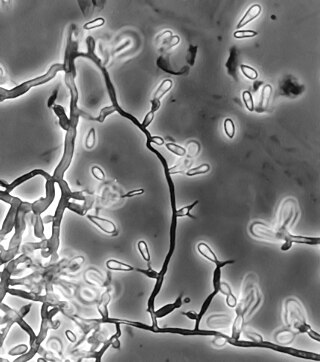

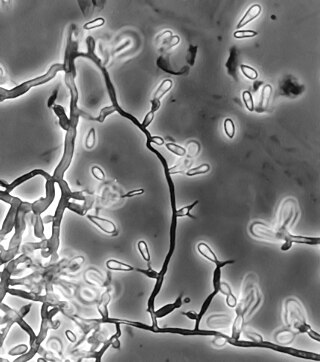

Sporothrix schenckii, a fungus that can be found worldwide in the environment, is named for medical student Benjamin Schenck, who in 1896 was the first to isolate it from a human specimen. The species is present in soil as well as in and on living and decomposing plant material such as peat moss. It can infect humans as well as animals and is the causative agent of sporotrichosis, commonly known as "rose handler's disease." The most common route of infection is the introduction of spores to the body through a cut or puncture wound in the skin. Infection commonly occurs in otherwise healthy individuals but is rarely life-threatening and can be treated with antifungals. In the environment it is found growing as filamentous hyphae. In host tissue it is found as a yeast. The transition between the hyphal and yeast forms is temperature dependent making S. schenckii a thermally dimorphic fungus.

Histoplasma capsulatum is a species of dimorphic fungus. Its sexual form is called Ajellomyces capsulatus. It can cause pulmonary and disseminated histoplasmosis.

Exophiala jeanselmei is a saprotrophic fungus in the family Herpotrichiellaceae. Four varieties have been discovered: Exophiala jeanselmei var. heteromorpha, E. jeanselmei var. lecanii-corni, E. jeanselmei var. jeanselmei, and E. jeanselmei var. castellanii. Other species in the genus Exophiala such as E. dermatitidis and E. spinifera have been reported to have similar annellidic conidiogenesis and may therefore be difficult to differentiate.

Dimorphic fungi are fungi that can exist in the form of both mold and yeast. This is usually brought about by change in temperature and the fungi are also described as thermally dimorphic fungi. An example is Talaromyces marneffei, a human pathogen that grows as a mold at room temperature, and as a yeast at human body temperature.

Pathogenic fungi are fungi that cause disease in humans or other organisms. Although fungi are eukaryotic, many pathogenic fungi are microorganisms. Approximately 300 fungi are known to be pathogenic to humans; their study is called "medical mycology". Fungal infections are estimated to kill more people than either tuberculosis or malaria—about two million people per year.

Saksenaea vasiformis is an infectious fungus associated with cutaneous or subcutaneous lesions following trauma. It causes opportunistic infections as the entry of the fungus is through open spaces of cutaneous barrier ranging in severity from mild to severe or fatal. It lives in soils worldwide, but is considered as a rare human pathogen since only 38 cases were reported as of 2012. Saksenaea vasiformis usually fails to sporulate on the routine culture media, creating a challenge for early diagnosis, which is essential for a good prognosis. Infections are usually treated using a combination of amphotericin B and surgery. Saksenaea vasiformis is one of the few fungi known to cause necrotizing fasciitis or "flesh-eating disease".

African histoplasmosis is a fungal infection caused by Histoplasma capsulatumvar. duboisii, or Histoplama duboisii (Hcd). Disease has been most often reported in Uganda, Nigeria, Zaire and Senegal, as Hcd is exclusive to Africa. In human disease it manifests differently than histoplasmosis, most often involving the skin and bones and rarely involving the lungs. Also unlike Hcc, Hcd has been reported to rarely present in those with HIV, likely due to underreporting. However, this along with the differences in Hcc and Hcd have been disputed.

Ochroconis gallopava, also called Dactylaria gallopava or Dactylaria constricta var. gallopava, is a member of genus Dactylaria. Ochroconis gallopava is a thermotolerant, darkly pigmented fungus that causes various infections in fowls, turkeys, poults, and immunocompromised humans first reported in 1986. Since then, the fungus has been increasingly reported as an agent of human disease especially in recipients of solid organ transplants. Ochroconis gallopava infection has a long onset and can involve a variety of body sites. Treatment of infection often involves a combination of antifungal drug therapy and surgical excision.

Phaeohyphomycosis is a diverse group of fungal infections, caused by dematiaceous fungi whose morphologic characteristics in tissue include hyphae, yeast-like cells, or a combination of these. It can be associated with an array of melanistic filamentous fungi including Alternaria species, Exophiala jeanselmei, and Rhinocladiella mackenziei.

Scedosporiosis is the general name for any mycosis – i.e., fungal infection – caused by a fungus from the genus Scedosporium. Current population-based studies suggest Scedosporium prolificans and Scedosporium apiospermum to be among the most common infecting agents from the genus, although infections caused by other members thereof are not unheard of. The latter is an asexual form (anamorph) of another fungus, Pseudallescheria boydii. The former is a "black yeast", currently not characterized as well, although both of them have been described as saprophytes.

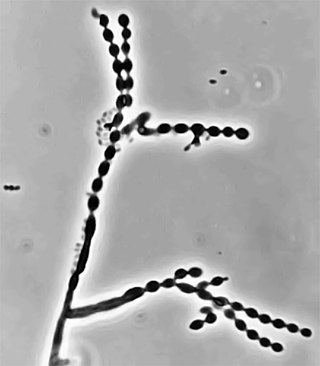

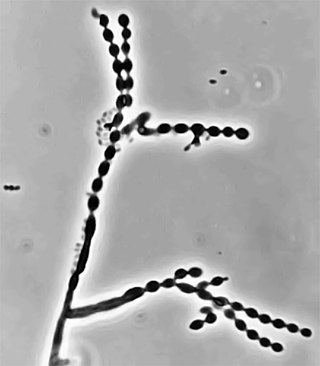

Cladophialophora carrionii is a melanized fungus in the genus Cladophialophora that is associated with decaying plant material like cacti and wood. It is one of the most frequent species of Cladophialophora implicated in human disease. Cladophialophora carrionii is a causative agent of chromoblastomycosis, a subcutaneous infection that occurs in sub-tropical areas such as Madagascar, Australia and northwestern Venezuela. Transmission occurs through traumatic implantation of plant material colonized by C. carrionii, mainly infecting rural workers. When C. carrionii infects its host, it transforms from a mycelial state to a muriform state to better tolerate the extreme conditions in the host's body.

Phialophora verrucosa is a pathogenic, dematiaceous fungus that is a common cause of chromoblastomycosis. It has also been reported to cause subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis and mycetoma in very rare cases. In the natural environment, it can be found in rotting wood, soil, wasp nests, and plant debris. P. verrucosa is sometimes referred to as Phialophora americana, a closely related environmental species which, along with P. verrucosa, is also categorized in the P. carrionii clade.

Arthrographis kalrae is an ascomycetous fungus responsible for human nail infections described in 1938 by Cochet as A. langeronii. A. kalrae is considered a weak pathogen of animals including human restricted to the outermost keratinized layers of tissue. Infections caused by this species are normally responsive to commonly used antifungal drugs with only very rare exceptions.

Emmonsiosis, also known as emergomycosis, is a systemic fungal infection that can affect the lungs, generally always affects the skin and can become widespread. The lesions in the skin look like small red bumps and patches with a dip, ulcer and dead tissue in the centre.

Sporothrix brasiliensis is a fungus that is commonly found in soil. It is an emerging fungal pathogen that is causing disease in humans and cats mainly in Brazil and other countries in South America.