Related Research Articles

Gay bashing is an attack, abuse, or assault committed against a person who is perceived by the aggressor to be gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender or queer (LGBTQ+). It includes both violence against LGBT people and LGBT bullying. The term covers violence against and bullying of people who are LGBT, as well as non-LGBT people whom the attacker perceives to be LGBT.

The field of psychology has extensively studied homosexuality as a human sexual orientation. The American Psychiatric Association listed homosexuality in the DSM-I in 1952 as a "sociopathic personality disturbance," but that classification came under scrutiny in research funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. That research and subsequent studies consistently failed to produce any empirical or scientific basis for regarding homosexuality as anything other than a natural and normal sexual orientation that is a healthy and positive expression of human sexuality. As a result of this scientific research, the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from the DSM-II in 1973. Upon a thorough review of the scientific data, the American Psychological Association followed in 1975 and also called on all mental health professionals to take the lead in "removing the stigma of mental illness that has long been associated" with homosexuality. In 1993, the National Association of Social Workers adopted the same position as the American Psychiatric Association and the American Psychological Association, in recognition of scientific evidence. The World Health Organization, which listed homosexuality in the ICD-9 in 1977, removed homosexuality from the ICD-10 which was endorsed by the 43rd World Health Assembly on 17 May 1990.

Obtaining precise numbers on the demographics of sexual orientation is difficult for a variety of reasons, including the nature of the research questions. Most of the studies on sexual orientation rely on self-reported data, which may pose challenges to researchers because of the subject matter's sensitivity. The studies tend to pose two sets of questions. One set examines self-report data of same-sex sexual experiences and attractions, while the other set examines self-report data of personal identification as homosexual or bisexual. Overall, fewer research subjects identify as homosexual or bisexual than report having had sexual experiences or attraction to a person of the same sex. Survey type, questions and survey setting may affect the respondents' answers.

LGBTQ culture is a culture shared by lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer individuals. It is sometimes referred to as queer culture, while the term gay culture may be used to mean either "LGBT culture" or homosexual culture specifically.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) personnel are able to serve in the armed forces of some countries around the world: the vast majority of industrialized, Western countries including some South American countries, such as Argentina, Brazil and Chile in addition to other countries, such as the United States, Canada, Japan, Australia, Mexico, France, Finland, Denmark and Israel. The rights concerning intersex people are more vague.

A sexual minority is a demographic whose sexual identity, orientation or practices differ from the majority of the surrounding society. Primarily used to refer to lesbian, gay, bisexual, or non-heterosexual individuals, it can also refer to transgender, non-binary or intersex individuals.

LGBT stereotypes are stereotypes about lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBTQ) people based on their sexual orientations, gender identities, or gender expressions. Stereotypical perceptions may be acquired through interactions with parents, teachers, peers and mass media, or, more generally, through a lack of firsthand familiarity, resulting in an increased reliance on generalizations.

The questioning of one's sexual orientation, sexual identity, gender, or all three is a process of exploration by people who may be unsure, still exploring, or concerned about applying a social label to themselves for various reasons. The letter "Q" is sometimes added to the end of the acronym LGBT ; the "Q" can refer to either queer or questioning.

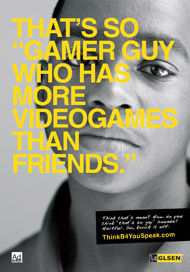

The Think Before You Speak campaign is a television, radio, and magazine advertising campaign launched in 2008 and developed to raise awareness of the common use of derogatory vocabulary among youth towards lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning (LGBTQ) people. It also aims to "raise awareness about the prevalence and consequences of anti-LGBTQ bias and behaviour in America's schools." As LGBTQ people have become more accepted in the mainstream culture, more studies have confirmed that they are one of the most targeted groups for harassment and bullying. An "analysis of 14 years of hate crime data" by the FBI found that gays and lesbians, or those perceived to be gay, "are far more likely to be victims of a violent hate crime than any other minority group in the United States". "As Americans become more accepting of LGBT people, the most extreme elements of the anti-gay movement are digging in their heels and continuing to defame gays and lesbians with falsehoods that grow more incendiary by the day," said Mark Potok, editor of the Intelligence Report. "The leaders of this movement may deny it, but it seems clear that their demonization of gays and lesbians plays a role in fomenting the violence, hatred and bullying we're seeing." Because of their sexual orientation or gender identity/expression, nearly half of LGBTQ students have been physically assaulted at school. The campaign takes positive steps to counteract hateful and anti-gay speech that LGBTQ students experience in their daily lives in hopes to de-escalate the cycle of hate speech/harassment/bullying/physical threats and violence.

Various issues in medicine relate to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people. According to the US Gay and Lesbian Medical Association (GLMA), besides HIV/AIDS, issues related to LGBT health include breast and cervical cancer, hepatitis, mental health, substance use disorders, alcohol use, tobacco use, depression, access to care for transgender persons, issues surrounding marriage and family recognition, conversion therapy, refusal clause legislation, and laws that are intended to "immunize health care professionals from liability for discriminating against persons of whom they disapprove."

Research has found that attempted suicide rates and suicidal ideation among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) youth are significantly higher than among the general population.

Ali He'shun Forney was an African-American gay and gender non-conforming transgender youth who also used the name Luscious.

Youth pride, an extension of the Gay pride and LGBT social movements, promotes equality amongst young members of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex, and Queer (LGBTIQ+) community. The movement exists in many countries and focuses mainly on festivals and parades, enabling many LGBTIQ+ youth to network, communicate, and celebrate their gender and sexual identities.

The demographics of sexual orientation and gender identity in the United States have been studied in the social sciences in recent decades. A 2022 Gallup poll concluded that 7.1% of adult Americans identified as LGBT. A different survey in 2016, from the Williams Institute, estimated that 0.6% of U.S. adults identify as transgender. As of 2022, estimates for the total percentage of U.S. adults that are transgender or nonbinary range from 0.5% to 1.6%. Additionally, a Pew Research survey from 2022 found that approximately 5% of young adults in the U.S. say their gender is different from their sex assigned at birth.

The following outline offers an overview and guide to LGBTQ topics:

LGBT ageing addresses issues and concerns related to the ageing of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people. Older LGBT people are marginalised by: a) younger LGBT people, because of ageism; and b) by older age social networks because of homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, heteronormativity, heterosexism, prejudice and discrimination towards LGBT people.

LGBTQ psychology is a field of psychology of surrounding the lives of LGBTQ+ individuals, in the particular the diverse range of psychological perspectives and experiences of these individuals. It covers different aspects such as identity development including the coming out process, parenting and family practices and support for LGBTQ+ individuals, as well as issues of prejudice and discrimination involving the LGBTQ community.

Due to the increased vulnerability that lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth face compared to their non-LGBT peers, there are notable differences in the mental and physical health risks tied to the social interactions of LGBT youth compared to the social interactions of heterosexual youth. Youth of the LGBT community experience greater encounters with not only health risks, but also violence and bullying, due to their sexual orientation, self-identification, and lack of support from institutions in society.

Sexual assault of LGBT people, also known as sexual and gender minorities (SGM), is a form of violence that occurs within the LGBT community. While sexual assault and other forms of interpersonal violence can occur in all forms of relationships, it is found that sexual minorities experience it at rates that are equal to or higher than their heterosexual counterparts. There is a lack of research on this specific problem for the LGBT population as a whole, but there does exist a substantial amount of research on college LGBT students who have experienced sexual assault and sexual harassment.

People who are LGBT are significantly more likely than those who are not to experience depression, PTSD, and generalized anxiety disorder.

References

- Christiani, A., Hudson, A. L., Nyamathi, A., Mutere, M., & Sweat, J. (2008). Attitudes of Homeless and Drug-Using Youth Regarding Barriers and Facilitators in Delivery of Quality and Culturally Sensitive Health Care. Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 21(3), 154–163. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6171.2008.00139.x

- Cochran, B. N., Stewart, A. J., Ginzler, J. A., & Cauce, A. (2002). Challenges Faced by Homeless Sexual Minorities: Comparison of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Homeless Adolescents With Their Heterosexual Counterparts. American Journal of Public Health, 92(5), 773–777.

- Corliss, H. L., Goodenow, C. S., Nichols, L., & Austin, S. (2011). High Burden of Homelessness Among Sexual-Minority Adolescents: Findings From a Representative Massachusetts High School Sample. American Journal of Public Health, 101(9), 1683–1689. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300155

- Durso, L. E., & Gates, G. J. (2012). Serving Our Youth: Findings from a National Survey of Services Providers Working with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth Who Are Homeless or At Risk of Becoming Homeless. The Williams Institute.

- Gangamma, R., Slesnick, N., Toviessi, P., & Serovich, J. (2008). Comparison of HIV Risks among Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Heterosexual Homeless Youth. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 37(4), 456–464. doi:10.1007/s10964-007-9171-9

- Hunter, E. (2008). What's Good for the Gays is Good for the Gander: Making Homeless Youth Housing Safer for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth. Family Court Review, 46(3), 543–557. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1617.2008.00220.x

- Mottet, L., & Ohle, J. M. (2003). Transitioning Our Shelters: A Guide to Making Homeless Shelters Safe for Transgender People. National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.

- Quintana, N. S., Rosenthal, J., & Krehley, J. (2010). On the Streets. Center for American Progress.

- Ray, Nicholas, and Colby Berger. Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth: An epidemic of homelessness. National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute, 2007.

- Rew, L., Whittaker, T. A., Taylor-Seehafer, M. A., & Smith, L. R. (2005). Sexual Health Risks and Protective Resources in Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Heterosexual Homeless Youth. Journal For Specialists In Pediatric Nursing, 10(1), 11–19.

- Van Leeuwen, J. M., Boyle, S., Salomonsen-Sautel, S., Baker, D. N., Garcia, J. T., Hoffman, A., & Hopfer, C. J. (2006). Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Homeless Youth: An Eight-City Public Health Perspective. Child Welfare, 85(2), 151–170.

- Ventimiglia, N. (2012). “LGBT Selective Victimization: Unprotected Youth on the Streets.” Journal of Law in Society, 13(2): 439–453.

- Whitbeck, Les B.; Chen, Xiaojin; Hoyt, Dan R.; Tyler, Kimberly; and Johnson, Kurt D., "Mental Disorder, Subsistence Strategies, and Victimization among Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Homeless and Runaway Adolescents" (2004). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. Paper 53.