The euro is the official currency of 20 of the 27 member states of the European Union. This group of states is officially known as the euro area or, commonly, the eurozone, and includes about 344 million citizens as of 2023. The euro is divided into 100 euro cents.

The economy of Hungary is a high-income mixed economy, ranked as the 9th most complex economy according to the Economic Complexity Index. Hungary is a member of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) with a very high human development index and a skilled labour force, with the 22nd lowest income inequality by Gini index in the world. The Hungarian economy is the 53rd-largest economy in the world with $265.037 billion annual output, and ranks 41st in the world in terms of GDP per capita measured by purchasing power parity. Hungary has an export-oriented market economy with a heavy emphasis on foreign trade; thus the country is the 35th largest export economy in the world. The country had more than $100 billion of exports in 2015, with a high trade surplus of $9.003 billion, of which 79% went to the European Union (EU) and 21% was extra-EU trade. Hungary's productive capacity is more than 80% privately owned, with 39.1% overall taxation, which funds the country's welfare economy. On the expenditure side, household consumption is the main component of GDP and accounts for 50% of its total, followed by gross fixed capital formation with 22% and government expenditure with 20%.

The economy of Romania is a complex high-income economy with a skilled labour force, ranked 12th in the European Union by total nominal GDP and 7th largest when adjusted by purchasing power parity. The World Bank notes that Romania's efforts are focused on accelerating structural reforms and strengthening institutions in order to further converge with the European Union. The country's economic growth has been one of the highest in the EU since 2010, with 2022 seeing a better-than-expected 4.8% increase.

The euro area, commonly called the eurozone (EZ), is a currency union of 20 member states of the European Union (EU) that have adopted the euro (€) as their primary currency and sole legal tender, and have thus fully implemented EMU policies.

The European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II) is a system introduced by the European Economic Community on 1 January 1999 alongside the introduction of a single currency, the euro as part of the European Monetary System (EMS), to reduce exchange rate variability and achieve monetary stability in Europe.

The economy of the European Union is the joint economy of the member states of the European Union (EU). It is the second largest economy in the world in nominal terms, after the United States and the third one in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms, after China and the United States. The European Union's GDP estimated to be around $19.35 trillion (nominal) in 2024 representing around one sixth of the global economy. Germany has the biggest national GDP of all EU countries, followed by France and Italy.

The euro convergence criteria are the criteria European Union member states are required to meet to enter the third stage of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) and adopt the euro as their currency. The four main criteria, which actually comprise five criteria as the "fiscal criterion" consists of both a "debt criterion" and a "deficit criterion", are based on Article 140 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

Lithuania, as an EU member state, joined the eurozone by adopting the euro on 1 January 2015. This made it the last of the three Baltic states to adopt the euro, after Estonia (2011) and Latvia (2014). Before then, its currency, the litas, was pegged to the euro at 3.4528 litas to 1 euro.

The Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) is an indicator of inflation and price stability for the European Central Bank (ECB). It is a consumer price index which is compiled according to a methodology that has been harmonised across EU countries. The euro area HICP is a weighted average of price indices of member states who have adopted the euro. The primary goal of the ECB is to maintain price stability, defined as keeping the year on year increase HICP target on 2% over the medium term. In order to do that, the ECB can control the short-term interest rate through Eonia, the European overnight index average, which affects market expectations. The HICP is also used to assess the convergence criteria on inflation which countries must fulfill in order to adopt the euro. In the United Kingdom, the HICP is called the CPI and is used to set the inflation target of the Bank of England.

The Czech Republic is bound to adopt the euro in the future and to join the eurozone once it has satisfied the euro convergence criteria by the Treaty of Accession since it joined the European Union (EU) in 2004. The Czech Republic is therefore a candidate for the enlargement of the eurozone and it uses the Czech koruna as its currency, regulated by the Czech National Bank, a member of the European System of Central Banks, and does not participate in European Exchange Rate Mechanism II.

Latvia replaced its previous currency, the lats, with the euro on 1 January 2014, after a European Union (EU) assessment in June 2013 asserted that the country had met all convergence criteria necessary for euro adoption. The adoption process began 1 May 2004, when Latvia joined the European Union, entering the EU's Economic and Monetary Union. At the start of 2005, the lats was pegged to the euro at Ls 0.702804 = €1, and Latvia joined the European Exchange Rate Mechanism, four months later on 2 May 2005.

Poland does not use the euro as its currency. However, under the terms of their Treaty of Accession with the European Union, all new Member States "shall participate in the Economic and Monetary Union from the date of accession as a Member State with a derogation", which means that Poland is obliged to eventually replace its currency, the złoty, with the euro.

Bulgaria plans to adopt the euro and become the 21st member state of the eurozone. The Bulgarian lev has been on the currency board since 1997 through a fixed exchange rate of the lev against the Deutsche Mark and the euro. Bulgaria's target date for introduction of the euro is 1 January 2025, which would make the euro only the second national currency of the country since the lev was introduced over 140 years ago. The official exchange rate is 1.95583 lev for 1 euro.

Romania's national currency is the leu. After Romania joined the European Union (EU) in 2007, the country became required to replace the leu with the euro once it meets all four euro convergence criteria, as stated in article 140 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. As of 2023, the only currency on the market is the leu and the euro is not yet used in shops. The Romanian leu is not part of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism, although Romanian authorities are working to prepare the changeover to the euro. To achieve the currency changeover, Romania must undergo at least two years of stability within the limits of the convergence criteria. The current Romanian government established a self-imposed criterion to reach a certain level of real convergence as a steering anchor to decide the appropriate target year for ERM II membership and Euro adoption. In March 2018, the National Plan for the Adoption of the Euro scheduled the date for euro adoption in Romania as 2024. Nevertheless, in early 2021, this date was postponed to 2027 or 2028, and once again to 2029 in late 2021 and then moved up to 2026.

Sweden does not currently use the euro as its currency and has no plans to replace the existing Swedish krona in the near future. Sweden's Treaty of Accession of 1994 made it subject to the Treaty of Maastricht, which obliges states to join the eurozone once they meet the necessary conditions. Sweden maintains that joining the European Exchange Rate Mechanism II, participation in which for at least two years is a requirement for euro adoption, is voluntary, and has chosen to remain outside pending public approval by a referendum, thereby intentionally avoiding the fulfilment of the adoption requirements.

The United Kingdom did not seek to adopt the euro as its official currency for the duration of its membership of the European Union (EU), and secured an opt-out at the euro's creation via the Maastricht Treaty in 1992, wherein the Bank of England would only be a member of the European System of Central Banks.

Denmark uses the krone as its currency and does not use the euro, having negotiated the right to opt out from participation under the Maastricht Treaty of 1992. In 2000, the government held a referendum on introducing the euro, which was defeated with 53.2% voting no and 46.8% voting yes. The Danish krone is part of the ERM II mechanism, so its exchange rate is tied to within 2.25% of the euro.

The enlargement of the eurozone is an ongoing process within the European Union (EU). All member states of the European Union, except Denmark which negotiated an opt-out from the provisions, are obliged to adopt the euro as their sole currency once they meet the criteria, which include: complying with the debt and deficit criteria outlined by the Stability and Growth Pact, keeping inflation and long-term governmental interest rates below certain reference values, stabilising their currency's exchange rate versus the euro by participating in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism, and ensuring that their national laws comply with the ECB statute, ESCB statute and articles 130+131 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. The obligation for EU member states to adopt the euro was first outlined by article 109.1j of the Maastricht Treaty of 1992, which became binding on all new member states by the terms of their treaties of accession.

Within the framework of EU economic governance, Sixpack describes a set of European legislative measures to reform the Stability and Growth Pact and introduces greater macroeconomic surveillance, in response to the European debt crisis of 2009. These measures were bundled into a "six pack" of regulations, introduced in September 2010 in two versions respectively by the European Commission and a European Council task force. In March 2011, the ECOFIN council reached a preliminary agreement for the content of the Sixpack with the commission, and negotiations for endorsement by the European Parliament then started. Ultimately it entered into force 13 December 2011, after one year of preceding negotiations. The six regulations aim at strengthening the procedures to reduce public deficits and address macroeconomic imbalances.

Croatia adopted the euro as its currency on 1 January 2023, becoming the 20th member state of the eurozone. A fixed conversion rate was set at 1 € = 7.5345 kn.

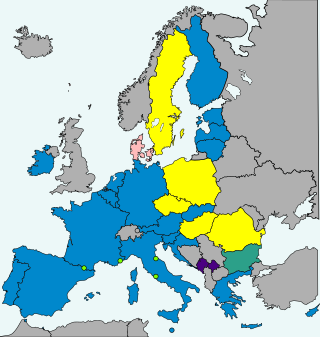

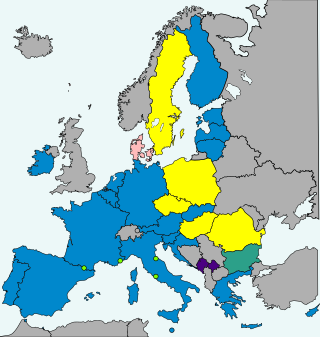

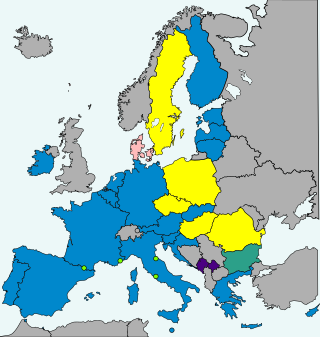

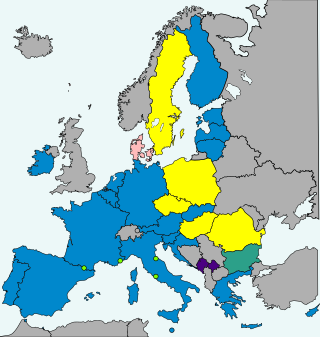

![Eurozone participation

European Union member states

.mw-parser-output .legend{page-break-inside:avoid;break-inside:avoid-column}.mw-parser-output .legend-color{display:inline-block;min-width:1.25em;height:1.25em;line-height:1.25;margin:1px 0;text-align:center;border:1px solid black;background-color:transparent;color:black}.mw-parser-output .legend-text{}

20 in the eurozone

1 in ERM II, without an opt-out (Bulgaria)

1 in ERM II, with an opt-out (Denmark)

5 not in ERM II, but obliged to join the eurozone on meeting the convergence criteria (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden)

Non-EU member states

4 using the euro with a monetary agreement (Andorra, Monaco, San Marino, and Vatican City)

2 using the euro unilaterally (Kosovo and Montenegro)

.mw-parser-output .hlist dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul{margin:0;padding:0}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt,.mw-parser-output .hlist li{margin:0;display:inline}.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline,.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline ul,.mw-parser-output .hlist dl dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist dl ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist dl ul,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol ul,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul ul{display:inline}.mw-parser-output .hlist .mw-empty-li{display:none}.mw-parser-output .hlist dt::after{content:": "}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li::after{content:" * ";font-weight:bold}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li:last-child::after{content:none}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dd:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dt:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dd:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dt:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dd:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dt:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li li:first-child::before{content:" (";font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd li:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt li:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li li:last-child::after{content:")";font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .hlist ol{counter-reset:listitem}.mw-parser-output .hlist ol>li{counter-increment:listitem}.mw-parser-output .hlist ol>li::before{content:" "counter(listitem)"\a0 "}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd ol>li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt ol>li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li ol>li:first-child::before{content:" ("counter(listitem)"\a0 "}

.mw-parser-output .navbar{display:inline;font-size:88%;font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .navbar-collapse{float:left;text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .navbar-boxtext{word-spacing:0}.mw-parser-output .navbar ul{display:inline-block;white-space:nowrap;line-height:inherit}.mw-parser-output .navbar-brackets::before{margin-right:-0.125em;content:"[ "}.mw-parser-output .navbar-brackets::after{margin-left:-0.125em;content:" ]"}.mw-parser-output .navbar li{word-spacing:-0.125em}.mw-parser-output .navbar a>span,.mw-parser-output .navbar a>abbr{text-decoration:inherit}.mw-parser-output .navbar-mini abbr{font-variant:small-caps;border-bottom:none;text-decoration:none;cursor:inherit}.mw-parser-output .navbar-ct-full{font-size:114%;margin:0 7em}.mw-parser-output .navbar-ct-mini{font-size:114%;margin:0 4em}

v

t

e Eurozone participation.svg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c6/Eurozone_participation.svg/301px-Eurozone_participation.svg.png)