Pattern welding is an practice in sword and knife making by forming a blade of several metal pieces of differing composition that are forge-welded together and twisted and manipulated to form a pattern. Often mistakenly called Damascus steel, blades forged in this manner often display bands of slightly different patterning along their entire length. These bands can be highlighted for cosmetic purposes by proper polishing or acid etching. Pattern welding was an outgrowth of laminated or piled steel, a similar technique used to combine steels of different carbon contents, providing a desired mix of hardness and toughness. Although modern steelmaking processes negate the need to blend different steels, pattern welded steel is still used by custom knifemakers for the cosmetic effects it produces.

A polearm or pole weapon is a close combat weapon in which the main fighting part of the weapon is fitted to the end of a long shaft, typically of wood, extending the user's effective range and striking power. Polearms are predominantly melee weapons, with a subclass of spear-like designs fit for thrusting and/or throwing. Because many polearms were adapted from agricultural implements or other fairly abundant tools, and contained relatively little metal, they were cheap to make and readily available. When belligerents in warfare had a poorer class who could not pay for dedicated military weapons, they would often appropriate tools as cheap weapons. The cost of training was comparatively low, since these conscripted farmers had spent most of their lives using these "weapons" in the fields. This made polearms the favoured weapon of peasant levies and peasant rebellions the world over.

A longsword is a type of European sword characterized as having a cruciform hilt with a grip for primarily two-handed use, a straight double-edged blade of around 80 to 110 cm, and weighing approximately 2 to 3 kg.

A flame-bladed sword or wave-bladed sword has a characteristically undulating style of blade. The wave in the blade is often considered to contribute a flame-like quality to the appearance of a sword. The dents on the blade can appear parallel or in a zig-zag manner. The two most common flame-bladed swords are rapiers or Zweihänders. A flame-bladed sword was not exclusive to a certain country or region. The style of blade can be found on swords from modern-day Germany, France, Spain, and Switzerland.

The Dane axe or long axe is a type of European early medieval period two-handed battle axe with a very long shaft, around 0.9–1.2 metres at the low end to 1.5–1.7 metres or more at the long end. Sometimes called a broadaxe, the blade was broad and thin, intended to give a long powerful cut when swung, effective against cavalry, shields and unarmored opponents.

Knowledge about military technology of the Viking Age is based on relatively sparse archaeological finds, pictorial representations, and to some extent on the accounts in the Norse sagas and laws recorded in the 12th–14th centuries.

The Viking Age sword or Carolingian sword is the type of sword prevalent in Western and Northern Europe during the Early Middle Ages.

Ronald Ewart Oakeshott was a British illustrator, collector, and amateur historian who wrote prodigiously on medieval arms and armour. He was a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, a Founder Member of the Arms and Armour Society, and the Founder of the Oakeshott Institute. He created a classification system of the medieval sword, the Oakeshott typology, a systematic organization of medieval weaponry.

The Oakeshott typology is a way to define and catalogue the medieval sword based on physical form. It categorises the swords of the European Middle Ages into 13 main types, labelled X through XXII. The historian and illustrator Ewart Oakeshott introduced it in his 1960 treatise The Archaeology of Weapons: Arms and Armour from Prehistory to the Age of Chivalry.

A sword's crossguard or cross-guard is a bar between the blade and hilt, essentially perpendicular to them, intended to protect the wielder's hand and fingers from opponents' weapons as well as from his or her own blade. Each of the individual bars on either side is known as a quillon or quillion.

Chape has had various meanings in English, but the predominant one is a protective fitting at the bottom of a scabbard or sheath for a sword or dagger. Historic blade weapons often had leather scabbards with metal fittings at either end, sometimes decorated. These are generally either in some sort of U shape, protecting the edges only, or a pocket shape covering the sides of the scabbard as well. The reinforced end of a single-piece metal scabbard can also be called the chape.

The period of Anglo-Saxon warfare spans the 5th century AD to the 11th in Anglo-Saxon England. Its technology and tactics resemble those of other European cultural areas of the Early Medieval Period, although the Anglo-Saxons, unlike the Continental Germanic tribes such as the Franks and the Goths, do not appear to have regularly fought on horseback.

The Migration Period sword was a type of sword popular during the Migration Period and the Merovingian period of European history, particularly among the Germanic peoples. It later gave rise to the Carolingian or Viking sword type of the 8th to 11th centuries AD.

The Cawood sword is a medieval sword discovered in the River Ouse near Cawood in North Yorkshire in the late 19th century. The blade is of Oakeshott type XII and has inscriptions on both sides. It most likely dates to the early 12th century.

An atgeir, sometimes called a "mail-piercer" or "hewing-spear", was a type of polearm in use in Viking Age Scandinavia and Norse colonies in the British Isles and Iceland. The word is related to the Old Norse geirr, meaning spear. It is usually translated in English as "halberd", but most likely more closely resembled a bill or glaive during the Viking age. Another view is that the term had no association with a specific weapon until it is used as an anachronism in saga literature to lend weight to accounts of special weapons. Later the word was used for typical European halberds, and even later multipurpose staves with spearheads were called atgeirsstafir.

The Seax of Beagnoth is a 10th-century Anglo-Saxon seax. It was found in the inland estuary of the Thames in 1857, and is now at the British Museum in London. It is a prestige weapon, decorated with elaborate patterns of inlaid copper, brass and silver wire. On one side of the blade is the only known complete inscription of the twenty-eight letter Anglo-Saxon runic alphabet, as well as the name "Beagnoth" in runic letters. It is thought that the runic alphabet had a magical function, and that the name Beagnoth is that of either the owner of the weapon or the smith who forged it. Although many Anglo-Saxon and Viking swords and knives have inscriptions in the Latin alphabet on their blades, or have runic inscriptions on the hilt or scabbard, the Seax of Beagnoth is one of only a handful of finds with a runic inscription on its blade.

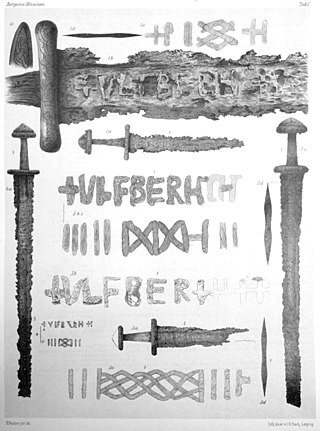

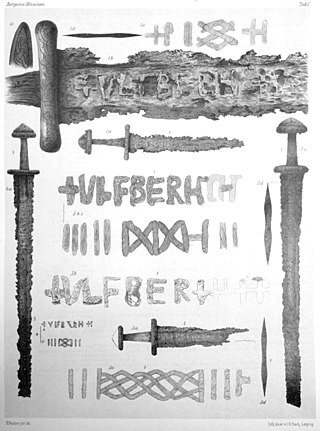

The Ulfberht swords are a group of about 170 medieval swords found primarily in Northern Europe, dated to the 9th to 11th centuries, with blades inlaid with the inscription +VLFBERH+T or +VLFBERHT+. The word "Ulfberht" is a Frankish personal name, possibly indicating the origin of the blades.

The basket-hilted sword is a sword type of the early modern era characterised by a basket-shaped guard that protects the hand. The basket hilt is a development of the quillons added to swords' crossguards since the Late Middle Ages. This variety of sword is also sometimes referred to as the broadsword, though this term may also be applied loosely and imprecisely to other swords.

In the European High Middle Ages, the typical sword was a straight, double-edged weapon with a single-handed, cruciform hilt and a blade length of about 70 to 80 centimetres. This type is frequently depicted in period artwork, and numerous examples have been preserved archaeologically.

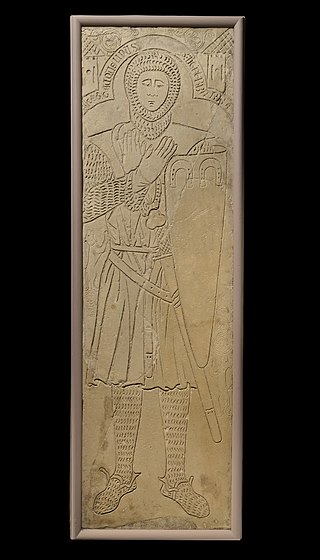

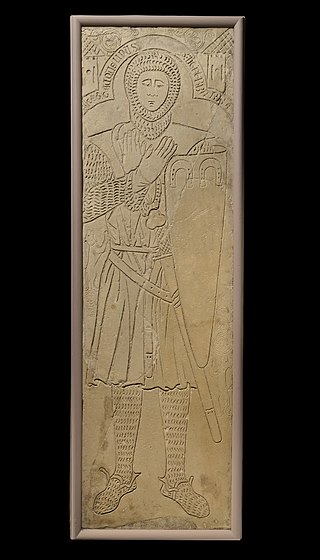

The Tomb Effigy of Jacquelin de Ferrière is usually on display in the Medieval Art Gallery of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The effigy is of the French knight, Sir Jacquelin de Ferrière, who was from Montargis, near Sens in northern France. The effigy is dated between 1275-1300 CE. It is 73+3⁄4 in (187 cm) long, 24+5⁄8 in (63 cm) wide, and 5 inches (13 cm) deep, and carved into a flat limestone slab, which now has a wooden frame. Effigies were often commissioned by the nobles or their families, as a means of remembrance. They would normally be found covering the sarcophagi of the knight, or installed in or near a church that the family were patrons of. Although the inscription on this effigy is not clear, most effigies contained similar inscriptions that would include the name and title, dates of birth and death–or approximates, a link between the date of death and a notable holy figure or day, and petitions of prayer that would offer pardons to those that prayed for the depicted soul–largely an attempt to create a tangible link between the nobility and divinity.