John P. Walters | |

|---|---|

| |

| Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy | |

| In office December 7, 2001 –January 20, 2009 | |

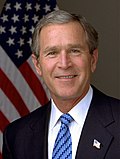

| President | George W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Barry McCaffrey |

| Succeeded by | Gil Kerlikowske |

| Acting January 20,1993 –July 19,1993 | |

| President | Bill Clinton |

| Preceded by | Bob Martinez |

| Succeeded by | Lee Brown |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 8,1952 |

| Political party | Republican |

| Education | |

John P. Walters (born February 8, 1952) is the president and chief executive officer of Hudson Institute; he was appointed in January 2021. He joined Hudson in 2009 as the executive vice president and most recently was the chief operating officer. [1] Previously, Walters was Director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) in the George W. Bush administration. He held that position from February 5, 2001, to January 20, 2009. As the U.S. "Drug Czar", Walters coordinated all aspects of federal anti-drug policies and spending. As drug czar, he was a staunch opponent of drug decriminalization, legalization, and medical marijuana. [2] [3]