Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan ibn al-Hakam was the fifth Umayyad caliph, ruling from April 685 until his death in October 705. A member of the first generation of born Muslims, his early life in Medina was occupied with pious pursuits. He held administrative and military posts under Caliph Mu'awiya I, founder of the Umayyad Caliphate, and his own father, Caliph Marwan I. By the time of Abd al-Malik's accession, Umayyad authority had collapsed across the Caliphate as a result of the Second Fitna and had been reconstituted in Syria and Egypt during his father's reign.

Mu'awiya I was the founder and first caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate, ruling from 661 until his death. He became caliph less than thirty years after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and immediately after the four Rashidun ('rightly-guided') caliphs. Unlike his predecessors, who had been close, early companions of Muhammad, Mu'awiya was a relatively late follower of Muhammad.

Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan was the seventh Umayyad caliph, ruling from 715 until his death. He was the son of Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (r. 685–705) and Wallada bint al-Abbas. He began his career as governor of Palestine, while his father Abd al-Malik and brother al-Walid I reigned as caliphs. There, the theologian Raja ibn Haywa al-Kindi mentored him, and he forged close ties with Yazid ibn al-Muhallab, a major opponent of al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, al-Walid's powerful viceroy of Iraq and the eastern Caliphate. Sulayman resented al-Hajjaj's influence over his brother. As governor, Sulayman founded the city of Ramla and built the White Mosque in it. The new city superseded Lydda as the district capital of Palestine. Lydda was at least partly destroyed and its inhabitants may have been forcibly relocated to Ramla, which developed into an economic hub, became home to many Muslim scholars, and remained the commercial and administrative center of Palestine until the 11th century.

Bilad al-Sham, often referred to as Islamic Syria or simply Syria in English-language sources, was a province of the Rashidun, Umayyad, Abbasid, and Fatimid caliphates. It roughly corresponded with the Byzantine Diocese of the East, conquered by the Muslims in 634–647. Under the Umayyads (661–750), Bilad al-Sham was the metropolitan province of the Caliphate and different localities throughout the province served as the seats of the Umayyad caliphs and princes.

The Judham was a large Arab tribe that inhabited the southern Levant and northwestern Arabia during the late antique and early Islamic eras. Under the Byzantine Empire, the tribe was nominally Christian and fought against the Muslim armies between 629 and 636, until the Byzantines and their Arab allies were defeated at the Battle of Yarmouk. Afterward, the Judham converted to Islam and became the largest tribal faction of Jund Filastin.

Jund al-Urdunn was one of the five districts of Bilad al-Sham during the early Islamic period. It was established under the Rashidun and its capital was Tiberias throughout its rule by the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphates. It encompassed southern Mount Lebanon, the Galilee, the southern Hauran, the Golan Heights, and most of the eastern Jordan Valley.

Jund Ḥimṣ was one of the military districts of the caliphal province of Syria.

Jund Dimashq was the largest of the sub-provinces, into which Syria was divided under the Umayyad and Abbasid dynasties. It was named after its capital and largest city, Damascus ("Dimashq"), which in the Umayyad period was also the capital of the Caliphate.

The Quda'a were a confederation of Arab tribes, including the powerful Kalb and Tanukh, mainly concentrated throughout Syria and northwestern Arabia, from at least the 4th century CE, during Byzantine rule, through the 12th century, during the early Islamic era. Under the first caliphs of the Syria-based Umayyad Caliphate (661–750), the Quda'a occupied a privileged position in the administration and military. During the Second Muslim Civil War (683–692) they allied with South Arabian and other tribes in Syria as the Yaman faction in opposition to their rivals, the Qays confederation, in what became a rivalry for power and influence which continued well after the Umayyad era. In forging this alliance, the Quda'a's leaders genealogically realigned their descent to the South Arabian Himyar, discarding their north Arabian ancestor, Ma'add, a move which elicited centuries-long debate and controversy among early Islamic scholars.

Kinana is an Arab tribe based around Mecca in the Tihama coastal area and the Hejaz mountains. The Quraysh of Mecca, the tribe of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, was an offshoot of the Kinana. A number of modern-day tribes throughout the Arab world trace their lineage to the tribe.

The Umayyad dynasty or Umayyads was an Arab clan within the Quraysh tribe who were the ruling family of the Caliphate between 661 and 750 and later of al-Andalus between 756 and 1031. In the pre-Islamic period, they were a prominent clan of the Meccan tribe of Quraysh, descended from Umayya ibn Abd Shams. Despite staunch opposition to the Islamic prophet Muhammad, the Umayyads embraced Islam before the former's death in 632. Uthman, an early companion of Muhammad from the Umayyad clan, was the third Rashidun caliph, ruling in 644–656, while other members held various governorships. One of these governors, Mu'awiya I of Syria, opposed Caliph Ali in the First Muslim Civil War (656–661) and afterward founded the Umayyad Caliphate with its capital in Damascus. This marked the beginning of the Umayyad dynasty, the first hereditary dynasty in the history of Islam, and the only one to rule over the entire Islamic world of its time.

Abu al-Hudhayl Zufar ibn al-Harith al-Kilabi was a Muslim commander, a chieftain of the Arabian tribe of Banu Amir, and the preeminent leader of the Qays tribal–political faction in the late 7th century. During the First Muslim Civil War he commanded his tribe in A'isha's army against Caliph Ali's forces at the Battle of the Camel near Basra in 656. The following year, he relocated from Iraq to the Jazira and fought under Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan, future founder of the Umayyad Caliphate, against Ali at the Battle of Siffin. During the Second Muslim Civil War he served Mu'awiya's son, Caliph Yazid I, leading the troops of Jund Qinnasrin against anti-Umayyad rebels in the 683 Battle of al-Harra.

Hassan ibn Malik ibn Bahdal al-Kalbi (Arabic: حسان بن مالك بن بحدل الكلبي, romanized: Ḥassān ibn Mālik ibn Baḥdal al-Kalbī, commonly known as Ibn Bahdal, was the Umayyad governor of Palestine and Jordan during the reigns of Mu'awiya I and Yazid I, a senior figure in the caliph's court, and a chieftain of the Banu Kalb tribe. He owed his position both to his leadership of the powerful Kalb, a major source of troops, and his kinship with the Umayyads through his aunt Maysun bint Bahdal, the wife of Mu'awiya and mother of Yazid. Following Yazid's death, Ibn Bahdal served as the guardian of his son and successor, Mu'awiya II, until the latter's premature death in 684. Amid the political instability and rebellions that ensued in the caliphate, Ibn Bahdal attempted to secure the succession Mu'awiya II's brother Khalid, but ultimately threw his support behind Marwan I, who hailed from a different branch of the Umayyads. Ibn Bahdal and his tribal allies defeated Marwan's opponents at the Battle of Marj Rahit and secured for themselves the most prominent roles in the Umayyad administration and military.

Abū Zurʿa Rawḥ ibn Zinbāʿ al-Judhāmī was the Umayyad governor of Palestine, one of the main advisers of Caliph Abd al-Malik and the chieftain of the Judham tribe.

Sa'id ibn Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, also known as Saʿīd al-Khayr, was an Umayyad prince and governor.

Natil ibn Qays ibn Zayd al-Judhami was the chieftain of the Banu Judham tribe and a prominent tribal leader in Palestine during the reigns of caliphs Mu'awiya I and Yazid I. In 684, he revolted against the Umayyads, took control of Palestine and gave his allegiance to Caliph Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr. He joined the latter in Mecca after pro-Zubayrid forces were routed at the Battle of Marj Rahit. He may have renewed his rebellion in Palestine in 685/86 and was slain during the hostilities.

The history of Jerusalem during the Early Muslim period covers the period between the capture of the city from the Byzantines by the Arab Muslim armies of the nascent Caliphate in 637–638 CE, and its conquest by the European Catholic armies of the First Crusade in 1099. Throughout this period, Jerusalem remained a largely Christian city with smaller Muslim and Jewish communities. It was successively part of several Muslim states, beginning with the Rashidun caliphs of Medina, the Umayyads of Syria, the Abbasids of Baghdad and their nominal Turkish vassals in Egypt, and the Fatimid caliphs of Cairo, who struggled over it with the Turkic Seljuks and different other regional powers, only to finally lose it to the Crusaders.

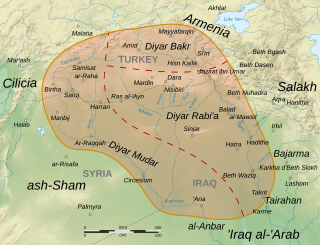

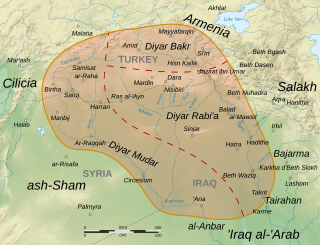

Al-Jazira, also known as Jazirat Aqur or Iqlim Aqur, was a province of the Rashidun, Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates, spanning at minimum most of Upper Mesopotamia, divided between the districts of Diyar Bakr, Diyar Rabi'a and Diyar Mudar, and at times including Mosul, Arminiya and Adharbayjan as sub-provinces. Following its conquest by the Muslim Arabs in 639/40, it became an administrative unit attached to the larger district of Jund Hims. It was separated from Hims during the reigns of caliphs Mu'awiya I or Yazid I and came under the jurisdiction of Jund Qinnasrin. It was made its own province in 692 by Caliph Abd al-Malik. After 702, it frequently came to span the key districts of Arminiya and Adharbayjan along the Caliphate's northern frontier, making it a super-province. The predominance of Arabs from the Qays/Mudar and Rabi'a groups made it a major recruitment pool of tribesmen for the Umayyad armies and the troops of the Jazira played a key military role under the Umayyad caliphs in the 8th century, peaking under the last Umayyad caliph, Marwan II, until the toppling of the Umayyads by the Abbasids in 750.

Alqama ibn Mujazziz al-Mudliji al-Kinani was an early Muslim commander under the Islamic prophet Muhammad and the caliphs Abu Bakr and Umar. He was a leading commander and governor of Jund Filastin under Abu Bakr, Umar, and possibly for a relatively short period under Uthman.

Rumahis ibn Abd al-Aziz al-Kinani was the governor of Jund Filastin under the Umayyad caliph Marwan II and the governor of Algeciras under the Umayyad Emir of Cordoba, Abd al-Rahman I.