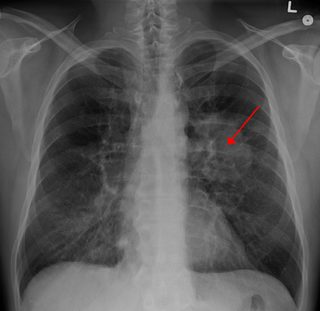

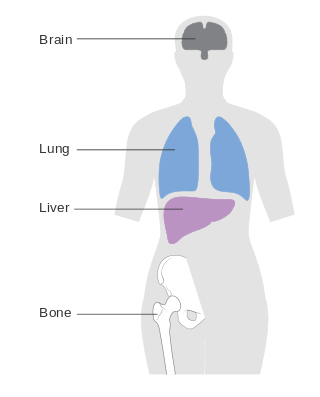

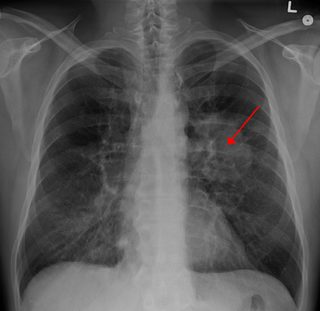

Lung cancer, also known as lung carcinoma, is a malignant tumor that begins in the lung. Lung cancer is caused by genetic damage to the DNA of cells in the airways, often caused by cigarette smoking or inhaling damaging chemicals. Damaged airway cells gain the ability to multiply unchecked, causing the growth of a tumor. Without treatment, tumors spread throughout the lung, damaging lung function. Eventually lung tumors metastasize, spreading to other parts of the body.

Radiation therapy or radiotherapy is a treatment using ionizing radiation, generally provided as part of cancer therapy to either kill or control the growth of malignant cells. It is normally delivered by a linear particle accelerator. Radiation therapy may be curative in a number of types of cancer if they are localized to one area of the body, and have not spread to other parts. It may also be used as part of adjuvant therapy, to prevent tumor recurrence after surgery to remove a primary malignant tumor. Radiation therapy is synergistic with chemotherapy, and has been used before, during, and after chemotherapy in susceptible cancers. The subspecialty of oncology concerned with radiotherapy is called radiation oncology. A physician who practices in this subspecialty is a radiation oncologist.

Brachytherapy is a form of radiation therapy where a sealed radiation source is placed inside or next to the area requiring treatment. Brachy is Greek for short. Brachytherapy is commonly used as an effective treatment for cervical, prostate, breast, esophageal and skin cancer and can also be used to treat tumours in many other body sites. Treatment results have demonstrated that the cancer-cure rates of brachytherapy are either comparable to surgery and external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) or are improved when used in combination with these techniques. Brachytherapy can be used alone or in combination with other therapies such as surgery, EBRT and chemotherapy.

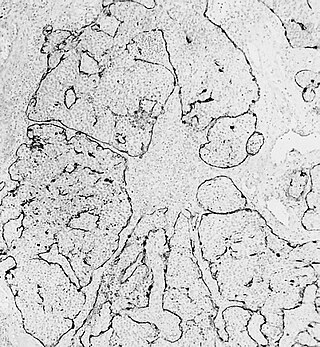

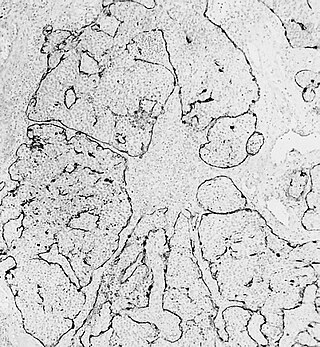

Small-cell carcinoma is a type of highly malignant cancer that most commonly arises within the lung, although it can occasionally arise in other body sites, such as the cervix, prostate, and gastrointestinal tract. Compared to non-small cell carcinoma, small cell carcinoma is more aggressive, with a shorter doubling time, higher growth fraction, and earlier development of metastases.

In medicine, proton therapy, or proton radiotherapy, is a type of particle therapy that uses a beam of protons to irradiate diseased tissue, most often to treat cancer. The chief advantage of proton therapy over other types of external beam radiotherapy is that the dose of protons is deposited over a narrow range of depth; hence in minimal entry, exit, or scattered radiation dose to healthy nearby tissues.

Invasive carcinoma of no special type, invasive breast carcinoma of no special type (IBC-NST), invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC) or invasive ductal carcinoma, not otherwise specified (NOS) is a disease. For international audiences this article will use "invasive carcinoma NST" because it is the preferred term of the World Health Organization (WHO).

Adjuvant therapy, also known as adjunct therapy, adjuvant care, or augmentation therapy, is a therapy that is given in addition to the primary or initial therapy to maximize its effectiveness. The surgeries and complex treatment regimens used in cancer therapy have led the term to be used mainly to describe adjuvant cancer treatments. An example of such adjuvant therapy is the additional treatment usually given after surgery where all detectable disease has been removed, but where there remains a statistical risk of relapse due to the presence of undetected disease. If known disease is left behind following surgery, then further treatment is not technically adjuvant.

Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), or non-small-cell lung carcinoma, is any type of epithelial lung cancer other than small-cell lung cancer (SCLC). NSCLC accounts for about 85% of all lung cancers. As a class, NSCLCs are relatively insensitive to chemotherapy, compared to small-cell carcinoma. When possible, they are primarily treated by surgical resection with curative intent, although chemotherapy has been used increasingly both preoperatively and postoperatively.

Mitumomab (BEC-2) is a mouse anti-BEC-2 monoclonal antibody investigated for the treatment of small cell lung carcinoma in combination with BCG vaccination. Mitumomab attacks tumour cells, while the vaccine is thought to activate the immune system. It was developed by ImClone and Merck.

Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) of the lung —previously included in the category of "bronchioloalveolar carcinoma" (BAC)—is a subtype of lung adenocarcinoma. It tends to arise in the distal bronchioles or alveoli and is defined by a non-invasive growth pattern. This small solitary tumor exhibits pure alveolar distribution and lacks any invasion of the surrounding normal lung. If completely removed by surgery, the prognosis is excellent with up to 100% 5-year survival.

Esthesioneuroblastoma is a rare cancer of the nasal cavity. Arising from the upper nasal tract, esthesioneuroblastoma is believed to originate from sensory neuroepithelial cells, also known as neuroectodermal olfactory cells.

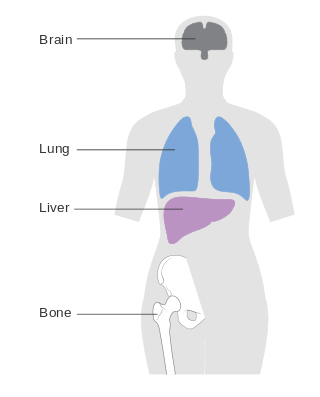

Metastatic breast cancer, also referred to as metastases, advanced breast cancer, secondary tumors, secondaries or stage IV breast cancer, is a stage of breast cancer where the breast cancer cells have spread to distant sites beyond the axillary lymph nodes. There is no cure for metastatic breast cancer; there is no stage after IV.

Human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal cancer, is a cancer of the throat caused by the human papillomavirus type 16 virus (HPV16). In the past, cancer of the oropharynx (throat) was associated with the use of alcohol or tobacco or both, but the majority of cases are now associated with the HPV virus, acquired by having oral contact with the genitals of a person who has a genital HPV infection. Risk factors include having a large number of sexual partners, a history of oral-genital sex or anal–oral sex, having a female partner with a history of either an abnormal Pap smear or cervical dysplasia, having chronic periodontitis, and, among men, younger age at first intercourse and a history of genital warts. HPV-positive OPC is considered a separate disease from HPV-negative oropharyngeal cancer.

A brain metastasis is a cancer that has metastasized (spread) to the brain from another location in the body and is therefore considered a secondary brain tumor. The metastasis typically shares a cancer cell type with the original site of the cancer. Metastasis is the most common cause of brain cancer, as primary tumors that originate in the brain are less common. The most common sites of primary cancer which metastasize to the brain are lung, breast, colon, kidney, and skin cancer. Brain metastases can occur months or even years after the original or primary cancer is treated. Brain metastases have a poor prognosis for cure, but modern treatments allow patients to live months and sometimes years after the diagnosis.

Combined small cell lung carcinoma is a form of multiphasic lung cancer that is diagnosed by a pathologist when a malignant tumor, arising from transformed cells originating in lung tissue, contains a component of;small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC), admixed with one components of any histological variant of non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) in any relative proportion.

Treatment of lung cancer refers to the use of medical therapies, such as surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, percutaneous ablation, and palliative care, alone or in combination, in an attempt to cure or lessen the adverse impact of malignant neoplasms originating in lung tissue.

Targeted therapy of lung cancer refers to using agents specifically designed to selectively target molecular pathways responsible for, or that substantially drive, the malignant phenotype of lung cancer cells, and as a consequence of this (relative) selectivity, cause fewer toxic effects on normal cells.

Adenocarcinoma of the lung is the most common type of lung cancer, and like other forms of lung cancer, it is characterized by distinct cellular and molecular features. It is classified as one of several non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC), to distinguish it from small cell lung cancer which has a different behavior and prognosis. Lung adenocarcinoma is further classified into several subtypes and variants. The signs and symptoms of this specific type of lung cancer are similar to other forms of lung cancer, and patients most commonly complain of persistent cough and shortness of breath.

Prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) is a technique used to combat the occurrence of metastasis to the brain in highly aggressive cancers that commonly metastasize to brain, most notably small-cell lung cancer. Radiation therapy is commonly used to treat known tumor occurrence in the brain, either with highly precise stereotactic radiation or therapeutic cranial irradiation. By contrast, PCI is intended as preemptive treatment in patients with no known current intracranial tumor, but with high likelihood for harboring occult microscopic disease and eventual occurrence. For small-cell lung cancer with limited and select cases of extensive disease, PCI has shown to reduce recurrence of brain metastases and improve overall survival in complete remission.

Joaquín Gómez Mira is a scientist and physician specialized in radiation oncology. Born and raised in Spain, he completed his studies and developed his career in the United States, where he moved in 1967. He is a member of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and a Fellow and appointed councilor of the American College of Radiology. His work, achievements and lectures in the field of radiation oncology are held in high regard.