This article needs additional citations for verification .(October 2012) |

The Middle Angles were an important ethnic or cultural group within the larger kingdom of Mercia in England in the Anglo-Saxon period.

This article needs additional citations for verification .(October 2012) |

The Middle Angles were an important ethnic or cultural group within the larger kingdom of Mercia in England in the Anglo-Saxon period.

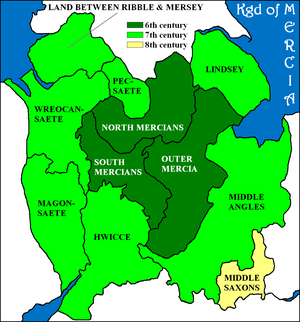

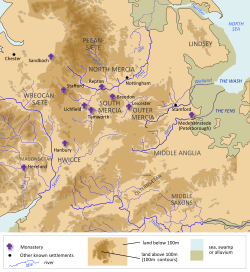

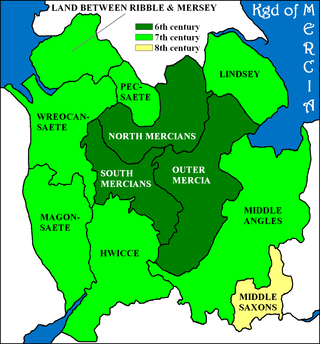

It is likely that Angles broke into the Midlands from East Anglia and the Wash early in the 6th century. Those who established their control first came to be called Middil Engli (Middle Angles). Their territory was centred in modern Leicestershire and East Staffordshire, but probably extended as far as the Cambridgeshire uplands and the Chilterns. This gave them a strategically important place within both Mercia and England as a whole, dominating both the great land routes of Watling Street and Fosse Way, and the major river route of the River Trent, together with its tributaries, the Tame and Soar.

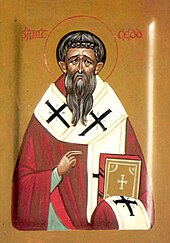

The Middle Angles were incorporated into the wider kingdom of Mercia, apparently well before the reign of Penda (c.626–655), who evidently felt safe enough to locate his base in their territory. He placed his eldest son, Peada, in charge of the Middle Angles as sub-king. [1] Bede specifies the Middle Angles as the target of a four-man Christian mission accepted by Peada, who converted to Christianity, partly in order to wed Alchflaed, the daughter of King Oswiu of Northumbria. [2] This mission arrived in 653 and included St Cedd. [1] Peada's conversion and acceptance of baptism in Northumbria possibly indicates a continuing sense of disunity or local particularism within Mercia. It is unlikely that Peada could have pursued so different a course from his father, at the strategic and political centre of the Mercian kingdom, without local support among the Middle Angles.

Following the defeat and death of Penda (655), and the murder of Peada himself (656) at the instigation of his Northumbrian wife, Oswiu was able to dominate Mercia. He appointed one of the missionary priests, the Irish Diuma, bishop of the Middle Angles and the Mercians. [3] Bede makes much of the fact that a shortage of priests compelled the appointment of one bishop to two peoples. This seems to indicate that the Middle Angles, while a central part of the Mercian kingdom, were clearly distinguished from the Mercians proper, a designation that seems to have been reserved for people settled further North and West. [4] Diuma apparently died among the Middle Angles after a short but successful mission. His successor, Ceollach, another Irish missionary, returned home after a short time, for reasons that Bede does not specify. He was followed in turn by Trumhere and Jaruman.

Wulfhere, another son of Penda, continued to base his rule over Mercia among the Middle Angles, with the royal centre at Tamworth. In 669, after the death of Jaruman, he requested that the archbishop of Canterbury send a new bishop. This was Chad, brother of Cedd. According to Bede, Chad was designated "bishop of the Mercians and Lindsey people". In this case there is no doubt that the Middle Angles are subsumed into the category of the Mercians. The ecclesiastical centre for the entire vast region was established in Middle Angle territory, for Wulfhere donated land a short distance away from Tamworth, at Lichfield, to allow Chad to establish a monastery. It seems that the distinctions between the peoples within Mercia were gradually fading and that it was possible for them all to be described as Mercians. It is less clear whether this more accurately reflects the understanding of Chad's own time, or of Bede's, in the early 8th century.

The knowledge of Middle Angles's political history is limited, the name is not used for the Tribal Hidage with smaller areas listed and identified to be part of or around the area. The ecclesiastical history is better recorded with an area comparable to the central Mercian diocese of Lichfield, the Middle Anglian territory was therefore a major ecclesiastical centre of the wider Mercian kingdom. The early ecclesiastical see was at Leicester.

The see moved to Dorchester-on-Thames with the Danelaw established under East Mercia, Leicester became one of the Five Burghs of Danelaw with Northampton as major centre of Danelaw. After Danelaw, the diocese of Lindsey merged with the See of Dorchester (with Leicester) to form the diocese of Lincoln.

Mercia was one of the three main Anglic kingdoms founded after Sub-Roman Britain was settled by Anglo-Saxons in an era called the Heptarchy. It was centred on the River Trent and its tributaries, in a region now known as the Midlands of England.

Oswiu, also known as Oswy or Oswig, was King of Bernicia from 642 and of Northumbria from 654 until his death. He is notable for his role at the Synod of Whitby in 664, which ultimately brought the church in Northumbria into conformity with the wider Catholic Church.

Æthelred was king of Mercia from 675 until 704. He was the son of Penda of Mercia and came to the throne in 675, when his brother, Wulfhere of Mercia, died from an illness. Within a year of his accession he invaded Kent, where his armies destroyed the city of Rochester. In 679 he defeated his brother-in-law, Ecgfrith of Northumbria, at the Battle of the Trent: the battle was a major setback for the Northumbrians, and effectively ended their military involvement in English affairs south of the Humber. It also permanently returned the Kingdom of Lindsey to Mercia's possession. However, Æthelred was unable to re-establish his predecessors' domination of southern Britain.

Wulfhere or Wulfar was King of Mercia from 658 until 675 AD. He was the first Christian king of all of Mercia, though it is not known when or how he converted from Anglo-Saxon paganism. His accession marked the end of Oswiu of Northumbria's overlordship of southern England, and Wulfhere extended his influence over much of that region. His campaigns against the West Saxons led to Mercian control of much of the Thames valley. He conquered the Isle of Wight and the Meon valley and gave them to King Æthelwealh of the South Saxons. He also had influence in Surrey, Essex, and Kent. He married Eormenhild, the daughter of King Eorcenberht of Kent.

Penda was a 7th-century king of Mercia, the Anglo-Saxon kingdom in what is today the Midlands. A pagan at a time when Christianity was taking hold in many of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, Penda took over the Severn Valley in 628 following the Battle of Cirencester before participating in the defeat of the powerful Northumbrian king Edwin at the Battle of Hatfield Chase in 633.

Peada, a son of Penda, was briefly King of southern Mercia after his father's death in November 655 and until his own death at the hands of his wife in the spring of the next year.

The Battle of the Winwaed was fought on 15 November 655 between King Penda of Mercia and Oswiu of Bernicia, ending in the Mercians' defeat and Penda's death. According to Bede, the battle marked the effective demise of Anglo-Saxon paganism.

Chad was a prominent 7th-century Anglo-Saxon Catholic monk who became abbot of several monasteries, Bishop of the Northumbrians and subsequently Bishop of the Mercians and Lindsey People. He was later canonised as a saint.

Anna was king of East Anglia from the early 640s until his death. He was a member of the Wuffingas family, the ruling dynasty of the East Angles, and one of the three sons of Eni who ruled the kingdom of East Anglia, succeeding some time after Ecgric was killed in battle by Penda of Mercia. Anna was praised by Bede for his devotion to Christianity and was renowned for the saintliness of his family: his son Jurmin and all his daughters – Seaxburh, Æthelthryth, Æthelburh and possibly a fourth, Wihtburh – were canonised.

Sigeberht II, nicknamed the Good (Bonus) or the Blessed (Sanctus), was King of the East Saxons, in succession to his relative Sigeberht I the Little. Although a bishopric in Essex had been created under Mellitus, the kingdom had lapsed to paganism and it was in Sigeberht's reign that a systematic (re-)conversion of the East Anglians took root. Bede's Historia Ecclesiastica, Book III, chapter 22, is virtually the sole source for his career.

Cedd was an Anglo-Saxon monk and bishop from the Kingdom of Northumbria. He was an evangelist of the Middle Angles and East Saxons in England and a significant participant in the Synod of Whitby, a meeting which resolved important differences within the Church in England. He is venerated in the Catholic Church, Anglicanism, and the Orthodox Church.

The Tribal Hidage is a list of thirty-five tribes that was compiled in Anglo-Saxon England some time between the 7th and 9th centuries. It includes a number of independent kingdoms and other smaller territories, and assigns a number of hides to each one. The list is headed by Mercia and consists almost exclusively of peoples who lived south of the Humber estuary and territories that surrounded the Mercian kingdom, some of which have never been satisfactorily identified by scholars. The value of 100,000 hides for Wessex is by far the largest: it has been suggested that this was a deliberate exaggeration.

Medeshamstede was the name of Peterborough in the Anglo-Saxon period. It was the site of a monastery founded around the middle of the 7th century, which was an important feature in the kingdom of Mercia from the outset. Little is known of its founder and first abbot, Sexwulf, though he was himself an important figure, and later became bishop of Mercia. Medeshamstede soon acquired a string of daughter churches, and was a centre for an Anglo-Saxon sculptural style.

Æthelwold, also known as Æthelwald or Æþelwald, was a 7th-century king of East Anglia, the long-lived Anglo-Saxon kingdom which today includes the English counties of Norfolk and Suffolk. He was a member of the Wuffingas dynasty, which ruled East Anglia from their regio at Rendlesham. The two Anglo-Saxon cemeteries at Sutton Hoo, the monastery at Iken, the East Anglian see at Dommoc and the emerging port of Ipswich were all in the vicinity of Rendlesham.

Diuma was the first Bishop of Mercia in the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Mercia, during the Early Middle Ages.

The Wreocensæte, sometimes anglicized as the Wrekinsets, were one of the peoples of Anglo-Saxon Britain. Their name approximates to "Wrekin-dwellers". It is also suggested that Wrexham also derived from Wreocensæte.

The Kingdom of the East Angles, informally known as the Kingdom of East Anglia, was a small independent kingdom of the Angles during the Anglo-Saxon period comprising what are now the English counties of Norfolk and Suffolk and perhaps the eastern part of the Fens, the area still known as East Anglia.

Events from the 7th century in England.

Throughout its history the Kingdom of Mercia was a battleground between conflicting religious ideologies.

Urbs Iudeu was a city, whose location is now unknown, which according to the ninth-century Historia Brittonum was besieged in 655 AD by Penda, King of Mercia, and Cadafael, King of Gwynedd.