A scale-free network is a network whose degree distribution follows a power law, at least asymptotically. That is, the fraction P(k) of nodes in the network having k connections to other nodes goes for large values of k as

Social network analysis (SNA) is the process of investigating social structures through the use of networks and graph theory. It characterizes networked structures in terms of nodes and the ties, edges, or links that connect them. Examples of social structures commonly visualized through social network analysis include social media networks, meme spread, information circulation, friendship and acquaintance networks, peer learner networks, business networks, knowledge networks, difficult working relationships, collaboration graphs, kinship, disease transmission, and sexual relationships. These networks are often visualized through sociograms in which nodes are represented as points and ties are represented as lines. These visualizations provide a means of qualitatively assessing networks by varying the visual representation of their nodes and edges to reflect attributes of interest.

The small-world experiment comprised several experiments conducted by Stanley Milgram and other researchers examining the average path length for social networks of people in the United States. The research was groundbreaking in that it suggested that human society is a small-world-type network characterized by short path-lengths. The experiments are often associated with the phrase "six degrees of separation", although Milgram did not use this term himself.

Diffusion of innovations is a theory that seeks to explain how, why, and at what rate new ideas and technology spread. The theory was popularized by Everett Rogers in his book Diffusion of Innovations, first published in 1962. Rogers argues that diffusion is the process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among the participants in a social system. The origins of the diffusion of innovations theory are varied and span multiple disciplines.

Homophily is a concept in sociology describing the tendency of individuals to associate and bond with similar others, as in the proverb "birds of a feather flock together". The presence of homophily has been discovered in a vast array of network studies: over 100 studies have observed homophily in some form or another, and they establish that similarity is associated with connection. The categories on which homophily occurs include age, gender, class, and organizational role.

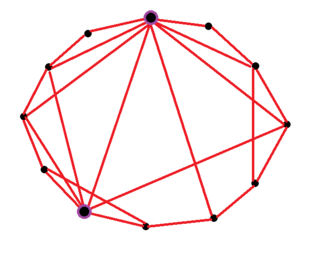

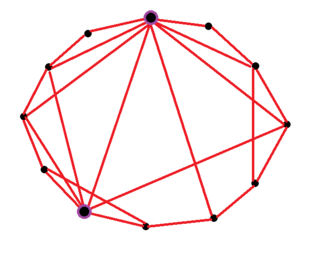

A small-world network is a graph characterized by a high clustering coefficient and low distances. On an example of social network, high clustering implies the high probability that two friends of one person are friends themselves. The low distances, on the other hand, mean that there is a short chain of social connections between any two people. Specifically, a small-world network is defined to be a network where the typical distance L between two randomly chosen nodes grows proportionally to the logarithm of the number of nodes N in the network, that is:

In the study of graphs and networks, the degree of a node in a network is the number of connections it has to other nodes and the degree distribution is the probability distribution of these degrees over the whole network.

In the study of complex networks, assortative mixing, or assortativity, is a bias in favor of connections between network nodes with similar characteristics. In the specific case of social networks, assortative mixing is also known as homophily. The rarer disassortative mixing is a bias in favor of connections between dissimilar nodes.

The Barabási–Albert (BA) model is an algorithm for generating random scale-free networks using a preferential attachment mechanism. Several natural and human-made systems, including the Internet, the World Wide Web, citation networks, and some social networks are thought to be approximately scale-free and certainly contain few nodes with unusually high degree as compared to the other nodes of the network. The BA model tries to explain the existence of such nodes in real networks. The algorithm is named for its inventors Albert-László Barabási and Réka Albert.

The Watts–Strogatz model is a random graph generation model that produces graphs with small-world properties, including short average path lengths and high clustering. It was proposed by Duncan J. Watts and Steven Strogatz in their article published in 1998 in the Nature scientific journal. The model also became known as the (Watts) beta model after Watts used to formulate it in his popular science book Six Degrees.

Assortativity, or assortative mixing, is a preference for a network's nodes to attach to others that are similar in some way. Though the specific measure of similarity may vary, network theorists often examine assortativity in terms of a node's degree. The addition of this characteristic to network models more closely approximates the behaviors of many real world networks.

In news media and social media, an echo chamber is an environment or ecosystem in which participants encounter beliefs that amplify or reinforce their preexisting beliefs by communication and repetition inside a closed system and insulated from rebuttal. An echo chamber circulates existing views without encountering opposing views, potentially resulting in confirmation bias. Echo chambers may increase social and political polarization and extremism. On social media, it is thought that echo chambers limit exposure to diverse perspectives, and favor and reinforce presupposed narratives and ideologies.

Network science is an academic field which studies complex networks such as telecommunication networks, computer networks, biological networks, cognitive and semantic networks, and social networks, considering distinct elements or actors represented by nodes and the connections between the elements or actors as links. The field draws on theories and methods including graph theory from mathematics, statistical mechanics from physics, data mining and information visualization from computer science, inferential modeling from statistics, and social structure from sociology. The United States National Research Council defines network science as "the study of network representations of physical, biological, and social phenomena leading to predictive models of these phenomena."

Heterophily, or love of the different, is the tendency of individuals to collect in diverse groups; it is the opposite of homophily. This phenomenon can be seen in relationships between individuals. As a result, it can be analyzed in the workplace to create a more efficient and innovative workplace. It has also become an area of social network analysis.

The friendship paradox is the phenomenon first observed by the sociologist Scott L. Feld in 1991 that on average, an individual's friends have more friends than that individual. It can be explained as a form of sampling bias in which people with more friends are more likely to be in one's own friend group. In other words, one is less likely to be friends with someone who has very few friends. In contradiction to this, most people believe that they have more friends than their friends have.

Evolving networks are networks that change as a function of time. They are a natural extension of network science since almost all real world networks evolve over time, either by adding or removing nodes or links over time. Often all of these processes occur simultaneously, such as in social networks where people make and lose friends over time, thereby creating and destroying edges, and some people become part of new social networks or leave their networks, changing the nodes in the network. Evolving network concepts build on established network theory and are now being introduced into studying networks in many diverse fields.

Three degrees of influence is a theory in the realm of social networks, proposed by Nicholas A. Christakis and James H. Fowler in 2007. It has since been explored by scientists in numerous disciplines using diverse statistical, mathematical, psychological, sociological, and biological approaches. Numerous large-scale in-person and online experiments have documented this phenomenon in the intervening years.

A clique, in the social sciences, is a small group of individuals who interact with one another and share similar interests rather than include others. Interacting with cliques is part of normative social development regardless of gender, ethnicity, or popularity. Although cliques are most commonly studied during adolescence and middle childhood development, they exist in all age groups. They are often bound together by shared social characteristics such as ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Examples of common or stereotypical adolescent cliques include athletes, nerds, and "outsiders".

Degree Preserving Randomization is a technique used in Network Science that aims to assess whether or not variations observed in a given graph could simply be an artifact of the graph's inherent structural properties rather than properties unique to the nodes, in an observed network.

In network theory, collective classification is the simultaneous prediction of the labels for multiple objects, where each label is predicted using information about the object's observed features, the observed features and labels of its neighbors, and the unobserved labels of its neighbors. Collective classification problems are defined in terms of networks of random variables, where the network structure determines the relationship between the random variables. Inference is performed on multiple random variables simultaneously, typically by propagating information between nodes in the network to perform approximate inference. Approaches that use collective classification can make use of relational information when performing inference. Examples of collective classification include predicting attributes of individuals in a social network, classifying webpages in the World Wide Web, and inferring the research area of a paper in a scientific publication dataset.