Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, known as Le Corbusier, was a Swiss-French architect, designer, painter, urban planner and writer, who was one of the pioneers of what is now regarded as modern architecture. He was born in Switzerland to French speaking Swiss parents, and acquired French nationality by naturalization on 19 September 1930. His career spanned five decades, in which he designed buildings in Europe, Japan, India, as well as North and South America. He considered that "the roots of modern architecture are to be found in Viollet-le-Duc".

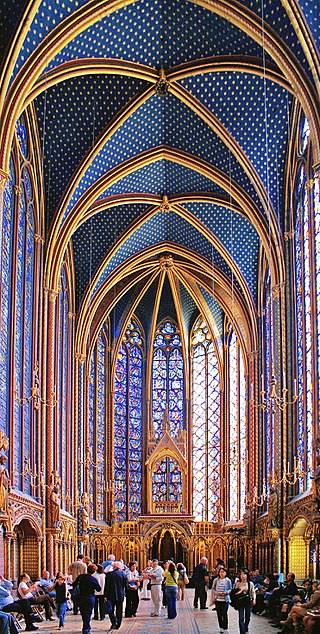

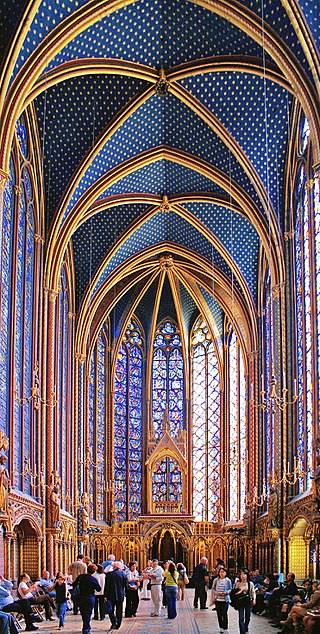

The Sainte-Chapelle is a royal chapel in the Gothic style, within the medieval Palais de la Cité, the residence of the Kings of France until the 14th century, on the Île de la Cité in the River Seine in Paris, France.

The year 1955 in architecture involved some significant architectural events and new buildings.

Strasbourg Cathedral or the Cathedral of Our Lady of Strasbourg, also known as Strasbourg Minster, is a Catholic cathedral in Strasbourg, Alsace, France. Although considerable parts of it are still in Romanesque architecture, it is widely considered to be among the finest examples of Rayonnant Gothic architecture. Architect Erwin von Steinbach is credited for major contributions from 1277 to his death in 1318, and beyond through his son Johannes von Steinbach, and his grandson Gerlach von Steinbach, who succeeded him as chief architects. The Steinbachs’ plans for the completion of the cathedral were not followed through by the chief architects who took over after them, and instead of the originally envisioned two spires, a single, octagonal tower with an elongated, octagonal crowning was built on the northern side of the west facade by master Ulrich Ensingen and his successor, Johannes Hültz. The construction of the cathedral, which had started in the year 1015 and had been relaunched in 1190, was finished in 1439.

Ronchamp is a commune in the Haute-Saône department in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté in eastern France.

Sainte Marie de La Tourette is a Dominican Order priory, located on a hillside near Lyon, France, designed by the architect Le Corbusier, the architect’s final building. The design of the building began in May 1953 and completed in 1961. The committee that decided the creation of the building considered that the primary duty of the monastery should be the spiritual awakening of the people and in particular the inhabitants of nearby areas. As a result, the monastery was constructed in Eveux-sur-Arbresle, which is just 25 km from Lyon and is accessible by train or car.

Toulouse Cathedral is a Roman Catholic church located in the city of Toulouse, France. The cathedral is a national monument, and is the seat of the Archbishop of Toulouse. It has been listed since 1862 as a monument historique by the French Ministry of Culture.

Futuna Chapel is a building in Wellington, New Zealand designed by the architect John Scott.

St. Rose of Viterbo Convent is the motherhouse of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, an American religious congregation, which is located in La Crosse, Wisconsin. The convent is dedicated to Rose of Viterbo, a 13th-century Franciscan tertiary who was a noted mystic and street preacher in Italy who died while still a teenager.

Marie-Alain Couturier, O.P., was a French Dominican friar and Catholic priest, who gained fame as a designer of stained glass windows. He was noted for his modern inspiration in the field of Sacred art.

French architecture consists of architectural styles that either originated in France or elsewhere and were developed within the territories of France.

French Gothic architecture is an architectural style which emerged in France in 1140, and was dominant until the mid-16th century. The most notable examples are the great Gothic cathedrals of France, including Notre-Dame Cathedral, Reims Cathedral, Chartres Cathedral, and Amiens Cathedral. Its main characteristics are verticality, or height, and the use of the rib vault and flying buttresses and other architectural innovations to distribute the weight of the stone structures to supports on the outside, allowing unprecedented height and volume. The new techniques also permitted the addition of larger windows, including enormous stained glass windows, which fill the cathedrals with light.

Évry Cathedral is a Roman Catholic church located in the new town of Évry, Essonne, France. The cathedral was designed by Swiss architect Mario Botta. It opened in 1995 and was consecrated and dedicated to Saint Corbinian in 1996. It is the only cathedral begun and completed in France in the 20th century.

The Musée de l'Œuvre Notre-Dame is the city of Strasbourg's museum for Upper Rhenish fine arts and decorative arts, dating from the early Middle Ages until 1681. The museum is famous for its collection of original sculptures, glass windows, architectural fragments, as well as the building plans of Strasbourg Cathedral. It has a considerable collection of works by Peter Hemmel von Andlau, Niclas Gerhaert van Leyden, Nikolaus Hagenauer, Ivo Strigel, Konrad Witz, Hans Baldung and Sebastian Stoskopff.

The city of Paris has notable examples of architecture from the Middle Ages to the 21st century. It was the birthplace of the Gothic style, and has important monuments of the French Renaissance, Classical revival, the Flamboyant style of the reign of Napoleon III, the Belle Époque, and the Art Nouveau style. The great Exposition Universelle (1889) and 1900 added Paris landmarks, including the Eiffel Tower and Grand Palais. In the 20th century, the Art Deco style of architecture first appeared in Paris, and Paris architects also influenced the postmodern architecture of the second half of the century.

Notre-Dame-de-la-Salette is a Roman Catholic church located rue de Cronstadt in the 15th arrondissement of Paris. It is under the patronage of Our Lady of La Salette, particularly revered by the religious congregation of St. Vincent de Paul.

All Saints Church, Douglas, Isle of Man, is a 1967 Modernist Anglican church which closed in May 2017.

Notre-Dame-des-Champs is a Catholic church located at 91 Boulevard du Montparnasse, at the southern edge of the 6th arrondissement of Paris. The church is named after the Blessed Virgin Mary, under the title of Our Lady of the Fields. It was completed in 1876, built using an iron framework designed by Gustave Eiffel.

Wollaston College is an Australian educational institution in Perth, Western Australia, established in 1957. It provides tertiary-level courses in theological education, professional development in theology and leadership for those working in Anglican schools and agencies, as well as forms candidates for ordination in the Anglican Church of Australia. Wollaston Theological College is a constituent college of the University of Divinity.

Notre-Dame-de-Roscudon is a Catholic church in Pont-Croix, in the French department of Finistère. Built from the 13th century through successive additions, until the second quarter of the 16th century thanks to the patronage of the lords of Pont-Croix, then their allies and descendants from the House of Rosmadec, it is an example of the patronage of the local Breton aristocracy, and bears witness to the permanence of this noble lineage throughout the three centuries of its construction.