In psychology, fantasy is a broad range of mental experiences, mediated by the faculty of imagination in the human brain, and marked by an expression of certain desires through vivid mental imagery. Fantasies are generally associated with scenarios that are impossible or unlikely to happen.

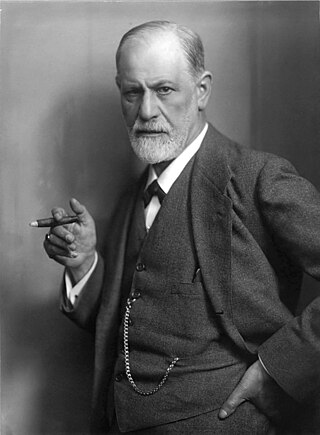

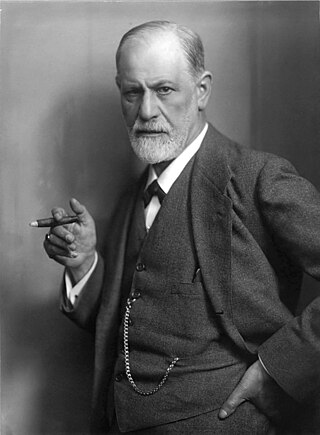

Psychoanalysis is a theory developed by Sigmund Freud. It describes the human soul as an apparatus that emerged along the path of evolution and consists mainly of three parts that complement each other in a similar way to the organelles: a set of innate needs, a consciousness that serves to satisfy them, and a memory for the retrievable storage of experiences during made. Further in, it includes insights into the effects of traumatic education and a technique for bringing repressed content back into the realm of consciousness, in particular the diagnostic interpretation of dreams. Overall, psychoanalysis represents a method for the treatment of mental disorders.

Sigmund Freud was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies seen as originating from conflicts in the psyche, through dialogue between patient and psychoanalyst, and the distinctive theory of mind and human agency derived from it.

Psychoanalytic theory is the theory of personality organization and the dynamics of personality development relating to the practice of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for treating psychopathology. First laid out by Sigmund Freud in the late 19th century, psychoanalytic theory has undergone many refinements since his work. The psychoanalytic theory came to full prominence in the last third of the twentieth century as part of the flow of critical discourse regarding psychological treatments after the 1960s, long after Freud's death in 1939. Freud had ceased his analysis of the brain and his physiological studies and shifted his focus to the study of the psyche, and on treatment using free association and the phenomena of transference. His study emphasized the recognition of childhood events that could influence the mental functioning of adults. His examination of the genetic and then the developmental aspects gave the psychoanalytic theory its characteristics.

In psychology, displacement is an unconscious defence mechanism whereby the mind substitutes either a new aim or a new object for things felt in their original form to be dangerous or unacceptable.

Transference is a phenomenon within psychotherapy in which repetitions of old feelings, attitudes, desires, or fantasies that someone displaces are subconsciously projected onto a here-and-now person. Traditionally, it had solely concerned feelings from a primary relationship during childhood.

In psychoanalysis, egosyntonic refers to the behaviors, values, and feelings that are in harmony with or acceptable to the needs and goals of the ego, or consistent with one's ideal self-image. Egodystonic is the opposite, referring to thoughts and behaviors that are conflicting or dissonant with the needs and goals of the ego, or further, in conflict with a person's ideal self-image.

Repression is a key concept of psychoanalysis, where it is understood as a defense mechanism that "ensures that what is unacceptable to the conscious mind, and would if recalled arouse anxiety, is prevented from entering into it." According to psychoanalytic theory, repression plays a major role in many mental illnesses, and in the psyche of the average person.

Wilhelm Stekel was an Austrian physician and psychologist, who became one of Sigmund Freud's earliest followers, and was once described as "Freud's most distinguished pupil". According to Ernest Jones, "Stekel may be accorded the honour, together with Freud, of having founded the first psycho-analytic society". However, a phrase used by Freud in a letter to Stekel, "the Psychological Society founded by you", suggests that the initiative was entirely Stekel's. Jones also wrote of Stekel that he was "a naturally gifted psychologist with an unusual flair for detecting repressed material". Freud and Stekel later had a falling-out, with Freud announcing in November 1912 that "Stekel is going his own way". A letter from Freud to Stekel dated January 1924 indicates that the falling out was on interpersonal rather than theoretical grounds, and that at some point Freud developed a low opinion of his former associate. He wrote: "I...contradict your often repeated assertion that you were rejected by me on account of scientific differences. This sounds quite good in public but it doesn't correspond with the truth. It was exclusively your personal qualities—usually described as character and behavior—which made collaboration with you impossible for my friends and myself." Stekel's works are translated and published in many languages.

In classical Freudian psychoanalytic theory, the death drive is the drive toward death and destruction, often expressed through behaviors such as aggression, repetition compulsion, and self-destructiveness. It was originally proposed by Sabina Spielrein in her paper "Destruction as the Cause of Coming Into Being" in 1912, which was then taken up by Sigmund Freud in 1920 in Beyond the Pleasure Principle. This concept has been translated as "opposition between the ego or death instincts and the sexual or life instincts". In Beyond thePleasure Principle, Freud used the plural "death drives" (Todestriebe) much more frequently than the singular.

In Freudian psychology and psychoanalysis, the reality principle is the ability of the mind to assess the reality of the external world, and to act upon it accordingly, as opposed to acting according to the pleasure principle. The reality principle is the governing principle of the actions taken by the ego, after its slow development from a "pleasure-ego" into a "reality-ego".

Beyond the Pleasure Principle is a 1920 essay by Sigmund Freud. It marks a major turning point in the formulation of his drive theory, where Freud had previously attributed self-preservation in human behavior to the drives of Eros and the regulation of libido, governed by the pleasure principle. Revising this as inconclusive, Freud theorized beyond the pleasure principle, newly considering the death drives which refers to the tendency towards destruction and annihilation, often expressed through behaviors such as aggression, repetition compulsion, and self-destructiveness.

Franz Gabriel Alexander was a Hungarian-American psychoanalyst and physician, who is considered one of the founders of psychosomatic medicine and psychoanalytic criminology.

In psychoanalysis, resistance is the individual's efforts to prevent repressed drives, feelings or thoughts from being integrated into conscious awareness.

Identification is a psychological process whereby the individual assimilates an aspect, property, or attribute of the other and is transformed wholly or partially by the model that other provides. It is by means of a series of identifications that the personality is constituted and specified. The roots of the concept can be found in Freud's writings. The three most prominent concepts of identification as described by Freud are: primary identification, narcissistic (secondary) identification and partial (secondary) identification.

Transference neurosis is a term that Sigmund Freud introduced in 1914 to describe a new form of the analysand's infantile neurosis that develops during the psychoanalytic process. Based on Dora's case history, Freud suggested that during therapy the creation of new symptoms stops, but new versions of the patient's fantasies and impulses are generated. He called these newer versions "transferences" and characterized them as the substitution of the analyst for a person from the patient's past. According to Freud's description: "a whole series of psychological experiences are revived not as belonging to the past, but as applying to the person of the analyst at the present moment". When transference neurosis develops, the relationship with the therapist becomes the most important one for the patient, who directs strong infantile feelings and conflicts towards the therapist, e.g. the patient may react as if the analyst is his/her father.

In psychodynamic psychotherapy, working through is seen as the process of repeating, elaborating, and amplifying interpretations. It is believed that such working through is critical towards the success of therapy.

Robert Waelder (1900–1967) was a noted Austrian psychoanalyst and member of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society. Waelder studied under Anna Freud and Hermann Nunberg. He was known for his work bringing together psychoanalysis and politics and wrote extensively on the subject.

Creative Writers and Day-Dreaming was an informal talk given in 1907 by Sigmund Freud, and subsequently published in 1908, on the relationship between unconscious phantasy and creative art.

Negative transference is the psychoanalytic term for the transference of negative and hostile feelings, rather than positive ones, onto a therapist.