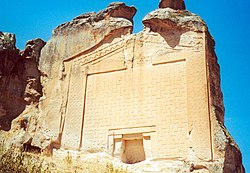

A rock-cut tomb is a burial chamber that is cut into an existing, naturally occurring rock formation, so a type of rock-cut architecture. They are usually cut into a cliff or sloping rock face, but may go downward in fairly flat ground. It was a common form of burial for the wealthy in ancient times in several parts of the world.

Contents

Important examples are found in Egypt, most notably in the town of Deir el-Medina (Seet Maat), located between the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens. [1] Other notable clusters include numerous Rock-cut tombs in ancient Israel (modern Israel and the Palestinian territories), at Naghsh-e Rostam necropolis in Iran, at Myra in Lycia (today in Turkey), Nabataean tombs in Petra (modern Jordan) and Mada'in Saleh (Saudi Arabia), Sicily (Pantalica) and Larnaca. [2] Indian rock-cut architecture is very extensive, but does not feature tombs.