A civil union is a legally recognized arrangement similar to marriage, created primarily as a mean to provide recognition in law for same-sex couples. Civil unions grant some or all of the rights of marriage.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Belgium since 1 June 2003. A bill for the legalization of same-sex marriages was passed by the Senate on 28 November 2002, and by the Chamber of Representatives on 30 January 2003. King Albert II granted his assent, and the bill entered into force on 1 June. Polling indicates that a significant majority of Belgians support the legal recognition of same-sex marriage. Belgium was the second country in the world to legalise same-sex marriage, after the Netherlands.

The Civil Partnership Act 2004 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, introduced by the Labour government, which grants civil partnerships in the United Kingdom the rights and responsibilities very similar to those in civil marriage. Initially the Act permitted only same-sex couples to form civil partnerships. This was altered to include opposite-sex couples in 2019. Civil partners are entitled to the same property rights as married couples, the same exemption as married couples regarding social security and pension benefits, and also the ability to exercise parental responsibility for a partner's children, as well as responsibility for reasonable maintenance of one's partner and their children, tenancy rights, full life insurance recognition, next-of-kin rights in hospitals, and others. There is a formal process for dissolving civil partnerships, akin to divorce.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Ireland since 16 November 2015. A referendum on 22 May 2015 amended the Constitution of Ireland to provide that marriage is recognised irrespective of the sex of the partners. The measure was signed into law by the President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins, as the Thirty-fourth Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland on 29 August 2015. The Marriage Act 2015, passed by the Oireachtas on 22 October 2015 and signed into law by the Presidential Commission on 29 October 2015, gave legislative effect to the amendment. Same-sex marriages in Ireland began being recognised from 16 November 2015, and the first marriage ceremonies of same-sex couples in Ireland occurred the following day. Ireland was the eighteenth country in the world and the eleventh in Europe to allow same-sex couples to marry nationwide.

Same-sex marriage is legal in all parts of the United Kingdom. As marriage is a devolved legislative matter, different parts of the United Kingdom legalised at different times; it has been recognised and performed in England and Wales since March 2014, in Scotland since December 2014, and in Northern Ireland since January 2020. Civil partnerships, which offer most, but not all, of the rights and benefits of marriage, have been recognised since 2005. The United Kingdom was the 27th country in the world and the sixteenth in Europe to allow same-sex couples to marry nationwide. Polling suggests that a majority of British people support the legal recognition of same-sex marriage.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Greece since 16 February 2024. In July 2023, Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, head of the re-elected New Democracy party, announced his government's intention to legalise same-sex marriage. Its legalisation was part of an action plan for LGBT equality, which was drafted by a special committee appointed by Mitsotakis in 2021. Legislation was introduced to the Hellenic Parliament on 1 February 2024 and passed on 15 February by 176 votes to 76. The bill was signed into law by President Katerina Sakellaropoulou and took effect upon publication in the Government Gazette on 16 February. Polling suggests that a majority of Greeks support the legal recognition of same-sex marriage. Greece was the 16th member state of the European Union, the 21st country in Europe, and the 36th in the world to allow same-sex couples to marry.

Italy has recognised civil unions since 5 June 2016, providing same-sex couples with most of the legal protections, benefits and rights of marriage. A bill to this effect was approved by the Senate on 25 February 2016 and by the Chamber of Deputies on 11 May. It was signed into law by President Sergio Mattarella on 20 May, published in the Gazzetta Ufficiale the next day and took effect on 5 June 2016. The law does not grant same-sex couples joint adoption rights or access to in vitro fertilisation. Before this, several regions had supported a national law on civil unions and some municipalities passed laws providing for civil unions, though the rights conferred by these unions varied from place to place.

This article contains a timeline of significant events regarding same-sex marriage and legal recognition of same-sex couples worldwide. It begins with the history of same-sex unions during ancient times, which consisted of unions ranging from informal and temporary relationships to highly ritualized unions, and continues to modern-day state-recognized same-sex marriage. Events concerning same-sex marriages becoming legal in a country or in a country's state are listed in bold.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in New Zealand since 19 August 2013. A bill for legalisation was passed by the House of Representatives on 17 April 2013 by 77 votes to 44 and received royal assent on 19 April. It entered into force on 19 August, to allow time for the Department of Internal Affairs to make the necessary changes for marriage licensing and related documentation. New Zealand was the first country in Oceania, the fourth in the Southern Hemisphere, and the fifteenth in the world to allow same-sex couples to marry. Civil unions have also been available for both same-sex and opposite-sex couples since 2005.

Lithuania does not recognise same-sex marriages or civil unions. A bill to legalise civil unions and grant same-sex couples some legal rights and benefits is pending in the Seimas. Lithuania is the only Baltic state to not recognise same-sex couples in any form. Additionally, the Constitution of Lithuania explicitly prohibits the recognition of same-sex marriages.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Estonia since 1 January 2024. The government elected in the March 2023 election, led by Prime Minister Kaja Kallas and consisting of the Reform Party, the Social Democrats and Estonia 200, vowed to legalize same-sex marriage. Legislation to open marriage to same-sex couples was introduced to the Riigikogu in May 2023, and was approved in a final reading by 55 votes to 34 on 20 June. It was signed into law by President Alar Karis on 27 June, and took effect on 1 January 2024. Estonia was the first Baltic state, the first post-Soviet state, the twentieth country in Europe, and the 35th in the world to legalise same-sex marriage.

The legal status of same-sex marriage has changed in recent years in numerous jurisdictions around the world. The current trends and consensus of political authorities and religions throughout the world are summarized in this article.

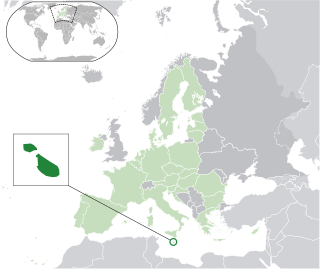

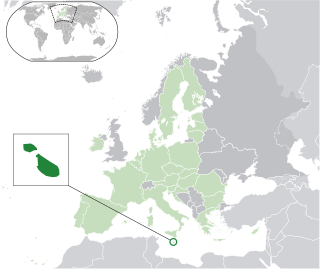

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) rights in Malta rank among the highest in the world. Throughout the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the rights of the LGBTQ community received more awareness and same-sex sexual activity was legalized on 29 January 1973. The prohibition was already dormant by the 1890s.

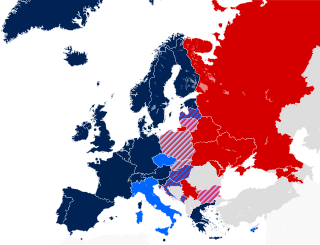

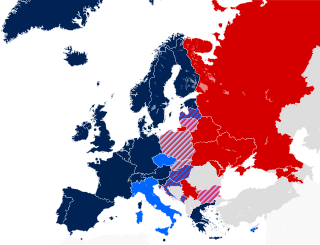

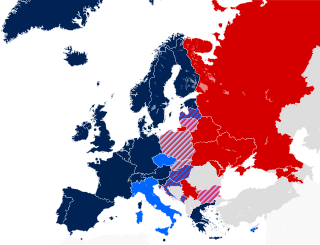

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) rights are widely diverse in Europe per country. 22 of the 38 countries that have legalised same-sex marriage worldwide are situated in Europe. A further 11 European countries have legalised civil unions or other forms of recognition for same-sex couples.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Northern Ireland since 13 January 2020, following the enactment of the Northern Ireland Act 2019. The first marriage ceremony took place on 11 February 2020. Civil partnerships have also been available for same-sex couples in Northern Ireland since their introduction by the Government of the United Kingdom in 2005.

Debate has occurred throughout Europe over proposals to legalise same-sex marriage as well as same-sex civil unions. Currently 33 of the 50 countries and the 8 dependent territories in Europe recognise some type of same-sex union, among them most members of the European Union (24/27). Nearly 43% of the European population lives in jurisdictions where same-sex marriage is legal.

Cyprus has recognised same-sex civil unions since 9 December 2015. Legislation to establish a form of partnership known as civil cohabitation was introduced by the ruling Democratic Rally party in July 2015, and approved by the Cypriot Parliament in a 39–12 vote on 26 November 2015. It was signed by President Nicos Anastasiades, and took effect on 9 December upon publication in the government gazette.

Same-sex marriage is legal in the following countries: Andorra, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Denmark, Ecuador, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Uruguay.

This is a list of notable events in LGBTQ rights that took place in the 2010s.

MGRM: The Malta LGBTIQ Rights Movement, previously known as the Malta Gay Rights Movement, is an LGBTQ rights organisation in Malta. It advocates for equality of all people regardless of sexual orientation, gender identity, sex characteristics and expression.