A civil union is a legally recognized arrangement similar to marriage, created primarily as a mean to provide recognition in law for same-sex couples. Civil unions grant some or all of the rights of marriage.

A domestic partnership is an intimate relationship between people, usually couples, who live together and share a common domestic life but who are not married. People in domestic partnerships receive legal benefits that guarantee right of survivorship, hospital visitation, and other rights.

The Civil Partnership Act 2004 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, introduced by the Labour government, which grants civil partnerships in the United Kingdom the rights and responsibilities very similar to those in civil marriage. Initially the Act permitted only same-sex couples to form civil partnerships. This was altered to include opposite-sex couples in 2019. Civil partners are entitled to the same property rights as married couples, the same exemption as married couples regarding social security and pension benefits, and also the ability to exercise parental responsibility for a partner's children, as well as responsibility for reasonable maintenance of one's partner and their children, tenancy rights, full life insurance recognition, next-of-kin rights in hospitals, and others. There is a formal process for dissolving civil partnerships, akin to divorce.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Ireland since 16 November 2015. A referendum on 22 May 2015 amended the Constitution of Ireland to provide that marriage is recognised irrespective of the sex of the partners. The measure was signed into law by the President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins, as the Thirty-fourth Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland on 29 August 2015. The Marriage Act 2015, passed by the Oireachtas on 22 October 2015 and signed into law by the Presidential Commission on 29 October 2015, gave legislative effect to the amendment. Same-sex marriages in Ireland began being recognised from 16 November 2015, and the first marriage ceremonies of same-sex couples in Ireland occurred the following day. Ireland was the eighteenth country in the world and the eleventh in Europe to allow same-sex couples to marry nationwide.

Same-sex marriage is legal in all parts of the United Kingdom. As marriage is a devolved legislative matter, different parts of the United Kingdom legalised at different times; it has been recognised and performed in England and Wales since March 2014, in Scotland since December 2014, and in Northern Ireland since January 2020. Civil partnerships, which offer most, but not all, of the rights and benefits of marriage, have been recognised since 2005. The United Kingdom was the 27th country in the world and the sixteenth in Europe to allow same-sex couples to marry nationwide. Polling suggests that a majority of British people support the legal recognition of same-sex marriage.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Denmark since 15 June 2012. A bill for the legalization of same-sex marriages was introduced by the Thorning-Schmidt I Cabinet, and approved by the Folketing on 7 June 2012. It received royal assent by Queen Margrethe II on 12 June and took effect three days later. Polling indicates that a significant majority of Danes support the legal recognition of same-sex marriage. Denmark was the fourth Nordic country, after Norway, Sweden and Iceland, the eighth in Europe and the eleventh in the world to legalize same-sex marriage. It was the first country in the world to enact registered partnerships, which provided same-sex couples with almost all of the rights and benefits of marriage, in 1989.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in the District of Columbia since March 3, 2010. On December 18, 2009, Mayor Adrian Fenty signed a bill passed by the D.C. Council on December 15 legalizing same-sex marriage. Following the signing, the measure entered a mandatory congressional review of 30 work days. Marriage licenses became available on March 3, and marriages began on March 9, 2010. The District of Columbia was the first jurisdiction in the United States below the Mason–Dixon line to allow same-sex couples to marry.

This article contains a timeline of significant events regarding same-sex marriage and legal recognition of same-sex couples worldwide. It begins with the history of same-sex unions during ancient times, which consisted of unions ranging from informal and temporary relationships to highly ritualized unions, and continues to modern-day state-recognized same-sex marriage. Events concerning same-sex marriages becoming legal in a country or in a country's state are listed in bold.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) rights in the Republic of Ireland are regarded as some of the most progressive in Europe and the world. Ireland is notable for its transformation from a country holding overwhelmingly conservative attitudes toward LGBTQ issues, in part due to the opposition by the Roman Catholic Church, to one holding overwhelmingly liberal views in the space of a generation. In May 2015, Ireland became the first country to legalise same-sex marriage on a national level by popular vote. The New York Times declared that the result put Ireland at the "vanguard of social change". Since July 2015, transgender people in Ireland can self-declare their gender for the purpose of updating passports, driving licences, obtaining new birth certificates, and getting married. Both male and female expressions of homosexuality were decriminalised in 1993, and most forms of discrimination based on sexual orientation are now outlawed. Ireland also forbids incitement to hatred based on sexual orientation. Article 41 of the Constitution of Ireland explicitly protects the right to marriage irrespective of sex.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) rights in Iceland rank among the highest in the world. Icelandic culture is generally tolerant towards homosexuality and transgender individuals, and Reykjavík has a visible LGBT community. Iceland ranked first on the Equaldex Equality Index in 2023, and second after Malta according to ILGA-Europe's 2024 LGBT rights ranking, indicating it is one of the safest nations for LGBT people in Europe. Conversion therapy in Iceland has been illegal since 2023.

The legal status of same-sex marriage has changed in recent years in numerous jurisdictions around the world. The current trends and consensus of political authorities and religions throughout the world are summarized in this article.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Sweden since 1 May 2009 following the adoption of a gender-neutral marriage law by the Riksdag on 1 April 2009. Polling indicates that an overwhelming majority of Swedes support the legal recognition of same-sex marriage. Sweden was the second Scandinavian country, the fifth in Europe and the seventh in the world to open marriage to same-sex couples nationwide. Existing registered partnerships remain in force and can be converted to marriages if the partners so desire, either through a written application or through a formal ceremony. New registered partnerships are no longer able to be entered into and marriage is now the only legally recognized form of union for couples regardless of sex.

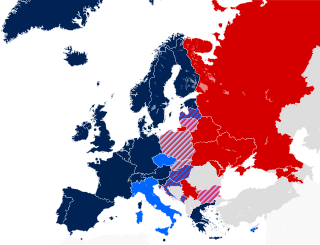

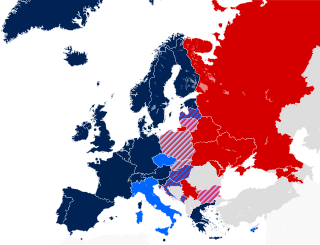

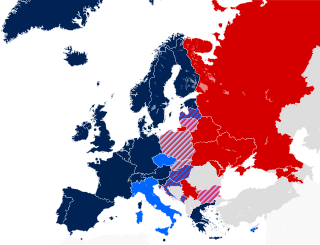

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) rights are widely diverse in Europe per country. 22 of the 38 countries that have legalised same-sex marriage worldwide are situated in Europe. A further 11 European countries have legalised civil unions or other forms of recognition for same-sex couples.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Norway since 1 January 2009 when a gender-neutral marriage law came into force after being passed by the Storting in June 2008. Norway was the first Scandinavian country, the fourth in Europe, and the sixth in the world to legalize same-sex marriage, after the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain, Canada and South Africa. Polling suggests that a majority of Norwegians support the legal recognition of same-sex marriage, and in 2024 Norway was named the best marriage destination for same-sex couples by a British wedding planning website.

This is a list of notable events in the history of LGBTQ rights that took place in the year 2009.

Debate has occurred throughout Europe over proposals to legalise same-sex marriage as well as same-sex civil unions. Currently 33 of the 50 countries and the 8 dependent territories in Europe recognise some type of same-sex union, among them most members of the European Union (24/27). Nearly 43% of the European population lives in jurisdictions where same-sex marriage is legal.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Malta since 1 September 2017 following the passage of legislation in the Parliament on 12 July 2017. The bill was signed into law by President Marie-Louise Coleiro Preca on 1 August 2017. On 25 August 2017, the Minister for Equality, Helena Dalli, issued a legal notice to commence the law on 1 September. Malta was the first European microstate, the 21st country in the world and the thirteenth in Europe to allow same-sex couples to marry nationwide. In 2024, Malta was named one of the best marriage destinations for same-sex couples by a British wedding planning website, and polling suggests that a majority of Maltese people support the legal recognition of same-sex marriage.

Same-sex marriage is legal in the following countries: Andorra, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Denmark, Ecuador, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Uruguay.

This is a list of notable events in the history of LGBTQ rights that took place in the year 2010.

This is a list of notable events in LGBTQ rights that took place in the 2010s.