Related Research Articles

In Norse mythology, Gná is a goddess who runs errands in other worlds for the goddess Frigg and rides the flying, sea-treading horse Hófvarpnir. Gná and Hófvarpnir are attested in the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. Scholarly theories have been proposed about Gná as a "goddess of fullness" and as potentially cognate to Fama from Roman mythology. Hófvarpnir and the eight-legged steed Sleipnir have been cited examples of transcendent horses in Norse mythology.

Ēostre is a West Germanic spring goddess. The name is reflected in Old English: *Ēastre, Old High German: *Ôstara, and Old Saxon: *Āsteron. By way of the Germanic month bearing her name, she is the namesake of the festival of Easter in some languages. The Old English deity Ēostre is attested solely by Bede in his 8th-century work The Reckoning of Time, where Bede states that during Ēosturmōnaþ, pagan Anglo-Saxons had held feasts in Ēostre's honour, but that this tradition had died out by his time, replaced by the Christian Paschal month, a celebration of the resurrection of Jesus.

In Norse mythology, Óðr or Óð, sometimes anglicized as Odr or Od, is a figure associated with the major goddess Freyja. The Prose Edda and Heimskringla, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson, both describe Óðr as Freyja's husband and father of her daughter Hnoss. Heimskringla adds that the couple produced another daughter, Gersemi. A number of theories have been proposed about Óðr, generally that he is a hypostasis of the deity Odin due to their similarities.

An Irminsul was a sacred, pillar-like object attested as playing an important role in the Germanic paganism of the Saxons. Medieval sources describe how an Irminsul was destroyed by Charlemagne during the Saxon Wars. A church was erected on its place in 783 and blessed by Pope Leo III. Sacred trees and sacred groves were widely venerated by the Germanic peoples, and the oldest chronicle describing an Irminsul refers to it as a tree trunk erected in the open air.

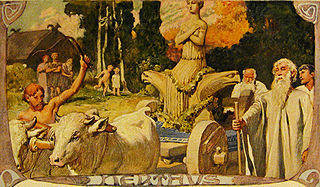

In Germanic paganism, Nerthus is a goddess associated with a ceremonial wagon procession. Nerthus is attested by first century A.D. Roman historian Tacitus in his ethnographic work Germania as a "Mother Earth".

According to Tacitus's Germania, Tuisto is the legendary divine ancestor of the Germanic peoples. The figure remains the subject of some scholarly discussion, largely focused upon etymological connections and comparisons to figures in later Germanic mythology.

Mannus, according to the Roman writer Tacitus, was a figure in the creation myths of the Germanic tribes. Tacitus is the only source of these myths.

In Norse mythology, Borr or Burr was the son of Búri. Borr was the husband of Bestla and the father of Odin, Vili and Vé. Borr receives mention in a poem in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional material, and in the Prose Edda, composed in the 13th century by Icelander Snorri Sturluson. Scholars have proposed a variety of theories about the figure.

Germanic paganism or Germanic religion refers to the traditional, culturally significant religion of the Germanic peoples. With a chronological range of at least one thousand years in an area covering Scandinavia, the British Isles, modern Germany, Netherlands, and at times other parts of Europe, the beliefs and practices of Germanic paganism varied. Scholars typically assume some degree of continuity between Roman-era beliefs and those found in Norse paganism, as well as between Germanic religion and reconstructed Indo-European religion and post-conversion folklore, though the precise degree and details of this continuity are subjects of debate. Germanic religion was influenced by neighboring cultures, including that of the Celts, the Romans, and, later, by the Christian religion. Very few sources exist that were written by pagan adherents themselves; instead, most were written by outsiders and can thus present problems for reconstructing authentic Germanic beliefs and practices.

The Marsi were a small Germanic tribe settled between the Rhine, Ruhr and Lippe rivers in northwest Germany. It has been suggested that they were a part of the Sugambri who managed to stay east of the Rhine after most Sugambri had been moved from this area. Strabo describes the Marsi as an example of a Germanic tribe who were originally from the Rhine area, now the war-torn Roman frontier, but had migrated deep into Germania.

In Germanic mythology, Seaxnēat or Saxnôt was the national god of the Saxons. He is sometimes identified with either Tīwaz or Fraujaz.

In Tacitus' work Germania from the year 98, regnator omnium deus was a deity worshipped by the Semnones tribe in a sacred grove. Comparisons have been made between this reference and the poem Helgakviða Hundingsbana II, recorded in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources.

The Alcis or Alci were a pair of divine young brothers worshipped by the Naharvali, an ancient Germanic tribe from Central Europe. The Alcis are solely attested by Roman historian and senator Tacitus in his ethnography Germania, written around 98 AD.

Zisa or Cisa is purportedly a pagan goddess once worshipped in Augsburg. Some modern scholars consider the goddess to have been an innovation of the post-medieval period.

In Germanic paganism, Baduhenna is a goddess. Baduhenna is solely attested in Tacitus's Annals where Tacitus records that a sacred grove in ancient Frisia was dedicated to her, and that near this grove 900 Roman soldiers were killed in 28 CE. Scholars have analyzed the name of the goddess and linked the figure to the Germanic Matres and Matronae.

In Germanic mythology, an idis is a divine female being. Idis is cognate to Old High German itis and Old English ides, meaning 'well-respected and dignified woman.' Connections have been assumed or theorized between the idisi and the North Germanic dísir; female beings associated with fate, as well as the amended place name Idistaviso.

In Roman historian Tacitus's first century CE book Germania, Tacitus describes the veneration of what he deems as an "Isis" of the Suebi. Due to Tacitus's usage of interpretatio romana elsewhere in the text, his admitted uncertainty, and his reasoning for referring to the veneration of an Egyptian goddess by the Suebi—a group of Germanic peoples—scholars have generally held that Tacitus's identification is incorrect, and have debated what goddess Tacitus refers to.

In Norse mythology, the sister-wife of Njörðr is the unnamed wife and sister of the god Njörðr, with whom he is described as having had the twin children Freyr and Freyja. This shadowy goddess is attested to in the Poetic Edda poem Lokasenna, recorded in the 13th century by an unknown source, and the Heimskringla book Ynglinga saga, a euhemerized account of the Norse gods composed by Snorri Sturluson also in the 13th century but based on earlier traditional material. The figure receives no further mention in Old Norse texts.

Trees hold a particular role in Germanic paganism and Germanic mythology, both as individuals and in groups. The central role of trees in Germanic religion is noted in the earliest written reports about the Germanic peoples, with the Roman historian Tacitus stating that Germanic cult practices took place exclusively in groves rather than temples. Scholars consider that reverence for and rites performed at individual trees are derived from the mythological role of the world tree, Yggdrasil; onomastic and some historical evidence also connects individual deities to both groves and individual trees. After Christianisation, trees continue to play a significant role in the folk beliefs of the Germanic peoples.

References

- Church, Alfred John. Brodribb, William Jackson (Trans.) (1876). Annals of Tacitus. MacMillan and Co.

- Frost, Percival (1872). The Annals of Tacitus. Whittaker & Co.

- Simek, Rudolf (2001 [1993]). Dictionary of Northern Mythology. D. S. Brewer.